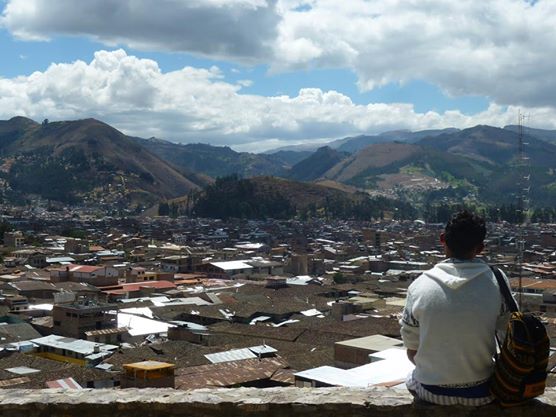

In a rusty schoolhouse in Peru’s Cajamarca Province, junior Scott Chow lines up a class of elementary school students in a game of “Red Light, Green Light” as part of an after-school academic enrichment camp or campamento. The students excitedly surge forward at each command and curiously watch as Chow places stools and desks in the pathway. As the game progresses, the students inch forward and finally, the first student makes it across the line. Speaking in Spanish, Chow makes a connection between the difficulties maneuvering through obstacles in the game and fire safety.

This past summer, Chow and junior Kate Holland guided activities like this during their trips with Amigos de Las Americas. After receiving training, they led community-based initiatives focused on public health and environmental sustainability, created curriculum for campamento, lived with host families, experienced cultural immersion and practiced Spanish. Each student was placed in a different community located in Cajamarca.

Holland’s group led an initiative to help the agricultural community by purchasing sheep. Although Holland’s group followed cultural norms, they faced challenges in gaining support from Peruvians who felt wary following alleged reports of organ harvesters associated with the western world.

“Our project wasn’t big, but it was really hard for us to get community support for the project. The people who we knew well were interested in our project, but there were many people who were skeptical of Americans,” says Holland.

Going to field after field, Holland’s group invited community members to join meetings to discuss the initiative, but most of the time, the people who had promised to attend failed to show up at the meeting.

“One big thing I learned was that relationships mattered. A lot of the people who we had close relationships with would show up. I didn’t realize at first, but that’s when I tried not just to advertize to the meeting. I learned to get close to the people and know them better and listen to them. I learned about their life and what they liked. I learned that is how you get more people involved and [get] the community vested with working with you,” says Holland.

In addition to leading initiatives, Amigos members teach campamentos based off unique Amigos de las Americas objectives. Chow, who taught both elementary and high school students, focused on public health and noted a significant difference between groups.

“The elementary students loved the campamentos, but the high school students were especially bored. They weren’t uninformed. I felt a bit angry we were doing it for them because they already knew it. It was a bit pretentious and rude for us to go in and do it,” says Chow.

Cultural immersion was another part of Amigos. As both students lived with host families, they say they instantly felt welcomed into a culture of hospitality and openness.

“I formed a strong relationship with my host mom. I got sick a lot, and she was always there to take care of me,” says Chow. “Once, I got sick before the festival, and at first, my host mom was not exactly prepared for it. I don’t know how, but she managed to juggle preparations, tasks, and taking care of me.”

Through this journey, both report learning more about themselves and society.

“It was life changing and defining. I realized that I want to become a teacher because of the intensive teaching there. It’s pretty fun to do, and it’s fantastic to try and think, ‘I can do this,’” says Chow.

Holland noted a change in her global perspective. After noticing drastic socioeconomic differences between wealthy tourists and her community members, Holland felt uncomfortable as she compared the luxuries to the minimal assets.

“I couldn’t criticize [the rich] because I’m the same way,” says Holland. “But people there have to come to terms with how people in this world live. [Americans] get to ignore that and in doing so, sometimes we forget that some of our problems don’t really matter, and there are things we could be doing that are more important.”

With new perspectives, both invite others to join Amigos.

“If you are willing to dive into a great adventure and take a risk and go to a completely different country for four to eight weeks without knowing the people you are going to be with, and you are willing to take that kind of risk, then Amigos is something for you,” says Holland.

At the conclusion of Amigos, Chow feels relieved and stronger. He says, “It was one of the hardest things I have ever done. It feels great to know I beat it—I did it.”