Junior Lilian Shen, whose parents were born in China, feels a lot of pressure to perform well in school.

“Specifically because I’m first generation born in America,” Shen said, “my parents want me to do well in America.”

Such is the case for many Asian students. It’s no secret that Asian people are often seen as smart and hardworking, especially in comparison to other minorities. This has led some to refer to Asians as the “model minority,” pointing to the group being on average better educated and more wealthy than the overall American population.

According to a 2016 report by the United States Census Bureau, only about one in five Americans have a bachelor’s degree, but when the population sample is reduced to just Asian-Americans, that number jumps up to one in three.

Another report by the Census shows that median income for family households for Asian-Americans is $81,000, which is about $20,000 greater than the national average. However, while these statistics show that Asian-Americans are an especially prosperous group, they do not say anything about the cause.

Immigration plays a large role in Asian-American success. The selective American visa and immigration process favors literate and wealthy applicants, meaning that Asians who immigrate to the U.S. tend to be more financially and educationally successful than the average American.

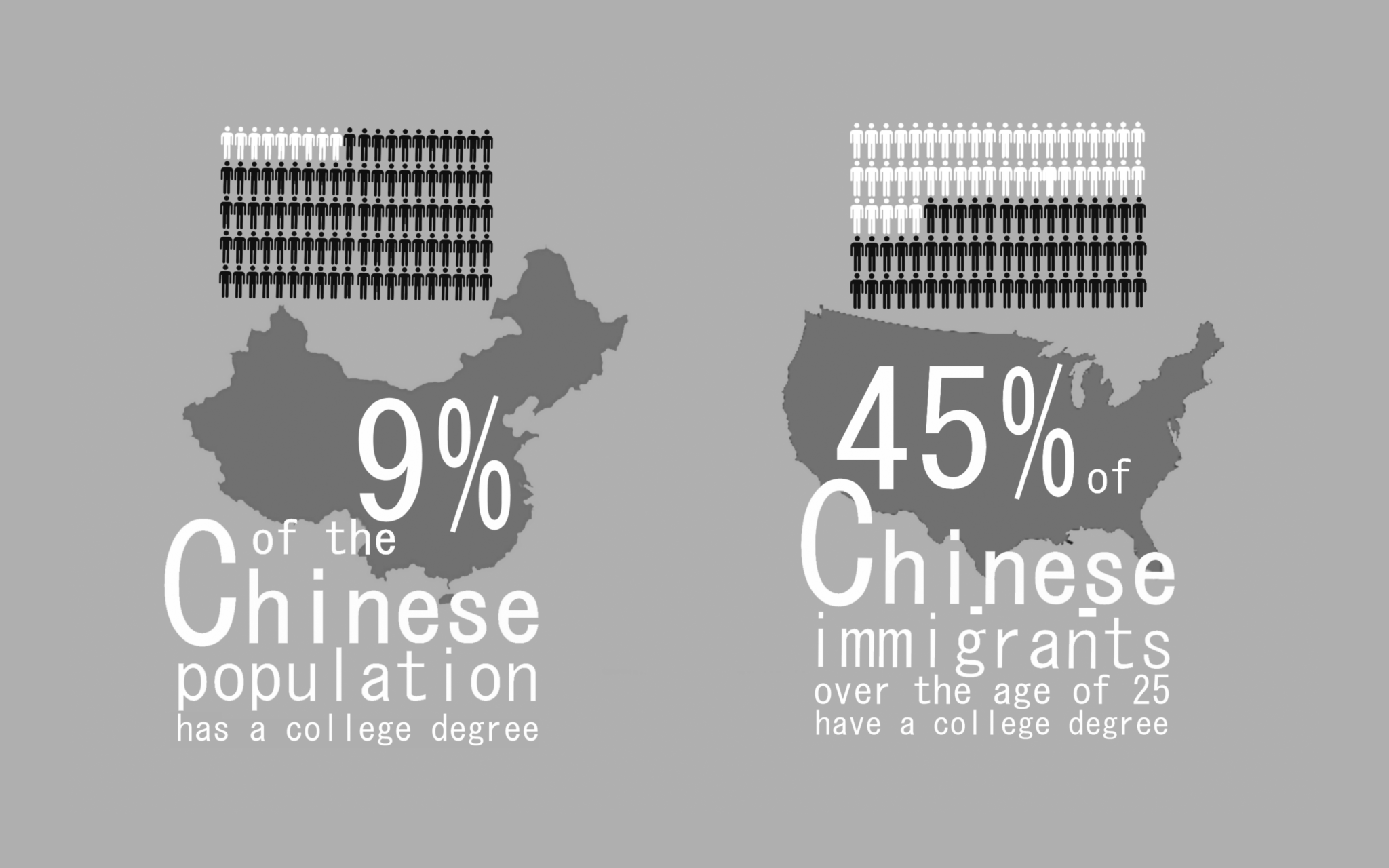

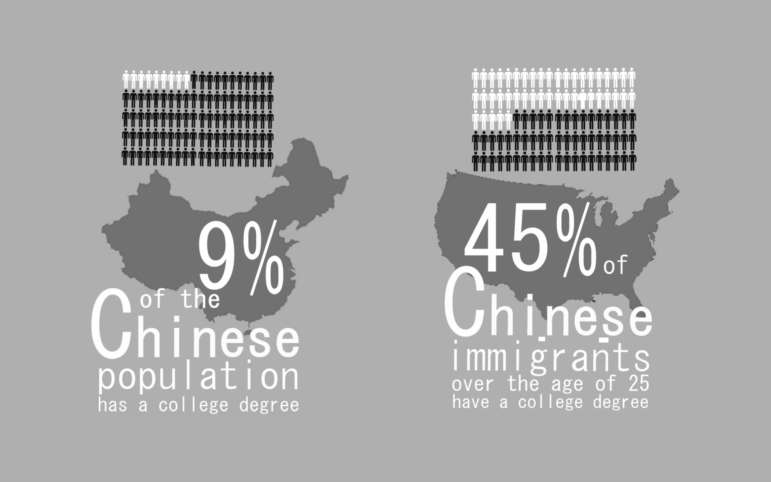

The 2010 Chinese census concluded that about 9 percent of its citizens had a college education (including junior college), yet, according to the Migration Policy Institute, 45 percent of Chinese immigrants in the U.S. over 25 years of age had a bachelor’s degree. For Mexican immigrants of the same age, however, only 6 percent had a bachelor’s degree.

Thus, it is true that Asians who live in America tend to be more successful than other minorities, but because of the sampling bias the immigration process produces, they are simply not representative of Asians as a whole.

So why does the stereotype persist? In her book, “The Color of Success,” historian Ellen Wu suggests that it is rooted in early Asian-American leaders trying to promote positive perceptions for their own race in order to gain acceptance and end discrimination. She says that during the Cold War, politicians began perpetuating these perceptions as a way to demonstrate racial equality and, thus, position itself as the flagship of democracy.

