Last March, junior Stephanie Mao started an online drivers’ education course at home. “I started, but I never finished. The whole process was ridiculous,” she says. “I got past the ‘History of the Automobile’ portion and I was like, ‘Are you joking?’ It said stuff about the statistics of cars in the 1920s, and when I actually got to the driving part, I said, ‘I’m done.’”

Mao’s disenchantment with the drivers’ education process is not unusual for her generation. Today, fewer young people are motivated to obtain a license. According to a 2011 study at the University of Michigan, around half of eligible 16-year-olds had licenses in 1983. In 2014, that number is estimated to be 25 percent. USA Today published a poll last December about the decline. According to the poll, “being too busy” or “not having enough time” is the number one reason teens choose to delay the decision to drive. Other top reasons include the costly price of car ownership and easy access to transportation from others.

As the number of young drivers drops, signs point to a decreasing social value of car ownership. Senior Darrell Ten says, “Personally, I would rather have a new iPhone than a new car. With a phone, you can look at directions and call people to ask for a ride. It’s more convenient, too, and it requires less maintenance and fewer payments.”

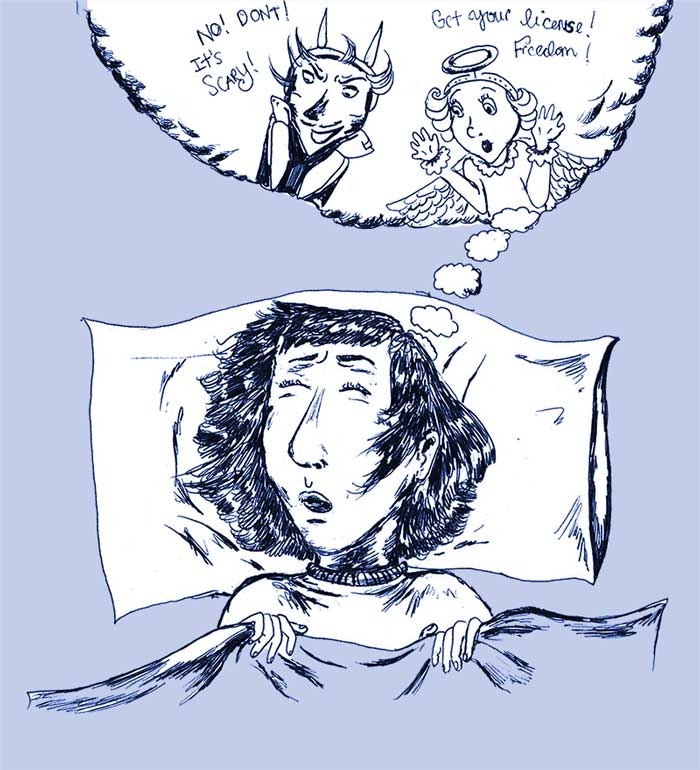

Aragon parent Christine Huth recounts the significance of getting a license when she was a teenager. “Driving meant being able to go where you wanted to go,” she says. “It meant freedom.”

Science teacher Kevin Doyle says, “I grew up in a semi-rural area and nobody lived close to anybody. You needed a car to get from here to there. I lived eight miles from school.” He adds, “Cars were a big part of our lives, and they were a lot easier to work on then. It was common for dads and sons to get together and work on an old car to get it running. You could do that back then.”

However, in a modern world where 52 percent of Americans use social networking and 35 million take public transportation daily, American driving culture has already peaked, and some claim that it will only continue to decline.

In fact, a recent article from National Geographic News notes that the decreasing number of teen drivers is inversely proportional to the number of young internet users. The article attributes constant social connectivity to a lack of motivation to drive.

Inside schools, drivers’ education programs have largely disappeared, often being replaced by private classes or online services. Doyle says, “When I first started teaching at Aragon, driving classes were mandatory, everybody had to take it. We also had an autoshop at the time.”

Huth laments the loss of such programs. “It’s a shame that there [are fewer] of those programs,” she says. “You would sign up for the class, learn about all the rules, and practice for the written test at the DMV. At the end you would also go out and practice in a real car.”

While public school programs are cut, teenage driving laws have become stricter as well. Current California laws state that drivers under the age of 18 cannot transport other teenagers during the first year of their license. The law is meant to curb distractions within the car.

“Teenagers have a sense of immortality,” says Doyle. “Driving stupid can be fun, but sometimes fun trumps sensibility—particularly in teenagers. I think anything that can be done to mediate the potential is a good thing.”

With increasing limits, teenagers turn to alternatives instead of pursuing a license. Mao says, “I feel like we’re depending on each other a lot more nowadays than in the past. When we have rides from our family or friends, we don’t feel as motivated to get our own license. It’s easier to beg for rides or ask our family or friends.”

Senior Ria Patel outlines the benefits of convenient driving alternatives. “If I want to go to a concert in the city I can use BART or Caltrain for that because parking is crazy. Last summer my friends and I went to SAP Center in San Jose. Caltrain stops literally right in front of it.”

Doyle supports more public transportation for the 21st century. “In urban areas, I hope that there’s an increasing trend against driving vehicles. If we, in this country, can get public transportation efficient enough and running through more places, that lack of dependence on cars would be a good thing. As for rural areas, people are still going to be in cars.”

Despite living in surburban San Mateo, junior Jake Huth decided to get his license. He believes his parents were the primary influence. “My parents used to drive me everywhere. It makes sense that they encouraged me to get a license. It was inconvenient for them.”

Jake Huth’s father, William Huth, comments on his role in Jake’s decision to get a license. “It’s not necessarily that he inconvenienced us; we wanted Jake to get a license more as a developmental step, a rite of passage. That’s what it always meant for us.”