In an attempt to boost the national ranking of her college, an administrator at top liberal arts college Claremont McKenna reported falsely high SAT scores to U.S News & World Report. Though many colleges have previously tried fudging their rankings in the past, Claremont McKenna is the highest ranked college to have been exposed doing so.

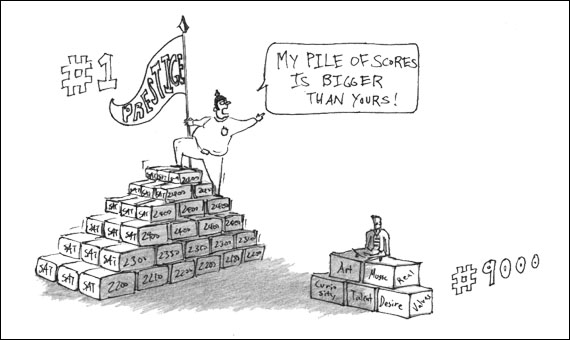

In turn, this brings further attention to the college rankings themselves. How are colleges ranked and do rankings really matter to a point in which admissions officers must resort to unethical reporting methods?

The U.S. News National College Ranking weights specific criteria in determining rank. Undergraduate academic reputation alone comprises of 22.5 percent of the formula for rank, retention and faculty resources each comprise 20 percent and student selectivity alone comprises a mere 15 percent. SAT and ACT scores are half of student selectivity, making up 7.5 percent in the overall scoring criteria.

Because the formula for rank is more or less concrete, various colleges over the years have been publicly exposed in manipulating reported data in hopes of a higher rank. According to “Gaming the College Rankings,” an article published in The New York Times, Baylor University offered financial rewards for admitted students to retake the SAT and Iona College admitted towards lying about a myriad of criteria reported for ranking.

Various methods of improving rank other than inflating SAT scores have surfaced throughout the years. “Tufts Syndrome,” is a rumored method in which colleges protect their yield, the amount of accepted students that actually attend, by rejecting overqualified applicants. Yet, in a Tufts sponsored admissions video, Tufts University senior assistant director of admissions Daniel Grayson denies the use of such methods.

To colleges, rank does indeed matter; slight increases in rank correlate with more applicants in the following fall semester. Economics reporter for the New York Times Catherine Rampell says, “The rankings matter more for universities, as opposed to liberal arts colleges, and more so for institutions ranked in the top 25 or that move from the second page of rankings to the first page of the magazine’s listing.”

Thus, it is clear that rank does produce tangible results for colleges; yet, does rank have a connection with the success of a student at a college? Aragon college and career advisor Laurie Tezak says, “Don’t pick a school because of name; pick a good fit. [Rank] is an issue if [it is] the only way a kid picks a school. Some schools pay to have [their] names in ranking; [it is] not entirely reliable.”

Many Aragon students reach a consensus that while rank is important, it is still only one of many pieces that factor in their choosing a university. Senior Kate Blood says, “It is a good indicator of how good it is [academically], but it is not how the school feels. For me it is not about the SAT scores but about the teachers, people, and campus there. [Rank] is not something someone should base [his or her] whole college experience on.”

Teacher Heather Sadlon says, “[Rank] has become an easy way for students to get a quick snapshot view. [It has] received too much emphasis. Having gone to three universities that varied greatly in rank, I had similar experiences at all of them. There were professors I liked and did not like.”

Similarly, as to rank’s correlation with success in finding employment, students and teachers alike believe that while rank plays a role, the process of maturation through college is a much bigger factor. Tezak says, “I think it is what you learn from college, how you work with a group and your interviewing skills. It is what you got out of a school [that matters].”

In short, rank undeniably matters to both colleges and students as a factor of success. Yet, it is only one part of many pieces that factor into both a college’s reputation and a student’s success. Aragon alumnus Christopher Chu says, “Overall, regardless of rank, your future is in your hands.”