The Harvard admissions case drew to a close on Nov. 2, although the judge has yet to issue a ruling. The civil-rights lawsuit began in 2014, when the plaintiff, Students for Fair Admissions, accused Harvard of discriminating against Asian-American students in favor of other minority groups and whites.

According to National Public Radio, “Asian-American males living in rural states need to score a 1370 on the PSAT to get [an informative] letter. White males, however, only need a 1310.”

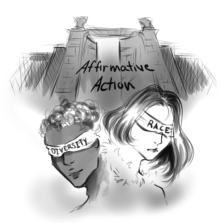

As more admission statistics have emerged, many concluded it is more difficult for Asian-American applicants to be accepted into the University than their white, Latino and African-American counterparts. Students for Fair Admissions attribute this apparent partiality to affirmative action, which has favored underrepresented minorities in higher education admissions for decades to ensure that the campuses remain diverse.

Previously decided Supreme Court cases have banned the use of racial quotas in admissions practices, but allow race to be a consideration on the basis of that a diverse student body is better for the education of all.

However, Students for Fair Admissions believes affirmative action comes at the cost of admitting Asian students.

According to Students for Fair Admissions, the Harvard admissions department uses a “personal factor” to rate its applicants. In top academic applicants, only 17 percent of Asian-Americans scored well in this category, while 41 percent of African-Americans received a good rating.

Chemistry teacher and Dartmouth graduate Michael Wu believes that the requirement to disclose race on college applications is inherently divisive.

“Looking back [on my applications], it’s like, why are they categorizing me based off of a social construct?” Wu said, “What’s the point of that? Why are they asking me for my parents’ household income? It’s one of those things where by asking for [it] you kind of show your hand because if it really didn’t matter, why are you asking?”

“Why are they categorizing me based off of a social construct? What’s the point of that?”

History teacher Jayson Estassi attended Harvard Graduate School and believes another issue to be addressed in universities is legacy admissions.

“The case in one sense has revealed some of the ugly truths about college admissions … in relation to legacy admissions,” Estassi said. “It’s like the dirty secret of higher education. We like to think of [college admissions] as egalitarian, but it’s not egalitarian right? If your parent went there you have a much higher chance; if you’re a donor [you have a] much higher chance.”

The Trump administration has showed its support for the Asian plaintiffs in the Harvard Lawsuit.

“There are multiple different possible reasons for Trump’s support,” said junior Grace Gao. “Trump’s whole campaign gives me the impression that he is not the type of person to care about diversity and minority groups. He would be the type of guy to want college admittance based on merit; that’s why [I think] he backs Asians. [I think it’s] not because he like[s] them but because they are the side that is saying ‘good schools should admit good students.’”

In the eyes of junior Erin McElroy, the Harvard case is a slippery slope that may come to affect students opinions about each other as much as it affects their opinions on private universities.

“I think that admissions based on race does create a stigma between students because other students will view [the minority] student as inferior because they will not believe that student deserved the admission,” McElroy said.

However, McElroy regards school diversity as something just as important as racial impartiality.

“Diversity in schools is important to me because school diversity results in workforce diversity, which means young kids of color can see themselves in leadership positions which helps them see themselves as worthy,” she said.

“School diversity results in workforce diversity, which means young kids of color can see themselves in leadership positions”

On the other hand, many Asian students are frustrated with the competition between themselves and their peers that emerges from fewer Asian admissions.

“Being Asian, I have to work harder,” said sophomore Josh Ho. “I’ve heard many stories of Asians having high GPAs, SAT [and] ACT scores … but they didn’t get accepted by the top universities because they were Asian. I think it has a mental toll if they did not get accepted [into] their dream college and they worked two times harder than the people around them.”

However, as Gao sees it, the existence of affirmative action is integral to the college experience.

“As Ivy Leagues stand right now, the philosophy behind their admittance is to take in the most excellent and hardworking students that are most deserving of the admission, as well as those that may benefit from legacy admission,” said Gao. “Without affirmative action, that would just amount to a school full of rich whites and Asians. Affirmative action is then beneficial in two ways: to provide opportunity to those that are less opportunistic early in life, and to better diversify a school and provide a better college experience.”

Many participants in the lawsuit hope that the case will be carried into the Supreme Court. If they take the case, it could mean new laws for affirmative action and race-based admissions across the United States.

Estassi believes that the Harvard case brings up larger issues that no single lawsuit can address on its own.

“What is the role of a university? Is it an equalizer or is it a place where people from upper class go to finishing school and prepare to enter a high society? Should it provide equal access? These are huge, huge questions and no lawsuit or no single issue can begin to address [these questions],” Estassi said. “I don’t think we have a lot of agreement in society about what schooling should do.”