Inside BSU’s campaign against the N-word

By Alexa Pilgrim

The Black Student Union is holding a campaign to change one of the most common example of hate speech on campus — the use of the n-word.

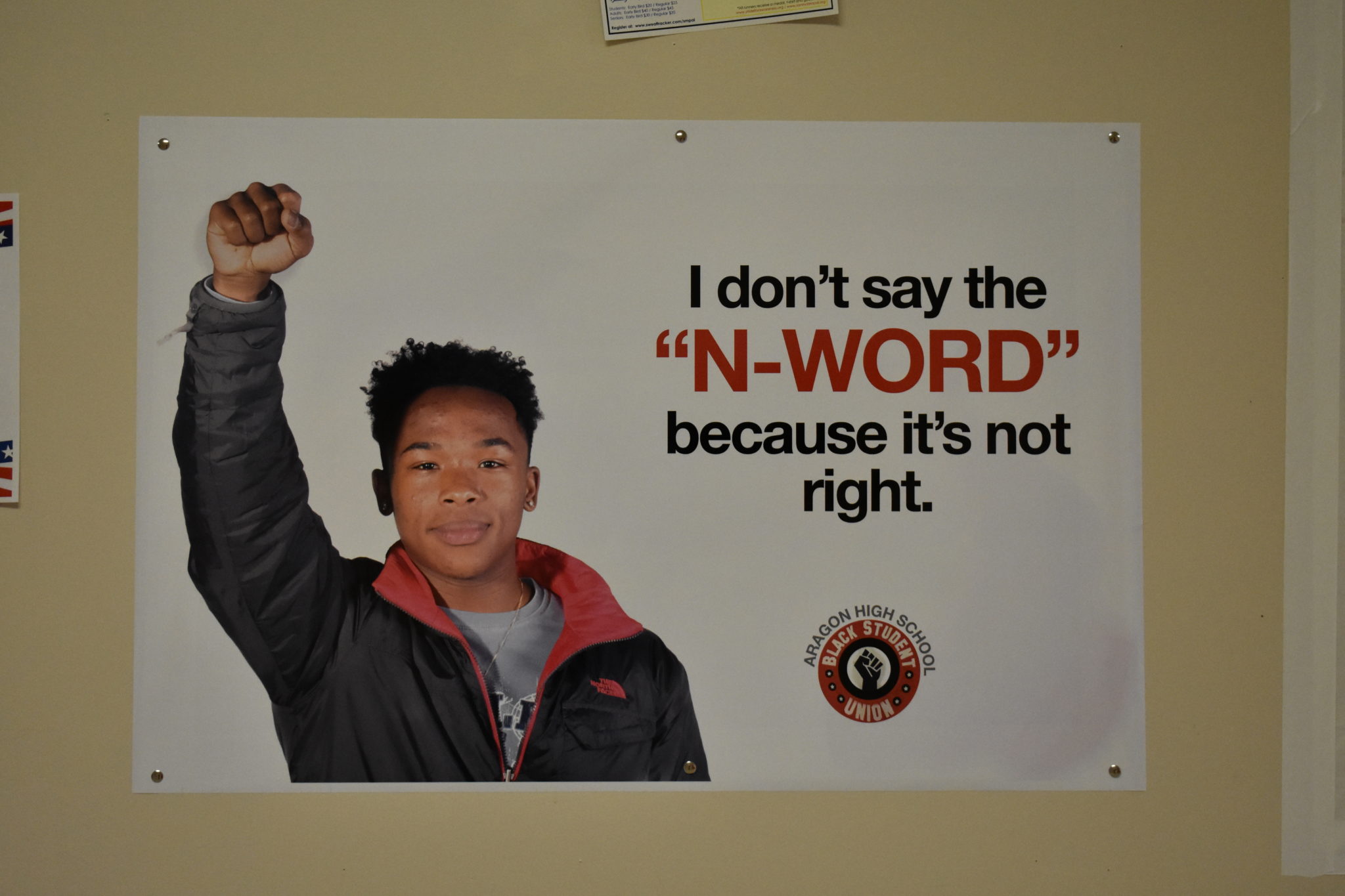

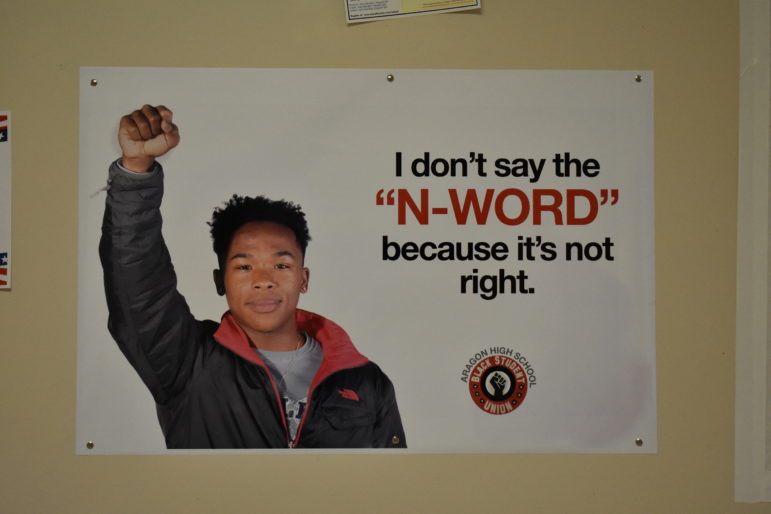

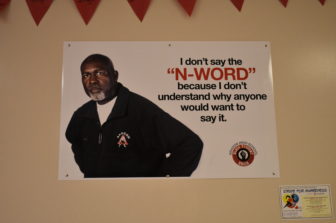

On April 16 and 17, students signed a poster in Center Court, pledging to not say the n-word and received a pin for their signatures. Additionally, posters featuring BSU members were hung around campus.

“BSU came up with an idea,” said BSU member and senior Myles Curry. “And we put it in the live announcements first, about why other people shouldn’t say it, and then we took it a little further and we started coming up with slogans and we put the slogans on the posters, like around campus, and we took pictures for the posters to make it more personal and serious.”

One of the first people to instigate change in the community was senior and BSU co-president Sydney Jackson. She moved from Philadelphia, and was surprised to see the use of the N-word on campus since it wasn’t prevalent at all in her old school among non-African Americans.

“Any other big city I’ve been to where there’s a large African-American community people just know you don’t say [it],” Jackson said. “And if you do, your safety’s being threatened — someone could jump you or something like that but because there’s not a large African-American community [here] people just didn’t know.”

The idea for change was being developed behind the scenes for a while before BSU was ready to launch anything, because they wanted to gather the support of other teachers and the administration to make the campaign as effective as possible.

“Mr. Carrillo and Mr. Bravo both wanted to help us make this into a whole campaign like they did with GSA and ‘that’s so gay’ a couple years ago,” Jackson said. “So that’s how we kind of, with the help of administration, that’s how we kind of started it into a campaign and not just an idea.”

It’s been a week since the posters were put up, but Curry has still noticed an impact on campus.

“I think the posters are more effective than the video announcements,” Curry said. “Because people are seeing them every day and I guess they could feel guilty if they say it and then look at a poster and think, ‘Aw man, I probably shouldn’t be saying that.’”

Despite support by teachers, faculty and students, some are resistant to BSU’s efforts.

“A student posted the n-word multiple times on his Snapchat in multiple different fonts and then he added ‘BSU,’” Jackson said. “We’ve had people come up to the [signing] table and be like ‘Well, why does this matter?’ We’ve had kids in other classes be like, ‘This is not even an issue, why did they bring it up and get all offended about it?’”

Jackson and Curry both recognize that change takes time, but it needs to start somewhere, and they hope the campaign will continue and get even bigger.

