Written by Rosella Graham and Alyce Thornhill

This past year, not only have movies featuring historically marginalized groups been wildly successful in the box office, but they have also been a hit at award shows. The 2018 Oscars set multiple new milestones for inclusivity: Jordan Peele became the first African-American man to win Best Original Screenplay, and Chile’s “A Fantastic Woman,” directed by Sebastián Lelio, became the first film with a transgender woman as its lead to win an Oscar.

While it may seem that the disparities in racial representation in film have begun to close, the data suggest that there is still a ways to go.

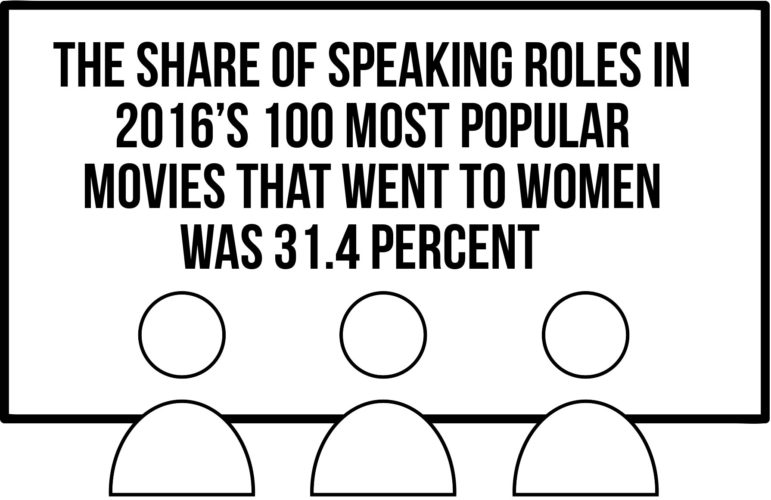

A 2017 study from University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism examined 900 of the most popular films from 2007 to 2016, and investigated characters for diversity in regards to gender, race, sexuality and disability.

The study found that representation has stayed the same for the past 10 years, and the number of directors from minority groups has actually decreased.

Regarding Native American characters, representation in prominent films is virtually non-existent — out of the 100 films of 2016, none featured any Native characters.

Native American activist and artist Calina Lawrence believes that the recent push for diversity signals hope for all marginalized people, especially Native Americans, who have been left out of Hollywood for decades.

“I think that black and brown solidarity will break barriers in the film industry because all of our non-eurocentric cultures incorporate storytelling,” Lawrence said. “It’s inevitable that we control our own narratives now that we have modern tools to utilize.”

An inability to control one’s own narrative leads to inaccurate storytelling.

“Native people in particular are almost always portrayed in a historical context in mainstream entertainment,” Lawrence said, “and it perpetuates the idea that we are a thing of the past rather than the present.”

Lawrence dislikes that the Disney movie “Pocahontas” reinforces the incorrect belief that all Native American tribes are the same.

“Not all Native nations resemble the Sioux teachings — tipis, buckskin, plains scenery,” said Lawrence, who is part of the Suquamish Tribe of the Pacific Northwest. “This leaves out hundreds of cultures based in crucially different landscapes of the country.”

But the problem reaches beyond just “Pocahontas.” Lawrence said, “Almost all old western-shows [and] movies portray Native characters (typically white actors in red-face) as either savage and threatening, noble savior, and or magical spiritual creatures rather than human beings.”

On the other side of the spectrum of accurate representation stands Pixar’s Coco. Spanish teacher Ana Maria Ramos appreciate’s it’s use of cultural items relevant to her Mexican heritage.

“‘El mandil’ in Mexico is not just the apron,” Ramos said, “it takes you to the history and the indigenous people and represents Mexican culture and family.”

Ramos also appreciated that “Coco” was not only a tribute to Mexican culture, but it also alluded to many of the struggles that Mexican immigrants and Mexican-Americans face today.

“When [the grandfather] was trying to come to the other side he wasn’t allowed because his picture was not on the offering, I told my mom that [I thought] it represented crossing the border and the picture was his identification and documentation and visa,” Ramos said. “I can see … the struggle so many immigrants go through each day when coming to this country.”

Similarly, the movie “Black Panther,” illustrates the struggles African-Americans face today.

“They talked about what it is [like] to be African-American in Oakland,” said senior Marlena McVey, “and that whole … fight that we are still going through now to get the equal rights that we all deserve.”

For junior Laurel Bolts’ family, “Black Panther” renewed a sense of pride in their heritage.

“My sister is really getting into her African roots,” Bolts said. “She’s trying to grow out her natural hair. … She wanted to be proud as her African self.”

McVey appreciated the character development and prevalence of African-American actors in “Black Panther.”

“Normally, African-American characters are the secondary characters,” McVey said. “A lot of times, they are the character you’re supposed to laugh at, and not so much the person that you’re watching grow and progress into a better version of themselves.”

Bolts believes that T’Challa is a strong role model for young black boys, as “he leads.”

Similarly, the main female characters, Nakia and Okoye, are strong role models that Bolts believes young black girls need.

“Finally, young African-American girls will have another Halloween costume besides Princess Tiana,” Bolts said.

Even with the push for inclusion and diversity, many minority groups are still left out. Lawrence, who attended the 2018 Golden Globes with actress and activist Shailene Woodley, became particularly aware of this disparity.

“It was exciting and disappointing at the same time,” Lawrence said. “But bringing media attention to the fact that the majority of women nominees were European-American just shows that there are not enough roles created for Native women.”

Lawrence believes the continued mistreatment of Native groups can make better representation an uphill battle.

“We know that Native women have been dehumanized in many ways at the hands of Hollywood,” Lawrence said. “When we do [make it to Hollywood] we’re still usually fighting for justice and dignity rather than enjoying that ideology of success.”

Lawrence attended the Golden Globes because of her involvement with the “Time’s Up” movement. Though she felt included and empowered by the other women who were part of the movement, she quickly noticed the diversity issue within the “Time’s Up” movement as well.

“If Shailene and I had not been friends for years before this event, then I don’t know if any Native women would have been invited,” Lawrence said. “This goes to show that inclusivity has to reach the most vulnerable. We from marginalized [and] oppressed communities have to be thought about from the beginning stages of planning as opposed to being the afterthought.”

For decades, film and media have shaped the way that many minorities view themselves and the way they are viewed by society.

Lawrence believes that accurate representation in media will remove a major burden.

“Erasing, mocking [and] misrepresenting our identity … creates a fight that we have to endure in our everyday reality,” she said. “If we were not tokenized in these ways, then we could focus more on who we are and who we want to become rather than having to constantly defend or question who we are in a world that is forced upon us unnatural to our ways of life.”

Similarly, for Bolts, “Black Panther” has inspired her to be unapologetic about having pride in her African roots. Before going to see “Black Panther,” Bolts’ sister and her sister’s boyfriend dressed in traditional African clothing and went out to eat. She says her sister told her dad that everyone was disapprovingly watching them eat. Her father simply responded, “Let them stare.”

Ramos believes that movies need not include superheroes for them to inspire. Instead, they simply need to tell the stories of real people, like Cesar Chavez.

“A real superhero is a real human being that makes a big difference,” Ramos said, “and [he was] a superhero because [he] was able to change the living conditions of so many people and he was the voice for so many things and advocated for their rights.”

This is not the first time that there has been hope for a shift in media — in 2011, the huge commercial success of the female-led comedy “Bridesmaids” left many holding their breath for major change that did not materialize. But this has not stopped many from hoping that this time will be different — that Hollywood, an industry that pedals in the insubstantial, may be doing something significant.