At Aragon, most of the novels read in English class are written by white and male authors. Certain novels like Beloved by Toni Morrison, To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee, and Frankenstein by Mary Shelley do provide some diversity in our curriculum, but is this enough? The Outlook editorial team presents a variety of perspectives on whether or not more diverse authors should be integrated into the curriculum, looking at the different obstacles presented by implementation, the true purpose of literature and how white and male voices are dominating our narratives.

Diversity will take time

Karan Nevatia, Features Editor

One look beyond Ms. Wang’s cluttered desk reveals her even messier bookshelf — the racks are littered with odd copies of old, tattered novels, a replica of Holden Caulfield’s red hunting hat, and, perhaps most importantly, large, 3-inch binders stuffed with papers struggling to escape the crowded folders. Each binder has a paper label on the spine. They read: Great Expectations, Catcher in the Rye, In Cold Blood. But one binder is noticeably thin — the label says My Antonia, and the papers inside are orderly and crisp.

That’s because Ms. Wang has been teaching classics written by household names like Dickens and Salinger for years, but only introduced My Antonia, a novel written by a female author, Willa Cather, this year. Granted, My Antonia is a summer reading novel, which may account for some of the smaller curriculum, but it mostly results from the difficulty of writing new lessons for the book.

Adding a novel to any English teacher’s curriculum takes a considerable amount of work — writing daily lessons, creating guiding questions for every chapter, and even making new vocabulary lists is tedious and seemingly unnecessary. Why waste time writing a new lesson for a new book when you could be improving the lessons for books you already have or helping struggling students understand the material?

New novels also erase any advanced experience that comes with teaching books already in the curriculum. Every time you read the same book, you gain a deeper understanding of the novel, and often find something new that you missed the first time around. Ms. Wang knows The Catcher in the Rye like the back of her hand. She can’t say the same about My Antonia.

Implementation into the classroom isn’t the only issue. The Aragon library needs to have enough copies of the book to lend out to students who might be unable to buy their own copies, creating another roadblock in bringing diversity to the English curriculum.

While integrating books written by underrepresented minorities into our English classes is a great idea, implementing new novels of any kind will take patience.

Diversity benefits all

Monica Mai, News Editor

Literature, without a doubt, shapes our primary worldviews and perspectives. It transports us to other worlds and experiences of other characters. It gives us insight into another character’s mind and provokes a sense of empathy between the reader and the character. It is an extremely powerful medium, capable of establishing what we know and understand about each other.

For minority students, they are often not represented in literature written by white, Anglo-Saxon males. In the books that I’ve read in my English classes, I don’t recall a single Hispanic or Asian character. In books like Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1984, and Brave New World, the female characters are usually portrayed as weaker and more submissive. We need to dispel these stereotypes by reading more multicultural books. It’s important to read books written by more authors of color so students of color can relate. Though the former and the latter don’t always exactly correlate, reading about people that look like them and share similar backgrounds allows them to discover their own identities and individuality. It also affirms that there are possibilities for people like them, that they, too, can be heroes and role models. This will promote self-acceptance and comfort in their own skin.

For the students who aren’t a minority, it’s important to them to broaden their perspectives and learn of different experiences. They go to school to grow and expand their consciousness, and it’s difficult to do so without breaking the barriers of difference. These students need to read about the endless narratives out there and listen to the voices of the minorities. This exposure is important because it reflects reality — everyone

Education includes teaching students their responsibilities as humans, and part of that is being empathetic and compassionate. We must be more inclusive in our reading so all students can expand in global consciousness. Diversifying the curriculum at Aragon will promote inclusivity and a greater understanding of the plight of others.

Good literature speaks across cultures

Janet Liu, Centerspread Editor

How many of us can’t laugh with the rambunctious Scout Finch when she spends a summer with Dill and Jem? How many of us don’t grimace as Jack and Ralph slowly become unhinged on a lonely desert island? Classic literature is full of references to the shared human experience — that’s what makes it timeless — and it’s simply untrue to claim that because we don’t wander the city streets, smoking and sending for prostitutes, we can’t feel and appreciate Holden’s sense of alienation. The characters, settings, and experiences through which a writer conveys her message are artistic choices. A good English class teaches us to look beyond the art and find, within, its jewel.

If the question of stifling perspectives is at stake, contextual analysis and cultural awareness are what should be added to the English curriculum. In AP English Literature and Composition, we temper our reading of Heart of Darkness with Chinua Achebe’s cultural criticism, but that doesn’t invalidate Joseph Conrad’s art. In fact, our reading of the text is richer for knowing where the art falls short, and treading the line between what was then considered acceptable and what is now considered acceptable improves our critical understanding of the world.

If Ayn Rand or Toni Morrison have conveyed particular emotions better than Salinger or DeLillo could, then there is every reason to change what we read; it is only a matter of time until we do. But in the meantime, I appreciate any author who can communicate an interesting idea with pure lyrical skill, and I’ll indulge in Amy Tan on my own time.

Strengthening the individual’s voice through mindful diversity

Virginia Hsiao, Features Editor

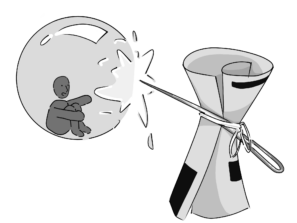

Sometimes while writing, a hypercritical version of Jiminy Cricket slowly takes over the usual commentary in my mind. Something seems off about this word choice. The readership might feel less convinced by this phrasing. After closer examination, I’ve come to realize that this non-Disney Jiminy Cricket is guided by what it perceives as good literature: the white and male voice.

While I do not deliberately attempt to emulate my favorite white Anglo Saxon male authors, and Jiminy’s suggestions do not always make it onto the page, my “Jiminy Cricket” has subtly learned to value the white and male voice as one of power and as the standard for “good” writing.

In her article “On Pandering,” Clare Vaye Watkins, author of the acclaimed novel Gold Fame Citrus, summed up this sentiment. “I thought of [male writers] as the standard bearers, and the types of writing that I had to aspire to, to be accepted. Whereas when I read someone like Toni Morrison … I wasn’t giving her voice the same authority and gravitas.”

When the majority of the novels presented in English classes come from a white and male voice, it becomes easy for students to subconsciously pick up the idea that the white and male voice is the ultimate standard for writing. While we have read novels like Beloved, which present strong voices from members of traditionally underrepresented populations, the comparatively low presentation of such novels makes it difficult for students to fully appreciate the value of voices for what they truly are: unique and powerful.

Instead, while the overarching narratives, which typically highlight the minority perspective, functionally allow for greater representation of the community, they create an expectation that the specific author somehow speaks for his or her subpopulation at large.

Because of this, the emphasis is no longer placed on the literary value but rather, on how well the author’s perspective represents the minority sentiment — no matter how universal “good” writing is. It’s not to say such a perspective is unimportant, but the perceived function, which ironically emphasizes the societal power structure, undermines the value and the power of the tone presented.

Greater diversification of authors presented within the curriculum will remedy this problem, as the acknowledgement of such pieces beyond their role as sole representatives of their minority subpopulations will make it easier for individuals to understand the strength of voices that do not fall within the archetype of the white and male voice. Hopefully, with these efforts, Jiminy Cricket’s view stays true to the individual and strengthens unique voices.