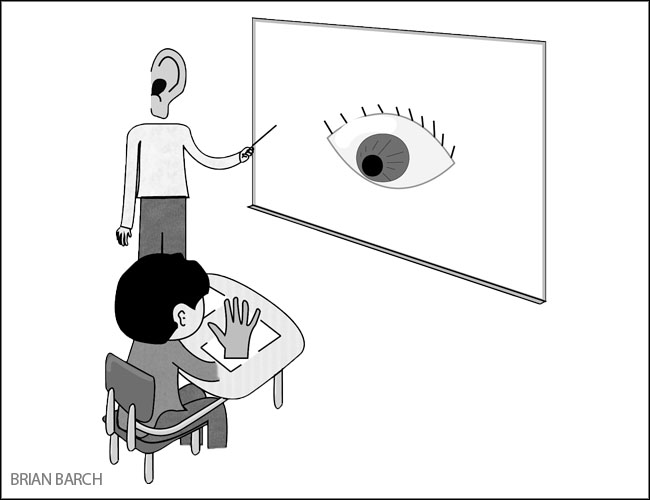

Over the past generation, many high schools have transformed learning from a full day of lecture into a mixture of note-taking, interactive tasks, and simulations. The concept of learning styles played a large role in this shift in teaching technique. Varying from kinesthetic to visual, the learning styles designate each individual as learning most effectively when taught through a certain approach. But is this concept truly valuable or insignificant?

In their article, The Myth of Learning Styles, psychologists Cedar Reiner and Daniel Willingham investigate the learning styles, separating truth from exaggeration. They begin by presenting the aspects of the theory that studies have deemed true.

For one, they explain that the way each individual learns differs from one person to the next and influences efficiency. Background knowledge also affects learning by improving one’s ability to grasp concepts that are familiar. Additionally, learning varies based on subject matter and individual learning capacities. Taking this into account, many of the teachers at Aragon present lessons in ways that address the abilities—not necessarily the learning styles—of different students.

English teacher Holly Dietz says, “Mostly it’s intuitive and based on the needs that I see out there. I don’t know if [students] fall so neatly into the categories, but I think it’s very natural as an observer of students over the years to think that there are types— that I’m going to be able to reach this [student] this way.” Senior Ivan Wang adds, “Teachers don’t explicitly state that they’re using [the learning styles], but I guess it manifests in things like powerpoints and movies.”

Next, Reiner and Willingham cover the controversial aspects of the concept. One example is the idea that regardless of the content taught and individual capabilities, presenting information through one’s preferred method enhances their learning. Another point of criticism is the biological basis behind the theory which says that the learning styles operate from within the brain. As of now, little evidence exists to support these claims. Dietz adds, “If this is a theory you’re going to depend on, it’s hard to address all [of the learning styles] to the level that you want for all the kids in the room.”

Freshman Jake Huth adds to the flaws, “I took a quiz to see what kind of learner I am, but I got equal amounts [of points] in each category.” “I mean if it exists as it’s described that’s great, it’s helpful knowledge to know, but I guess I’m dubious about that being sort of the only thing that’s holding the kid back,” says Dietz.

She adds, “Everything that I’ve seen in students shows me that there are such things as different learning styles. I know that if I sit down with a student and one way that I try to get a message across doesn’t work, a lot of times if I try something else it does work.” Junior Thomas Bebbington reasons, “Despite the fact that I can read things several times and learn from them, I won’t learn as much as [I would have] if I had actually participated in something or visualized it by seeing a drawing.”

In conclusion, while students have learning preferences, they do not necessarily cause the students to learn better. However, each student’s unique skills, as well as their past awareness and subject matter, affects how they learn. Additionally, while lesson plans targeted at specific learning styles are impractical, the theory has encouraged teachers to produce lesson plans that present information in a variety of ways. While this may not target each individual’s learning style, it does serve to make lessons more enticing.