This past September, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill that will raise the minimum wage to $9 by July 2014 and $10 by Jan. 2016, making California’s minimum wage the highest in the nation. Outlook polls project that over half of Aragon’s employed upperclassmen are expected to see a pay raise due to this recent bill.

However, within the legislature and around the state, there has been a debate over this raise. This boost is expected to increase the yearly average income by $4,000, giving an extra $2.6 billion to those currently making minimum wage, according to John Perez, the Democratic Speaker of the California State Assembly, who worked to pass this bill. This recent increase is said to affect roughly 2.4 million people who currently work for minimum wage in the state.

Supporters argue that, given California’s high cost of living, the wage raise is a justified measure to improve the livelihoods of those at the bottom of the economic spectrum.

“I can’t imagine what it would be like to live off of, say, $7.25 an hour in the Bay Area,” says economics teacher Heather Sadlon. “Regardless of what the poverty line is, that’s such a horrible standard of living if you’re working 40 hours. You can’t afford child care, you can’t afford an apartment, you just can’t afford to live. That’s just from a moral point of view.”

They also note that increasing the wages of low income workers will stimulate consumer spending, thus fueling the state’s economy. Sadlon says, “If I don’t have money in my pocket as a worker, I can’t spend money. And from an economics point, people need to spend money.”

However, opponents contend that this measure will actually hurt those it intends to help by increasing unemployment. Jennifer Barrera, who works as a policy advocate at the California Chamber of Commerce, one of the business groups opposing this measure, states, “We have it tagged as a job killer, given the increased costs businesses will be faced with.”

Sadlon, though generally supportive of the measure, adds, “If you look at it from an economic point for businesses, you’re basically creating a surplus of workers. Eventually, if you keep raising the minimum, it technically leads to unemployment, because [businesses] won’t hire people. You’ll find another way to do it because it’s just not viable.”

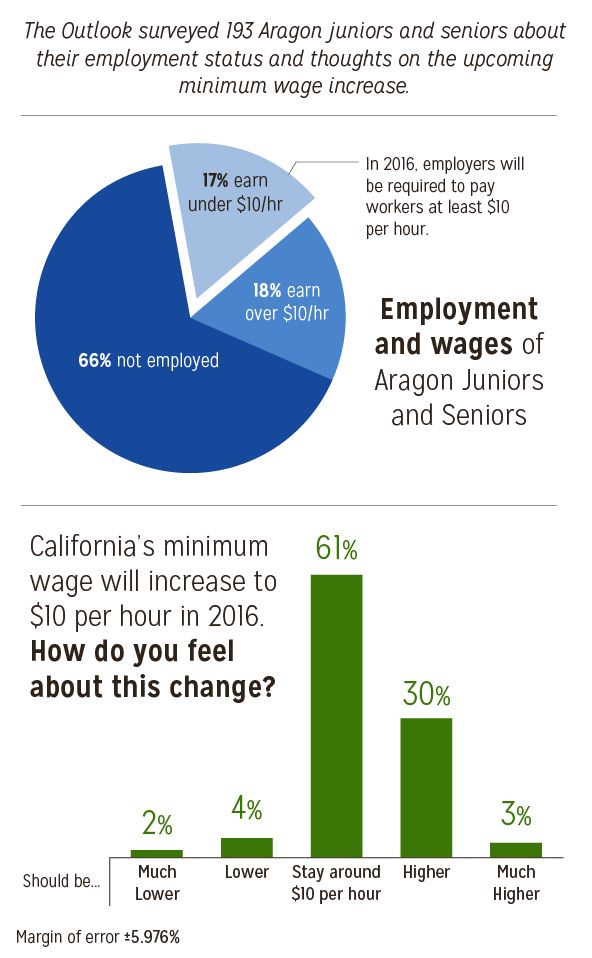

Overall, Aragon students have supported this recent measure. In a poll of juniors and seniors, 94 percent of respondents thought that the new minimum wage of $10 an hour was either just the right amount or too low, while roughly six percent responded that the measure brought the wage too high.

This change comes as Aragon is experiencing heightened student employment, due to the end of the recent recession. Counselor Laurie Tezak explains that, although employers have been hesitant to hire students in recent years, more opportunities have recently re-emerged.

She says, “We’ve seen a big number of employers coming to us again. I think it might be harder for students to continue to find jobs with such an increase, but there are places that tend to want a younger person. We’re still going to see jobs, however. I don’t think the increase will stop the job flow.”

The same poll of upperclassmen showed that roughly 34 percent are currently working a paid position, and that roughly 52 percent are currently paid under 10 dollars per hour; if that percentage stays constant over the next three years, then over half of Aragon students currently employed will experience a pay raise as per the recent law.

Junior Colin Harrington, who is employed, concludes, “It’s exponentially better in the long run. I don’t think [its effect] to be overlooked, even on a small scale like Aragon. I think it’ll make a big difference to those who are employed.”