The stereotype has various effects on Asian-Americans. Shen believes Asians are frequently expected to be more successful in both academics and in other fields.

“It just applies a lot more pressure for an Asian kid to do well,” Shen said, “[because] if an Asian kid doesn’t do well, people are going to judge them for not living up to their stereotype.”

However, for freshman Simone Hsu, who is half Taiwanese, the stereotypes surrounding Asians manifest themselves slightly differently.

“I personally don’t get a lot of that bias from strangers and people who just see me,” she said. “I’m half Asian, [so] it’s not as evident.”

Despite this, Hsu still feels like there is more pressure on her to succeed than there is on her non-Asian peers.

Shen feels like some people tend to attribute her accomplishments to her race instead of her personal efforts.

“They’re like, ‘you’re smart because you’re Asian,’” Shen said, “[and] not because I study.”

On the flip side, Asians who aren’t models of academic achievement are often regarded as strange or out of the ordinary.

Shen mentioned the time she expressed frustration with a math test to another student and received the response, “Aren’t you Asian?”

However, issues with others setting expectations about one’s intellegince based on race are not exclusive to Asian-Americans.

Senior Eliana Grant, who is African-American, believes that her peers subconsciously categorize her as less competent because of her race.

“Sometimes in Biotech,” she said, “I’ll do a lab and I’ll do it really well, and I feel like [my classmates] don’t want to ask me for help because they don’t think I can do it better than them.”

Hsu believes in not conforming to others’ expectations.

“Being Asian or looking like you’re a certain type of person, people are going to have that expectation of you, and put that pressure on you,” Hsu said, “[but] you should have your own goals, you should have your own expectations of yourself, and [you should] not let other people control how you see yourself.”

Grant does not know why there is a discrepancy between perceptions of Asian-Americans and other minorities.

“There’s truth in any kind of [generalization],” she said. “It’s just exaggerated. [But] everyone’s smart in their own way, so just saying that Asian people are more smart in all aspects is totally incorrect, because not everyone’s the same; everyone is good at different things.”