“I think if people made more of a big deal of other people saying it,” Curry said. “If somebody hears someone saying it and they go up and say, ‘Oh yeah don’t use that word,’ then I think more people will feel guilty about saying it.”

BSU’s goal to educate members of the community about why the n-word shouldn’t be said has had a far reach, and the campaign is projected to continue growing in the coming month.

Aragon reflects on hate speech

By Naomi Vanderlip

A word is causally tossed around the campus. People laugh about it with their friends or sing along to the lyrics they hear on the radio. Although to some it seems minor and trivial, they fail to notice the effect it has on others. The language is accompanied by a sense of unease and hurt that passes unnoticed. It’s termed “hate speech,” and many students have noticed its presence on campus, and demand there to be change.

Definitions for hate speech can be vague. There is no legal definition, but it’s generally agreed that anything that verbally “attacks a person or group on the basis of attributes such as race, religion, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, disability or gender” is hate speech. Or, as junior Jayla Stokesberry defined it, “Derogatory language towards a person’s identity about things that they can’t control, like their race or sexuality.”

Assistant Principal Lisa Warnke doesn’t think hate speech is a problem specific to Aragon.

“I’ve worked at seven different schools, and there’s always some issues and there’s always times where people find it easier to be negative and bring others down than focus on the positive,” Warnke said, “and that’s across our culture, not just in school. So it’s not something I expected out of Aragon, but I think it’s something that’s just sadly endemic in our culture.”

Senior Eliana Grant first encountered hate speech in middle school.

“This person called me the n-word,” Grant said, “and I won’t tell you how I reacted, but I reacted very negatively.”

Hate speech can create a hostile environment, making targeted students feel uncomfortable and unsafe.

“I think it makes [the environment] less trusting,” Grant said. “I think it makes it harder for you to come and do your job as a student because you’re constantly looking over your shoulder and struggling on talking to your peers. It makes communicating difficult.”

Black Student Union adviser Don Bush believes that hate speech can also hinder students’ learning.

“As teachers, you have to recognize … how much is a student going to learn in class if you’re really thinking about what [another] student next time is going to say about them,” Bush said.

At the same time, Bush points out that a few students saying hurtful language can make a big impact.

“I think most people understand what is appropriate and what is not, but all it takes is a few people,” Bush said. “All it takes is one person to hear something, then it doesn’t matter what the other 1,500 students say. If you hear it from one person, that affects you.”

“It makes it harder for you to come and do your job as a student because you’re constantly looking over your shoulder and struggling on talking to your peers.”

While hate speech may not be seen as serious by some individuals, it does impact the student body. Not only does it create a less trusting educational environment, but it furthers hate speech usage by those who are ignorant to the meaning and history. It’s important to check what is being said and hold people accountable for their words in order to stop the spread of hate speech.

To combat the use of the n- word on campus, BSU is running a campaign to have students pledge to not say it.

“You need to educate people on why you shouldn’t use it and also call out your friends for using it because if your friends don’t think it bothers you, then they can’t change,” Grant said. They’ll just think everything is OK.”

In order for people to change and realize the gravity of their words, Warnke suggests that student advocacy play a large role.

“I think it’s a whole school’s responsibility, not just the administration,” she said. ”And I think that the fact that many of the students are bringing it to the administration’s attention and taking a lead on this is a much more powerful thing than me, the adult, telling students what to do and how to speak. When it comes from your peers, it means so much more.”

Bush talks about the need for school-wide action to be taken.

“I remember 10 [or] 12 years ago when I did hear [‘Oh, that’s gay’] a lot … the GSA had a really good campaign and they made it a campus wide event, where they said that ‘This language is not cool,’ and over the years it’s pretty much gone away,” he said. “I don’t hear that anymore, and I think something similar to that has to happen. There needs to be campus-widerecognition. BSU was working on an action that will hopefully bring it to everyone’s attention that this [using hateful language, like the n-word] is not acceptable.” And so they did, by launching their campaign recently.