THE PAST

When Irene Haas started working in the computer science industry in 1955, the world was a different place. Rosa Parks had just been arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus. Rock and roll was at its prime. And computers took up whole warehouses, requiring a massive workforce to operate each one.

In fact, at the time Haas began her job there, the computer science industry was so new that the company itself was called Computer Sciences. Haas held multiple jobs within the company.

“I started out as an administrative clerk, at the very bottom,” said Haas. “[Eventually], I was able to move up, step by step.”

After working as a clerk, she became a technical assistant, then a programmer and finally a salesperson. Interestingly, women were a minority in all of these positions—except programming. At the time, programmers translated information into “punch cards” and then fed those cards into a computer, which processed and organized the information.

“[The computer] wasn’t doing anything intelligent-wise, it was just sorting cards. But people were so amazed that a machine could do that” Haas said.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, programming was seen as “women’s work.”

Said Haas, “Women [did] menial jobs that men were incapable of doing.” Before it became a male-dominated field, these female programmers (or ‘schedulers,’ as they were called at her company) were paid little and not highly regarded. Though the programmers were predominately female, most of the supervisors at the time were men — and sexism was extremely common.

Haas recalls a time when one of her female coworkers was sexually harassed by a male coworker and stood up for herself.

“There was one woman,” she said, “[who] complained that her boss was always hanging over her … he would get close down on her.”

With the help of her fiancé, who had recently graduated from law school, the woman sued her boss. Haas believes that one of the reasons gender discrimination still exists today in the workforce is because women are shamed for standing up for themselves.

“It was such a rare thing [at the time],” Haas said, that even the women thought, ‘What is she doing? Just because [her fiancé] got his degree now they are going to sue.’”

When she moved up to male-dominated positions, sexism was a daily obstacle. While working in technological support, she was one of three women compared to 40 men. She was sexually harassed constantly.

“When we would have these [board] meetings, there was this one guy I used to have to be careful not to sit next to … because we were at a table, and he would put his hand on my thigh.” Haas said.

She did not report it.

“If that happened to me 50 years ago, and it’s still going on,” said Haas, “maybe [it is because sexual harassment] is not being addressed.”

THE PRESENT

Sexual harassment and sexism are still extremely prevalent in the technological field. A 2016 study focusing on women who worked for tech companies in Silicon Valley found that 60 percent of women had, at one point, been sexually harassed, and only about half of these women reported it. Additionally, 90 percent of women have received sexist or demeaning comments from their male coworkers.

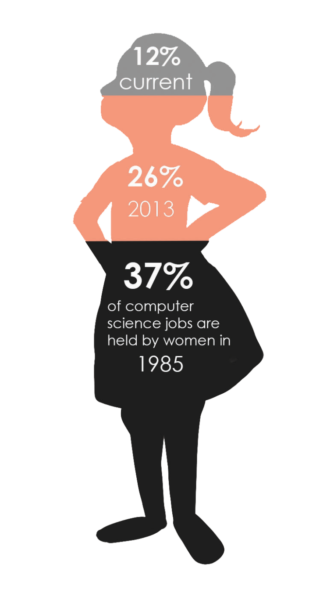

Most people would expect the number of women in the tech industry to have increased in the past few decades. However, that is not the case. According to the American Association of University Women, the percentage of women in computer and mathematical occupations has continued to decline since the 1990s—in 2013, a mere 26 percent of positions in the field were held by women.

Conversely, young girls show a high interest in STEM fields. A study conducted by Microsoft found that, around age 11, there is a high percentage of girls interested in the STEM field—but at age 15, there is a massive decline.

Why do girls lose interest in the math and sciences in high school?

“Conformity to social expectations, gender stereotypes, gender roles and lack of role models continue to channel girls’ career choices away from STEM fields.” Explained Martin Bauer, a psychology professor that contributed to the study.

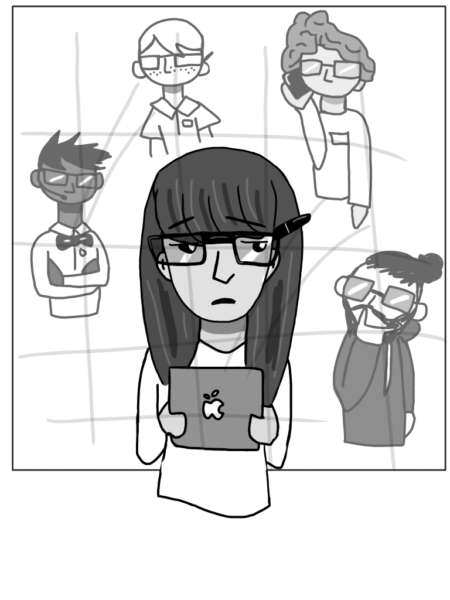

Emily Schienvar, a spokeswoman for Girls Who Code—an organization dedicated to closing the gender gap in programming—says that gender stereotypes and the way computer programmers are portrayed impacts the amount of women in the field.

“The image of a programmer is of a boy in a hoodie in a basement alone,” said Schienvar, “girls look at that and say ‘No, thanks.’”

She attributes the rise of women in medicine and law to the changing images we see in popular culture.

“In the 1970s, less than 10 percent of women were lawyers and doctors. Now that number is 40 percent … The impact of television shows like ER, Grey’s Anatomy, LA Law cannot be overstated.” Schienvar continued, “We need to change pop culture and the image of what a programmer looks like and does.”

Haas agrees that a lack of exposure and role models result in less women being interested in the STEM field, specifically computer programming.

“Experience and being introduced to it—that’s a big one,” said Haas. “My daughters [and my grandaughter] are in the computer industry … it’s a matter of introduction.”

Non-profits, such as Girls Who Code, are dedicated to closing the gender gap, and have already succeeded in igniting an interest in computer programming among girls. By the end of the year, the program will have reached over 50,000 girls through free, after-school clubs all over the country.

“According to surveys after our programs,” Schienvar explained, “many girls state that they are more interested in computer science or going to major in computer science.”

Schienvar mentioned that as the company was founded in 2012, and their first class of girls will be graduating college in the next few years.

“We’re excited to see the incredible things they’ll accomplish.” she said.

As they enter the workforce, female computer programmers face a whole new set of challenges. A statistic by Glassdoor, a career review site, states that in Silicon Valley, female computer programmers have the highest pay gap out of dozens of other tech jobs, such as engineers and analysts — making nearly 30 percent less than their male coworkers.

The gap is worse for women of color, and may be part of the reason these women pursue different careers. A study conducted by the Kapor Center for Social Impact examined the reason why so many women were leaving their jobs at tech companies. The study focused on the discrimination against latino, black and LGBTQ women. It found that a third of underrepresented women of color were ignored for promotions.

THE FUTURE

Haas smiles at the fascination people used to have with computers. She remembers them staring wide-eyed at the massive, mysterious machine and struggling to comprehend its magnitude.

“The front of our building was all glass, so people could look in and see the tapes spinning and these things sorting,” she recalled.

People stood outside the window and watched the key-punch operators work.

“They decided it wasn’t safe. They sealed it all up.”

Even with glass walls, the discrimination and sexism that goes on inside the tech industry is hidden. The only way to expose the injustices women face is by turning the glass on its side and breaking through.