After teachers pass back the results of tests or projects, classrooms are often filled with the sounds of students discussing their grades. Students compare the scores they received with a sense of eagerness or, sometimes, disappointment at not getting the grade they had hoped to get.

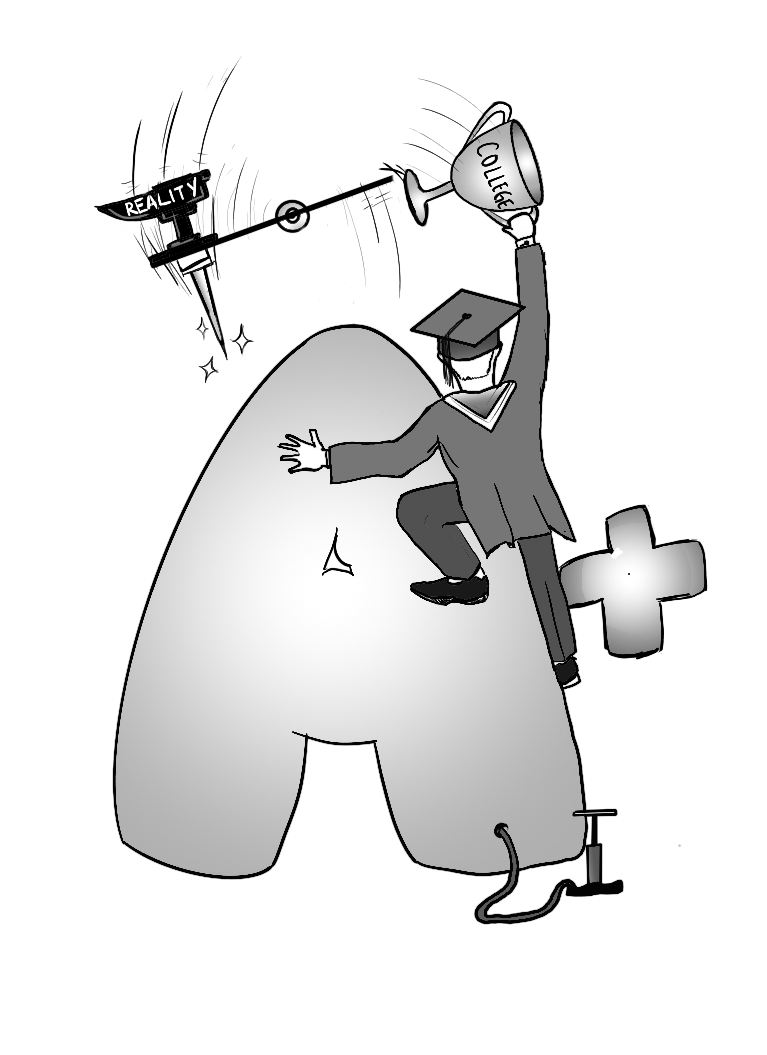

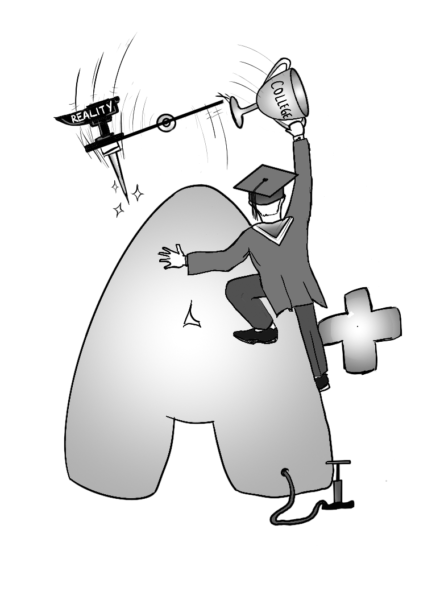

It’s no secret that Aragon is a school community made up of many driven individuals. Nowadays, however, it has become a question of whether most students are driven by grades or by the learning experience. Because Aragon is often perceived as a school known for its academic rigor, we have fostered an environment in which some view an “A”as expected instead of exemplary.

Grade inflation, which is when students are given higher grades than they may actually deserve for the effort they put in, helps perpetuate our common notion that anything less than perfect is seen as “below average.” Though some people hold this view, it is important to remember that this is not the reality.

In other educational systems abroad, a C is seen as the acceptable average, according to senior Julia Cot, who attended school in France. In comparison to those systems, she and senior Adrian Braanemark, who moved to the United States from Sweden, feel it is easier to get an A here.

While grade inflation can sometimes give students the extra time to understand the material and can even help alleviate stress by making a higher grade the incentive, it can also cause a shift in the way we perceive academic success, by making learning closely tied to getting a particular letter grade.

It can also become a problem when a large percentage of students have an A that they may not have earned because they have “learned and mastered” the content with confidence. Moreover, when a majority of the students have similar GPA, college admissions officers are more inclined to put greater emphasis on standardized test scores, which many students are against.

Though we may feel that grade inflation is beneficial to our GPAs and chances at admission to top universities, in some ways, it is harmful to the way we approach school and the learning process.

Through grade inflation, both teachers and students dilute what it means to receive an A when “high grades” become the academic standard. Senior Maitlyn Lang, who moved to San Mateo from New Jersey at the beginning of junior year, finds that an A held more value at her previous school than at Aragon.

In comparison to other high school students throughout the United States, it is possible that we have forgotten what each letter grade is supposed to represent. Rather than making it about getting into college or simply getting the work done, getting an A should mean that the student’s work is exemplary or that they have mastered the content for the unit.

Although some people may not be comfortable with getting what they would consider “bad grades,” our experiences at school should always be about how much we have learned instead of what grades we’ll be sending off to colleges when the time comes.

Rather than having separately weighted categories for quizzes, tests or homework, for example, students at Aragon would benefit more from a system that assesses us on how much we have mastered the content from a particular unit.

Instead of feeling like we need to work hard to raise our test category, we would be able to focus our time and energy on making sure we have learned the material under a system that more closely evaluates content mastery.

While we understand that teachers often just want the best for us, we need to reevaluate the way we view academic success. We may be getting the grades that we want, but we must also ask ourselves if we are learning the material to the best of our ability.

A drastic change in mindset is, of course, difficult to adopt. While there is no true harm in wanting to work hard and get good grades, we need to reevaluate the true value of an A and remember that grades are meant to be earned.

At the end of the day, our understanding of the topics we learn at school should be the most valuable part of the learning experience. Though we may be satisfied with how our report cards look in the short term, grade inflation has negative long-term implications to the way we approach the learning process.