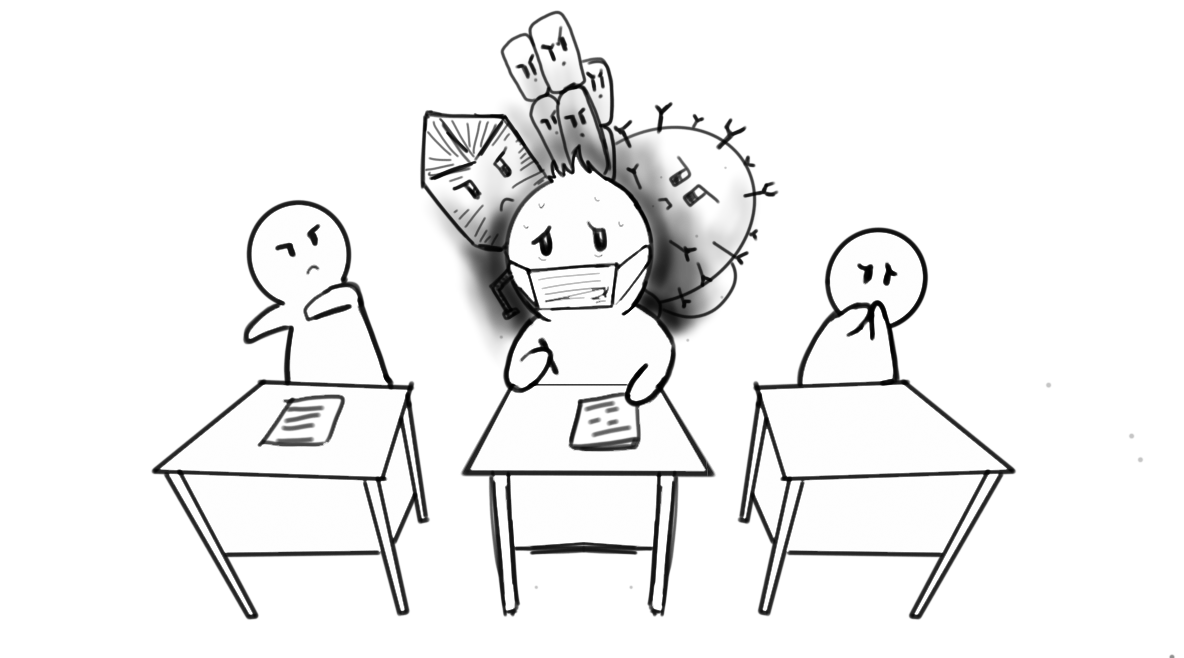

Look around a class, especially during winter, and one can often find the telltale signs of sickness: red nose, baggy eyes, a Thermos of tea, a personal tissue box or, even worse, constant sniffing. Despite possible encouragement by the school or parents to do otherwise, it is the norm for many to attend school even while sick.

“I think the fear of missing out on classwork or an activity motivates people to go to school when they’re sick,” said sophomore Rika Yang, “and it’s the same for me.”

Back in elementary school, sick days were spent watching cartoons or playing, but as students grow older, more is expected of them, and the pressures to power through sickness grow.

“In college they don’t really care, you just don’t do your work,” said alumna Nicole Chang. “You just get a zero on the assignment. So, in the long run, it’s mostly on you.”

Even once one enters the workforce, there is still little relief from the pressures. According to a study by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, only seven states and Washington D.C. have state enacted sick leave policies. Fifty-eight percent of full-time employers and 25 percent of part-time employers offer paid sick leave. But for most, the bar for staying home sick is high.

“Having a fever would be a big thing,” said Chang. “If I had the actual flu virus, I probably wouldn’t go to school as well.”

She recalled a time when she went to school sick.

“I drove myself to school, and I started to feel dizzy. I wasn’t able to focus at all,” Chang said. ‘That was one time I probably shouldn’t have gone to school … I couldn’t focus the whole day and I ended up just going home.”

Other students’ experiences going to school sick have ended similarly.

“I went to school just for my first period class to take really important notes for an assessment on the unit,” said junior Nathan Villafria. “I had migraines and headaches, and it was something I considered to be quite bad, so I did go home afterwards and just hopped back into bed.”

AP Biology teacher Katherine Ward finds that, although students may initially be strong-headed, it doesn’t take much to change their minds.

“A lot of times, if they are truly sick, all it takes is someone to say, ‘You know what, you don’t look so good, you should go home,’ and that sort of gives them permission,” said Ward. “They were sort of denying, ‘No, that’s not what this is,’ but when someone else notices, they’re like, ‘Maybe this really is the case.’”

The need for teachers to encourage students to go home illustrates that parents oftentimes fail to prevent their sick student from attending school. According to a survey by the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, 42 percent of parents would send their children to school after vomiting, and half would not be deterred by a fever.

People also tend to only worry about the schoolwork they may miss or have to make up, disregarding their risk of infecting others.

“It’s your own selfish motive,” said Villafria. “Because people think, ‘Oh, I’m sick, I’ll be fine. ’”

But viruses and bacteria have evolved to spread. They make people miserable, but not enough to constrain them to bed. Microbes which infect people, like the common cold virus, have evolved to rely on humans for transportation to other humans. Thus, it must leave the human well enough to move around, but it must also keep the body coughing, hacking and sneezing so the virus can spread.

But going to school sick can have greater consequences than simply infecting another person. To some people, catching a cold could be far more serious than a few days’ worth of coughs and sneezes. “You don’t know where there’s a kid in here who is immune-compromised because they’re battling cancer, or … have a blood disorder,” said Ward. “And so we bear some responsibility for making sure that everyone else stays well, not just that we stay well.”