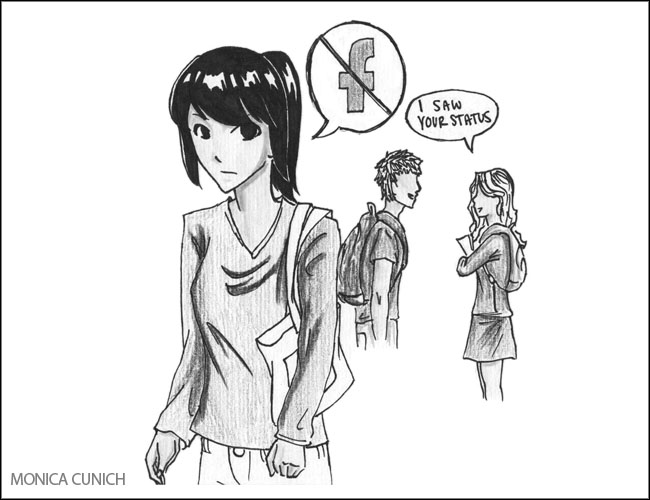

As Facebook surfaces as one of the most popular websites with more than 800 million active users, it seems as though every teen has an account. 80 percent of teens who go online use social networking sites, but this leaves a full 20 percent of online teens who do not participate.

Psychologist Larry D. Rosen, a professor of psychology at California State University, stated, “Facebook can be distracting… Studies found that middle school, high school, and college students who checked Facebook at least once during a 15-minute study period achieved lower grades.”

Rosen claims, “daily overuse of media and technology has a negative effect on the health of all children, preteens and teenagers by making them more prone to anxiety, depression, and… narcissistic tendencies.” The rare teen without a Facebook may even agree.

Aragon senior Kathryn Miyahira attributes her lack of a Facebook account to many similar reasons. “At first, my parents didn’t want me to have one, and over time it just seemed unnecessary. I do believe [having a Facebook] would be a distraction. Many people come to school saying that they went to bed at three in the morning, and when I ask why, they reply that they were on Facebook. They made the decision to stay up on Facebook instead of sleep.”

Whether it is a personal concern or not, most teens are aware that Facebook can become a platform for procrastination. Junior Carly Olson, who only recently joined Facebook, has found her own way to deal with the reluctant addiction. She says, “I downloaded an application on my computer called Self Control, which allows me to block certain websites for as long as I want. If I’m way too distracted, I can use that to help.”

However, some maintain that there are other side effects that cannot be avoided. Senior Suzy Swartz, who does not currently have a Facebook account, says, “I did have one for a few months when I was a sophomore because my friends had been pestering me for so long about it. Then, when I was on the website, I realized that all of those bad things that I’d thought about Facebook were true; it’s sort of disingenuous, distracting, and makes [people] act like narcissistic jerks.”

She adds, “For instance, I wouldn’t care if Barack Obama had just eaten a ham sandwich—why would I care if some kid in one of my classes had just had one? It’s the closest thing to ‘important’ and ‘celebrity’ that we will ever feel as teenagers, so I guess that’s the appeal.”

Because these “narcissistic tendencies” may be more common on a social networking site than during a live interaction, Facebook can be seen as an obstacle to authentic friendship.

Swartz says, “I hate the idea of a person’s life being condensed into a web page. It boxes you in and makes you a caricature of your real self.”

However, Facebook can have its advantages. Rosen has found that “social networking can provide tools for teaching in compelling ways that engage young students,” and many Aragon students agree.

Swartz admits, “It has its perks. I think it’s convenient that you can quickly get a school question out to hundreds of people who can help you out which you couldn’t do without a Facebook.”

Its community of fellow students isn’t the only benefit of Facebook.

Olson recounts why she first joined, saying, “Over the summer, I went to a camp in Massachusetts and met a lot of new friends from all over the country. Facebook seemed like the best way to keep in touch.”

Miyahira, who does not currently have an account, adds, “I do plan on getting a Facebook when I go away to college because then I really won’t be able to see my friends and I can at least be updated on what they may be doing.”

Students approach Facebook in many different ways. Some are addicted, others use it sparingly, and many sign up with caution. With the new conflicts of the media age, learning when to use Facebook and when to set it aside may be a test to the future of social interaction.