Written by Michael Herrera and Ashley Tsang

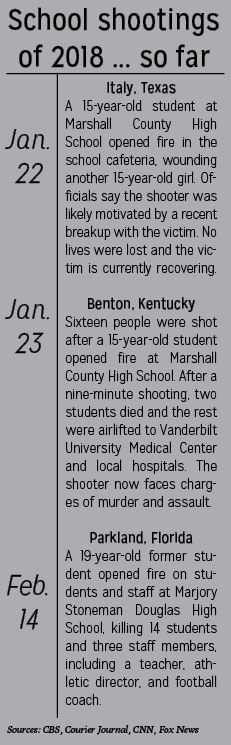

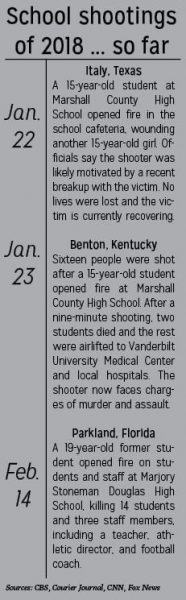

The Feb. 14 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida has made school safety a topic of national discussion.

Though the U.S. lacks a federal law requiring all states and schools to have a comprehensive safety plan, California is one of 33 states that requires every school or school district in the state to include one. For all schools in San Mateo County, “The Big Five” is the comprehensive plan that describes five standardized actions that all students, staff and faculty should take depending on the emergency event.

The Big Five was the result of the San Mateo County’s Coalition for Safe Schools and Communities, a collaborative effort between county schools, law enforcement and emergency services that was founded as a reaction to the 2013 mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut.

“[The Big Five is] run by the entire county and what’s nice about that is that all the schools follow the same procedures, the police, the fire department, so if somebody says one of the names of one of these procedures, all people involved in emergencies know and understand what’s going on.”

The Big Five describes the following procedures: “shelter in place” to protect against environmental threats, “drop, cover and hold on” for earthquakes, “secure campus” in the event of a potential threat of danger on campus, “lockdown/barricade” for an immediate threat of danger and “evacuation” if off-campus conditions are safer than on-campus conditions.

“[The Big Five is] run by the entire county,” said Assistant Principal Lisa Warnke, “and what’s nice about that is that all the schools follow the same procedures, the police, the fire department, so if somebody says one of the names of one of these procedures, all people involved in emergencies know and understand what’s going on.”

Teachers are expected to know The Big Five in order to take proper action depending on the emergency, but the majority of students at Aragon are unaware of the standardized procedure. In a survey of 199 students, the Outlook found that only 7 percent know what The Big Five is.

However, while many students may not know The Big Five by name, they understand its central principles of, dependent on the emergency, sheltering, locking down or evacuating.

Staff are generally confident in their ability to respond to emergencies, but a significant percentage hold reservations. An Outlook survey of staff asked “How confident are you in your ability to respond to an emergency at school?” and 56 percent are confident or very confident, but 24 percent are not confident and 2 percent are not confident at all.

Emergency drills implemented throughout the year are designed to practice The Big Five procedures.

“Sometimes we have drills and sometimes we have things that come up on campus,” Warnke said. “It’s usually about once a month, but sometimes it’s just that we end up — like [the Feb. 27 fire incident] — evacuating.”

The number and types of drills are coordinated by the schools, and the San Mateo Police Department is involved during practice.

“On our campus, we have school resource officers that are dedicated to students and staff there,” said SMPD Sgt. Amanda Von Glahn. “With that, there’s drills done in cooperation with our school resource officers and school staff to practice whether it be one of the protocol guidelines which is lockdown, secure campus, evacuation, whatever it may be that might dictate that emergency.”

Though Aragon implements emergency drills during the year, many do not believe that there is enough routine practice. According to the survey, more students think Aragon should have more emergency drills (49 percent) than think it has enough (43 percent.) Staff feel even more strongly, with 64 percent saying that the school should have more drills.

Besides the number of drills practiced, how seriously students, teachers and faculty take them is another factor in the efficacy of preparation.

“[Drills are] just kind of habitual … It just doesn’t have much value when they do it,” said senior Keertana Namuduri. “It’s just kind of like, ‘This is something we have [to] do, so we’re just going to do it.’”

Many students are ambivalent about emergency drills, with 42 percent saying they take them “neither unserious nor serious.” At the same time, 34 percent take drills seriously or very seriously.

However, staff take drills far more seriously, with 58 percent saying they take drills seriously, and 20 percent saying they take drills very seriously.

Photography teacher Brooke Nelson explains the thorough emergency drills and training procedures practiced at her previous school.

