Though women make up 50 percent of moviegoers, the screen they watch doesn’t reflect that equal ratio. Only 24 percent of movies have female protagonists — these characters were three times more likely to be seen in sexual context — and even fewer women are behind the screen. A 2019 report by the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism examined the 100 most popular films each year over the last 12 years and found that only four percent were directed by women. Even worse, of the 46 female directors, only four were African-American, two were Asian, and one was Latina.

According to Columbia University’s Women Film Pioneers Project, in the early 1900s, Hollywood was teeming with female talent producing their own controversial, non-idealistic films. At that time, jobs in the new industry were open to almost anyone, regardless of experience. With women filling roles in front of the lens, many others started joining those behind it, directing, producing, writing and editing films.

During the 1920s, cinema in America experienced a huge shift and turned into a highly commercialized and conventionalized industry. As it became known that filmmaking was lucrative and prestigious, men started competing for jobs at high rates. Women’s roles behind the camera fell, and many became costume designers, make-up artists and decorators. Around this time, the Hays Code was also implemented; the Hays Code was a form of censorship of topics from homosexuality to abortion that were considered taboo, marginalizing many groups of minorities.

Ellie Wen, a Stanford graduate student in the Master of Fine Arts documentary film program, originally wanted to pursue acting, but chose to follow the producing route instead, as it gave her more agency in creativity.

“There’s still a lot of barriers to entry. There’s more things like fellowship and apprentice programs, where you can shadow other directors on TV shows and see how it gets made,” she said. “But I think it’s so messed up that male directors who have never directed an episode get these jobs without ever having to do the apprentice or shadow anybody.”

Though the advents of many social movements have instigated small fixes and improvements towards gender equality, the gender wage gap and under representation is still evident in many parts of society, especially Hollywood. Larger forces and factors, not just gender discrimination, cause this pay gap.

