There is also an obstacle that no amount of government policy will be able to solve: stigma. Addiction is accompanied by a whole host of presumptions and stereotypes. One stereotype is that people who are addicted chose to go that route, and thus must suffer the consequences. The other, equally debilitating and prevalent, is the “not me” presumption.

The poison of stigma is that it obscures the issue, creating a negative stereotype and simplifying a deeply complex problem, which all contribute to a psychological barrier that impedes progress.

We always assume that something like addiction won’t happen to us or to our family. This thinking provides the fuel for the stereotypes that accompany addiction, as it draws a line between “us” and “them,” assuming that “we” will never fall victim to such poor decision-making, and only the proverbial “they” will.

As an idea, have you ever gone on a walk to fight addiction? Have you seen or heard about major fund raising efforts to deal with the opioid epidemic? Society has wide funding for cancer, social media efforts for ALS and big fund drives for infectious diseases, but addiction is pushed to the periphery. Initiatives to fight things like opioid dependency are obscure and poorly advertised as compared to cancer or AIDS. The obvious reason for this, of course, is simple. If addiction is a “them” problem, why should “we” worry about it?

Cancer, Acute Myeloid Leukemia, infectious diseases — these are all things that can affect any one of us, and we know it, and that’s why we fight it. In addition to that, people rarely get blamed for getting cancer — smoking aside — or really most any disease. Addiction, on the other hand, is something seen as a choice, giving further reason for the public to push it aside.

This thinking is logically flawed on two levels. The first is that addiction isn’t a choice, but rather a chronic mental disease. The second is that addiction affects people from all backgrounds, illustrating there is no unitary cause and that each person’s situation is unique.