“The Hayward police department spoke to all staff and faculty at Moreau providing safety information and instruction for a possible shooter on campus,” Nelson said. “Then, in the classroom setting, the school performed numerous drills for different scenarios that students and teachers could find themselves in for an active shooter on campus … I remember hiding in a storage closet with a group of my students for five minutes and we had to remain quiet as a mouse so no one would find us. These scenario drills helped me feel more prepared and established some plans in place if a shooter situation presented itself.”

In the event of an active shooter on campus, according to The Big Five, lockdown and barricade would be the immediate response, but depending on individual circumstances, evacuation from school grounds may be more appropriate.

“I think that is what makes our community safer — it’s that we care about each other and that we make sure that if something doesn’t seem quite right, you guys talk to adults about it. And that makes it a safe place to be.”

“There’s a fight, flight or hide terminology that’s being used … It kind of goes back to being observant, being aware of your surroundings,” Von Glahn said. “In the event of the threat and if a student feels that it’s not affecting their area and they can get away, then get away. It’s a quick evaluation of what’s unfolding that person, that student, that staff member would have to make at that point.”

Student confidence in staff preparedness for emergencies is lukewarm. In the Outlook survey, 37 percent say they are confident that “Aragon staff are prepared for emergencies, including active shooters,” but 38 percent said they are neither unconfident nor confident.

Lack of majority confidence was evident in mixed staff responses to the fire alarm on Feb. 27 which was later confirmed as accidental. While most teachers evacuated, some decided to remain in the classroom.

“The prior week we had a shutdown, a lockdown drill, the day there was a threat, and we were told to, if there was a fire drill, to stay in our room until there was an announcement,” said math teacher Adam Jacobs.

Jacobs was referring to the decision by the administration to lock all classroom doors and secure the campus in response to a non-credible threat made against Aragon on Feb. 26, six days after the attack in Parkland.

“Then the next week there was an actual fire alarm,” he said, “and so I was just following the same protocol as we had just discussed the week before … It seemed to be that [all of my students were] sort of with me in terms of following what had happened before, and especially given what happened in Florida … it was a little too close to that and too close to our threat before, but now it seems to be very clear. There’s school protocol, but in an emergency situation, the teacher has to make a judgement call.”

Clarification of proper response to fire alarms was made in the all-staff meeting on March 1. Unless instructed over the P.A. system to remain in classrooms, all are to evacuate school buildings as normal.

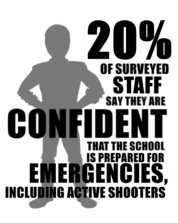

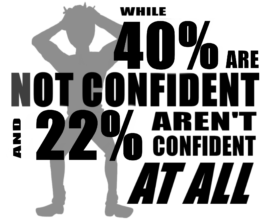

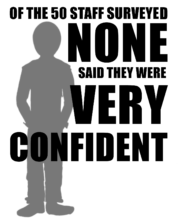

However, despite their new training, staff confidence in school preparation is low. In response to “Do you believe that school is prepared for emergencies, including active shooters?” a majority of staff expressed a lack of confidence: 40 percent are not confident and 22 percent are not confident at all. Only 20 percent said they are confident while none said they were very confident.

The survey began collecting responses five days after the all-staff meeting.

Von Glahn explains how students and families can better prepare for emergencies.

“What I would ask our students and staff to know inside and out is our Big Five protocol, for when they do hear a specific term specific to The Big Five, they know it and they do it on top of using their instincts,” she said. “I would say [for parents to] sign up for Nixle [an alerting system by the police department], it keeps you in the loop with what’s going on … and communicate with their kids and make sure they’re having dialogue about in the event of a threat what would you do, and kind of pick their minds about making sure they know to be observant and aware of their surroundings.”

Not only is communication between parents and children important, but it is also necessary among community members and the school to ensure a safe environment on campus.

“I think we have a wonderful community here at Aragon, and when there was a stressful situation last Tuesday [Feb. 20, when the non-credible threat was made against the school], many students and staff came and reported concerns, and we talked with every person that there was a concern regarding and made sure to investigate all those things and not in a way that students were in trouble,” Warnke said. “And I think that is what makes our community safer — it’s that we care about each other and that we make sure that if something doesn’t seem quite right, you guys talk to adults about it. And that makes it a safe place to be.”

Additional reporting by Ray Chang, Zack Cherkas, Caroline Huang, Eric Shen and Justin Yang with survey data collected by the editorial team. Infographics by Ray Chang.

The student survey had 200 respondents, the staff survey had 50 respondents. All poll results can be found at tiny.cc/outlooksafetysurvey