Recently, affirmative action, specifically at Harvard, has come under fire by a new group of people: Asian-Americans. Affirmative action aims to balance the ratio of ethnicities admitted into a college, and typically benefits minorities with less access to good education. Asian-Americans, while a minority, are overall statistically more academically inclined and many achieve higher education. Thus, does not extend to them, and some Asian-Americans even believe that they are being cheated of the spots they think they deserve. According to a Princeton study published in the New York Times, an Asian-American needs to score approximately 140 points higher on the SAT than whites for admission into the same private colleges.

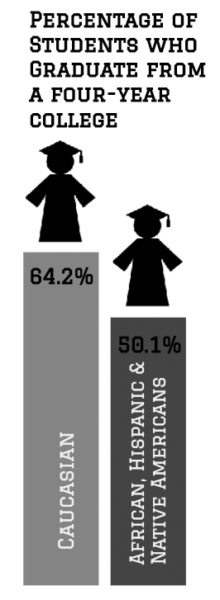

However, the “positive discrimination” in affirmative action provides invaluable support to minorities normally underrepresented in higher education. It’s more than just a policy that allows colleges to boast a diverse student population. There is a 14 percent difference in graduation rates between African-Americans and Hispanics and whites in four-year colleges, and admitting more minorities who don’t normally pursue higher education helps in bridging the achievement gap.

Furthermore, college admissions without affirmative action favor the privileged: a person with the money and time to take extra SAT lessons will likely score higher on the test. On the flipside, those who are financially challenged, dedicate their time to supporting their family, or simply did not grow up in an environment that could afford to support pursuit of higher education are then stuck with an unfair disadvantage. Many of these people belong in the minority races that are supported by affirmative action.

According to government censuses from 2007 to 2011, African-Americans have a poverty rate of 25.8 percent and Hispanics and Latinos have poverty rates of above 20 percent—approximately double that of the 11.4 percent Asian-American poverty rate. This goes to say that many of them probably do not grow up with the same luxuries of being able to get a tutor for support in a class they might be struggling in, or have time to boost their extracurricular profile around working five hours a day to support their family.

Affirmative action, coupled with extensive financial aid that most elite colleges offer, ensures that they still have a chance to pursue a path in higher education even if their academic career does not have as much to boast as some others.

Finally, “merit” includes more than numbers on a paper when it comes to college applications. A person’s merit, or their fitness in a college, is how much they can contribute to the environment in that college later on in life. This cannot be determined simply by a high score on the SAT or a research internship at Facebook that many privileged applicants can boast. Thinking that these factors entitle a student to admission to a school over anyone else is a flawed assumption.

While I do agree that for elite colleges, a certain adept for learning quickly and getting good test scores is necessary, the less than 300 point difference between the 75th percentile and 25th percentile of SAT scores is not as important as working to improve education in communities.

Affirmative action is not a policy aimed to steal spots from Asian-Americans or whites, but rather to support minorities and ensure them opportunities that they might not originally be privileged with.