Written by: Kimberly Woo and Emily Xu

With origins dating back to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, affirmative action, as defined by the West Encyclopedia of American Law, currently “refers to both mandatory and voluntary programs intended to affirm the civil rights of designated classes of individuals by taking positive action to protect them [from discrimination].” Such laws and programs, usually instituted in higher education and the American workplace, generally have goals of promoting diversity and making up for past cases of discrimination. This, however, was not always the case.

Coined in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy’s Executive Order 10925, affirmative action initially referred to a policy of anti-discrimination in employment for all contractors that did business with the federal government. At this point, racial minorities and women were not given any preference. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 took a similar interpretation of affirmative action when it prohibited discrimination in employment for all firms that had more than 15 employees. Again, there was no racial quota requirement enforced.

However, in 1968, the Office of Federal Contract Compliance required employers to meet certain racial quotas to evaluate the effectiveness of affirmative action. A few years later, some colleges and universities also began to adopt this version of affirmative action in their admissions process.

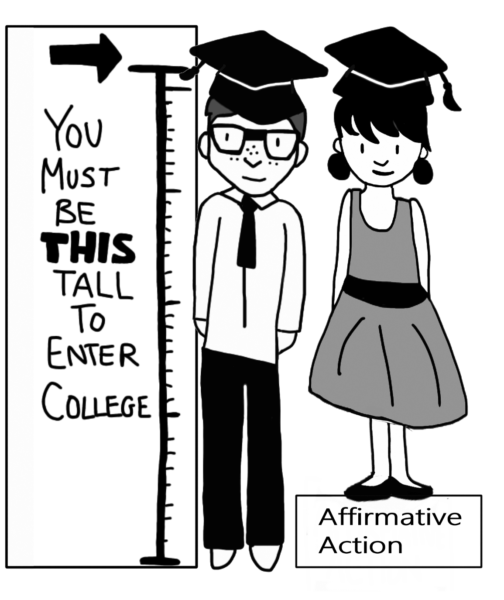

Then, in 1996, California passed Proposition 209, which effectively eliminated affirmative action by deeming racial quotas illegal in both education and employment within the state of California. Outside of California, however, schools may still use race as an admissions factor because of a Supreme Court ruling in 2003. The court ruled in Grutter v. Bollinger that, although affirmative action’s initial purpose of redressing past civil oppression is no longer justified, the promotion of diversity within school campus is a valid reason to keep race as an admissions factor.

At Aragon, students have varying opinions on affirmative action.

“Let’s say life is a race and one type of person gets a 50-yard head start and everybody else doesn’t,” said senior Eliana Grant. “You got to make the playing field even.”

“I support all kinds of affirmative action,” said alumna Emily Shen. “Gender-based affirmative action is important when it comes to college admissions at predominately-male schools … or the tech sector where a lot of people are predominantly male … [For] college admissions, we should move more toward class-based affirmative action in the sense that there are very poor white people versus very wealthy black people … But I’m also a supporter of race-based affirmative action … because even if someone is a wealthy black person or a wealthy Latino, sometimes they still face barriers at their school or in everyday life that can still interfere with how they do things or the opportunities they live in.”

Conversely, others have disliked the idea behind affirmative action because it creates division between races.

“[Affirmative action] divides [races] even more than it needs to,” said sophomore Taylor Jackson. “We’re trying to come together, but that doesn’t help if you’re going to separate us … I feel like they make minorities a charity case. They’re like, ‘Oh, it’s OK if you have OK grades. You can go into this college.’ I want to work hard enough to earn to be accepted. It makes me feel like a charity case.”

Others say that affirmative action takes away job positions from more qualified individuals.

“I see [affirmative action a little] as a negative,” said junior Adam Bever, “because it’s like someone could lose a job because they’re not a certain race even though they’re more qualified for the job.”

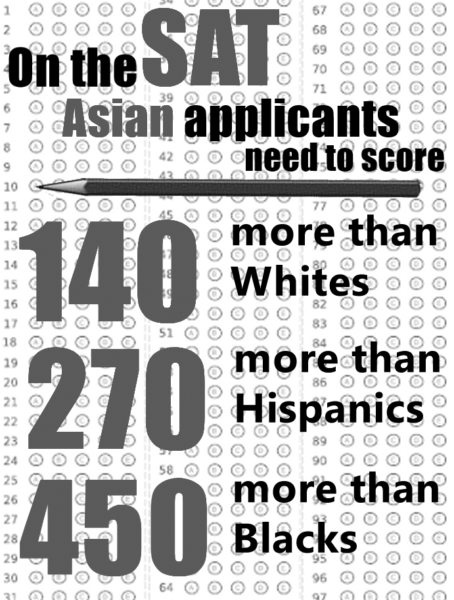

Some elite public and private colleges have factored race into their admission process. In fact, a 2009 Princeton study shows that colleges have raised standards for how students are admitted: “Asian-American applicants had to score 140 points higher on the SATs than white applicants, 270 points higher than Hispanic applicants, and 450 points higher than black applicants in order to have the same chance of admission at top universities.”

Shen provides insight into a common Chinese-American mindset.

“There’s this test at the end of your senior year [in China],” she said. “With the test, you can only take it once … Their college admissions have nothing to do with the holistic process that we have here for private colleges. You do well on this test, and according to your score range, you get into college. In general, Chinese-Americans [might] believe that because that’s how it was back then or is back there, you’d think that everything is very predictable.”

However, Shen said she is not against affirmative action.

“To me, though, I don’t think that [holding Asian-Americans to a higher standard] is unfair because I have more resources than most people,” she said. “I have parents that will pay for SAT prep classes, I have parents who will [say,] ‘Oh, you don’t have to worry about us paying the bills. You don’t have to work a job and then you can study on SATs instead or focus on school.’ Because of my background, I think it seems perfectly fair that, because I come from a more privileged background, there will be higher expectations.”

But students like Bever believe that those who get a job or a spot in college based on affirmative action should still be qualified.

“If someone who’s qualified and got the job and a little affirmative action played a part, I wouldn’t have a problem with it,” Bever said. “But if it’s someone who’s not a good person… [or] who got a spot because of affirmative action [and] isn’t quite as qualified for the spot they’re given, then … I just wouldn’t be happy that this person got the job or a spot in a college over someone who’s more qualified just because they’re a different race or a woman.”

Other students, like junior Laurel Bolts, support affirmative action, and said that it gives opportunities to those who deserve them.

“Of course, there [are] people who are going to say, ‘Oh, they shouldn’t [be accepted] because of [affirmative action],’” she said. “You should see that that person pushed themselves to get there because of who they are and their race. You judge because they took from your own, but they took it because they deserved it, not because they shouldn’t have it just because of their skin.”

Other students agree that race should be taken into account in college admissions, but that they should be considered along with other factors like extracurriculars and academic records.

“I think [colleges] should [take into account race] because it would add more diversity,” said junior Emily Gavidia. “Stepping foot on a campus, you want to be able to see your group and feel welcomed. If you don’t see yourself represented in that community, you’ll feel more [excluded] and it’s just better to have that diversity.”

“I think that they should accept the person that has better grades but also take into account like them as people and take in their situation more so because just based on race, you can’t be told a lot,” Gavidia said. “You want to see how this person grew up, the kind of opportunities that they had as a person, not just like how they were raised up just by their race as well … their social status, how much money they had, what classes they took, what extracurriculars they took … and see which one had better had better opportunities.”

Despite having over 50 years of history, affirmative action policies remain heavily debated, and as the minorities will soon become the majority, more questions will arise over its implementation.

Additional reporting by Caroline Huang