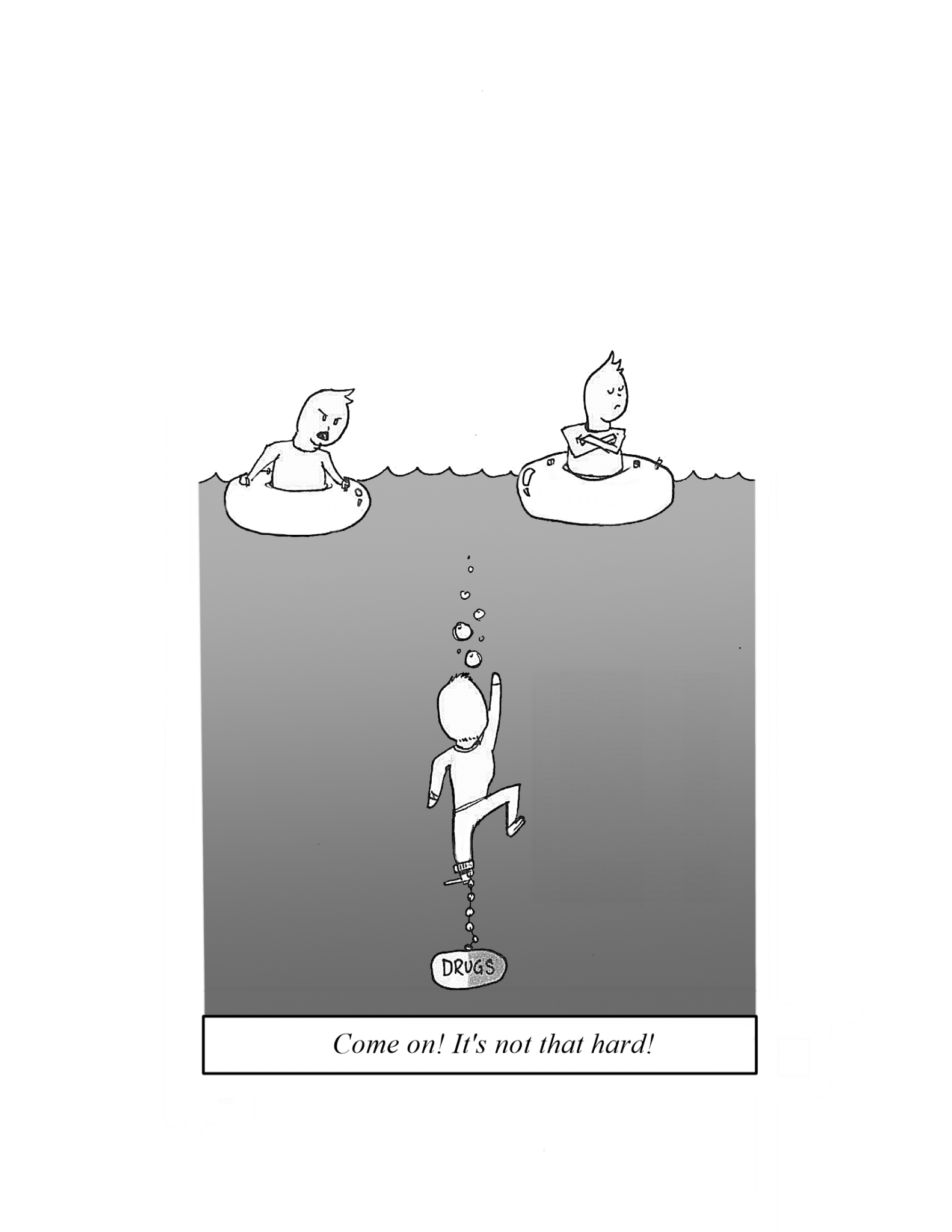

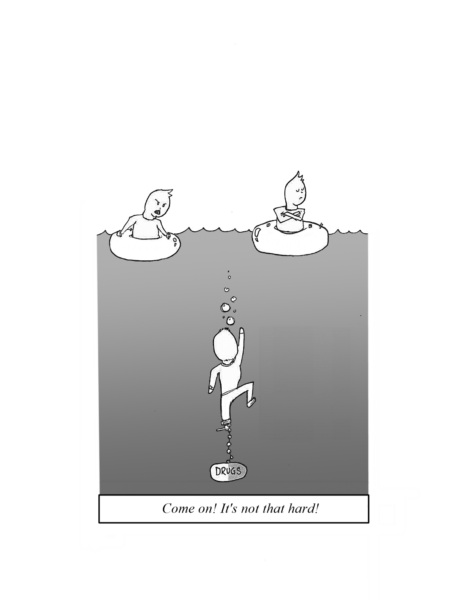

While there is a series of decisions that lead to addiction, once it takes hold of the brain, the person is at the mercy of the drug, and it stops being a choice. Society often points toward this series of decisions as simply poor decision-making deserving of the negative stigma. But, given that each person’s situation is unique, the assumption that addicts are always fully responsible for their addiction and thus must suffer the consequences is simply incorrect.

I have only had a glimpse into the minds of students who have dealt with or deal with addiction, and I have only an intermediate understanding of the science and health care behind the problem. But from what I know, one thing has become blatantly clear: the stigma around drug addiction, especially the one that it is a “choice,” is illogical and arrogant.

It didn’t take me long to realize that if I was in one of those situations, there is no guarantee I would have taken a different route. A whole host of issues — some I have personally experienced in lesser degrees or have seen in loved ones in varying degrees — can cause or foster addiction.

In essence, nobody, including myself, has the right to judge those who suffer from addiction. The whole stereotype around the issue comes from willful ignorance and the faulty belief that “we” will always be smarter and make the right decision.

People have enough trouble trying to figure themselves out, so why is it okay to think we have everyone else figured out and can judge and categorize them?

The answer is we don’t, and once we get that little sliver of awareness, we are on the path toward accepting addiction for what it is: not a choice, but a chronic illness that needs to be treated instead of ostracized or held in contempt.

It is time to stop thinking we are in any place to judge those who are addicted, and time to start figuring out ways to find them help and provide them with the support they need, before this epidemic breaks the “us/them” barrier, and affects you.