Michelle Carter was 21 years old and fresh out of journalism school when she first experienced gender inequality in the workplace. It was 1966, and she had been offered a job at the Kansas City Star, a newspaper in Missouri. “I accepted the offer,” says Carter. “And when I showed up … I was hired as copy editor. Well, they had never had a woman who was copy editor … the first thing they realized was that there was no vanity panel at the desks.” What exactly is a vanity panel? “A piece of plywood, essentially, that covered the front of my desk,” Carter describes. She was shocked. “In other words, they were concerned about people looking up my skirt. So, the first thing [they did], even before I could start to work, they got a carpenter in to put a vanity panel over my desk.”

Some of the barriers Carter faced were, in fact, physical barriers. However, she was not going to let them block her from taking on a leadership role; she saw an opportunity, and took it. Her boss did not want to spend his Saturday nights laying out the paper for the Sunday edition, and no one else was willing to stay either. Carter volunteered: “I said, ‘I think I can do that.’ … So, within a month, I was laying out the Sunday paper of a major metropolitan newspaper.”

This meant she was working alone until about 2 a.m. on Saturday nights. This worried the men she worked with. “They hired a copy boy whose only job was to walk me to my car at 2 a.m.,” says Carter. “They were willing for me to do the job [of laying out the paper], but wanted to be absolutely sure that I didn’t have [my safety] to worry about.”

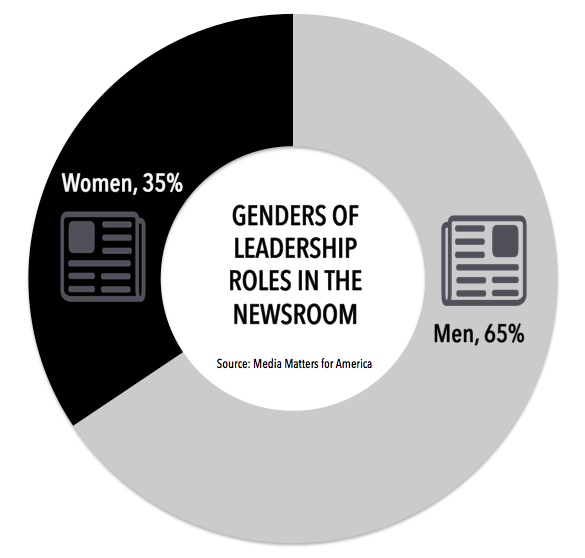

While this type of treatment may seem outdated, it is still very real. According to Think Press, a politics and news blog, nearly 30 percent of women have experienced discrimination in the workplace. And the journalism and news field is not much better. Media Matters for America released a study in 2013 that found that women made up only 38 percent of the newsroom staff — and that number had stayed the same for 14 years. The number of women in leadership roles in the newsroom is even lower, at 35 percent.

This underrepresentation is not just in the office, but in all aspects of the media. An annual report by the Women’s Media Center reveals, “In print, men wrote 62 percent of all stories in 10 of the most widely circulated newspapers. Women wrote just 37 percent.” The New York Times has the biggest gender gap out of all major newspapers, with men writing 68 percent of the articles and women only writing 32 percent.

In the 1970s, these numbers were substantially lower. After Carter was laid off from her job at the San Francisco Examiner, she searched for work in San Mateo and remembers, “I took off, got down to the [San Mateo] Times, interviewed with the managing editor there … He said, ‘Well, Bill German [editor of the San Francisco Examiner] says you know your way around the newsroom … Well, the job I am offering you is not in the newsroom. It’s in the Women’s Department.’”

At the time, female writers were confined to the “Women’s Department,” also known as the Lifestyle Department, where they wrote articles about fashion, gardening, events — and were kept out of the newsroom — the opposite of what Carter wanted.

She asked to be placed in the newsroom, where she had worked before. He simply responded: “Not a snowball’s chance in hell.”

A comment like this would dissuade many, but only increased Carter’s drive. She had worked her way up, gained the respect of her coworkers, only to have to start from the bottom again. She did, and it was her dedication to her work, along with a stroke of good luck, that changed her career forever.

On March 30, 1981, President Reagan was shot. As Carter says, “That turned out to be a terrible thing for Reagan, but a great thing for me.”

It was noon, and Carter was sitting in the empty newsroom. Everyone else was out to lunch. All of the sudden, they got news that he had been shot — there were radio reports saying he was dead, some saying he was alive, some that he was in the hospital. She was prepared and got straight to work, and by the time the afternoon paper was being passed out, she had covered one of the biggest events of that time. Her article was plastered on the front page: “Ronald Reagan: SHOT.”

Carter had worked hard, harder than many of her male coworkers, just to be seen as an equal. And her dedication and persistence had finally paid off. Had she not been working in the newsroom, and instead taking a lunch break like everybody else, she could have missed the opportunity that transformed her career. Her article proved her a valuable and strong journalist, and her manager recognized that. Says Carter, “From that point on, I laid out the paper every day.”

A few years later, in 1988, Carter became the first female managing editor of the San Mateo Times, which was a huge risk for the family-owned newspaper. “It was … a very big deal,” says Carter. “They had to decide: ‘There are no women in California, there’s only three in the whole country, should we take a chance on making a woman our top editor?’ But they did … At the time, it was truly, truly amazing.”

For Carter, being a leader was more than just a title. As a journalist, it gave her the power to give a voice to the community. “It was an opportunity to be in charge of the vision, an opportunity to share how I saw a community newspaper serving its community … how do you show leadership in a community? How do you tune into all the issues that are important to a community and serve them?”

Since her retirement from the Times, Carter has taught at colleges, mentored journalism classes and written a novel titled “From Under the Russian Snow.” Both as a woman and as a journalist, she has learned the importance of taking risks.

“Open a door. Walk through a door,” she says. “Get used to saying, ‘I think I can do that. I’ll give it a try.’” She laughs. “[But] maybe they’ll have to put up a vanity panel.”