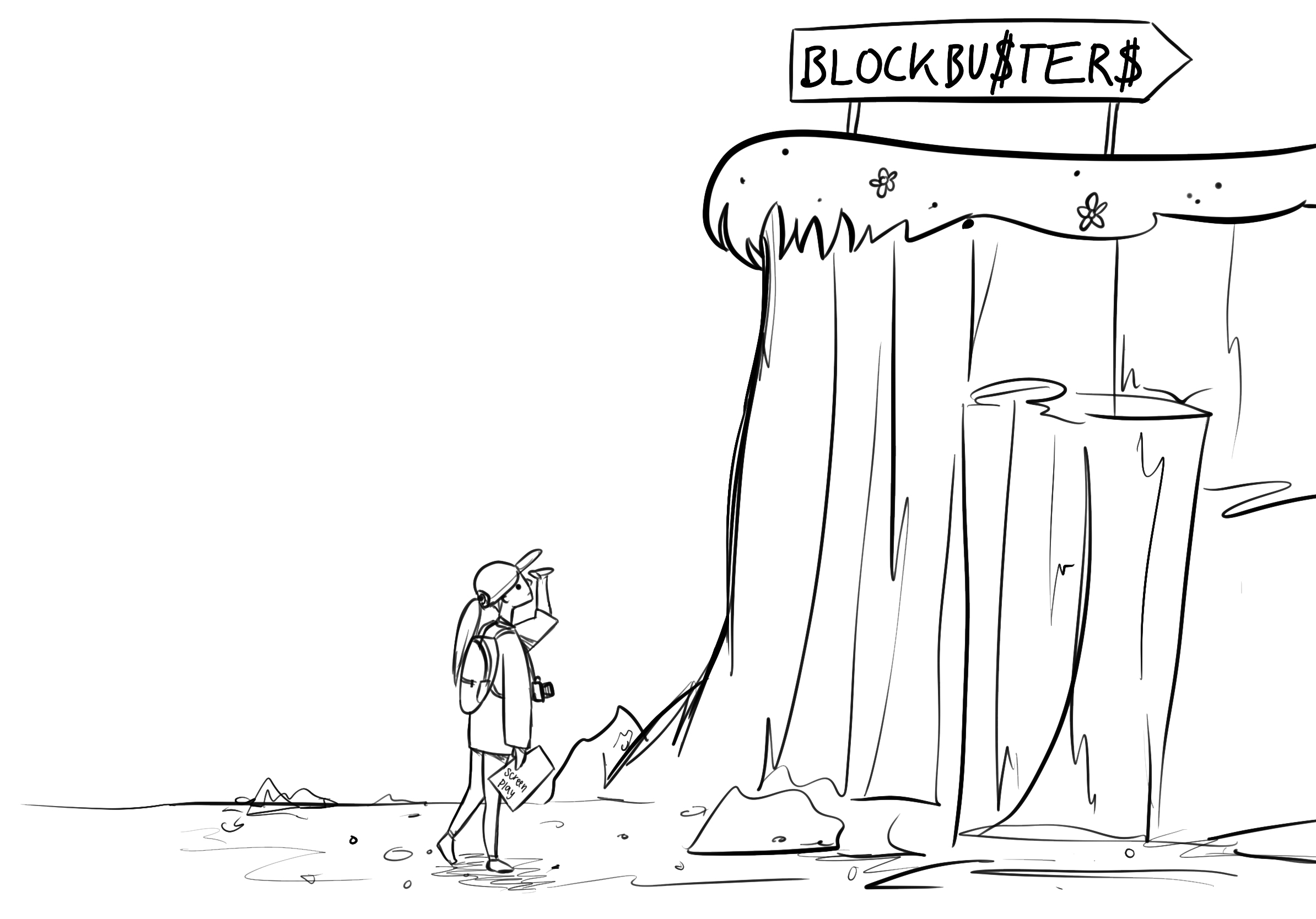

For example, women are more likely to deal with the “fiscal cliff,” which means that they are more likely to stay working on smaller, independent films rather than blockbuster high-budget movies. Since the first Oscars held in 1929, only five females have ever been nominated for best director. Only one, Kathryn Bigelow, won — in 2010 for “The Hurt Locker.”

Though most careers in film start with low budget films, female directors find trouble moving into a position of making narrative feature films, as biases prevent equal access to financing. Women have to face the “cliff” at every stage, which gets steeper as they advance in their careers.

Wen doesn’t attribute this disparity to a lack of qualification, but rather to the perception of women in the industry.

“I still think there’s a perception that women need more help. People need to be aware that there’s these unconscious biases and things, but not necessarily that [women] need more educating.”

At Stanford, Wen’s documentary program is much more gender-balanced.

“In my year, we have four guys and four girls. Actually, I think traditionally, our program has [had] more female admins. I don’t know if it’s a conscious decision, like if [Stanford is] actively trying to do that, or not.”

Statistics show that the documentary film industry is among the closest to gender-balanced in the film world. Women have directed 37 percent of documentary shorts (28 percent in narratives) and 22 percent of the 100 top-grossing documentary directors over the last 12 years. Though higher numbers do persist in this field, there are still disparities in female employment in the narrative film areas.

To combat this problem, along with the Time’s Up movement, many celebrities have been advocating for change to reach 50-50 in Hollywood’s gender distribution.

During her acceptance speech for the Golden Globe award for Best Performance by a Supporting Actress in a Motion Picture, Regina King said, “I’m going to use my platform right now to say that in the next two years, everything I produce is 50 percent women,” King said, “and I challenge anyone that’s out there who is in a position of power, not just in our industry, all industries, I challenge you to challenge yourselves and stand with us in solidarity and do the same.”

It has been shown that movies with at least one female director are more likely to employ a diverse cast. In films with at least one female director and or writer, women comprised 45 percent of protagonists, 48 percent of major characters and 42 percent of all speaking characters. On the other hand, films with exclusively male directors and/or writers, females only accounted for 20 percent of protagonists, 33 percent of major characters and 32 percent of all speaking characters.

“Some of my more fondest memories [are] when I have a really great female crew, and it does make a difference,” said Naomi Ko, an award-winning writer, actor, filmmaker and producer. “The art that is produced that comes out of that is different. It’s fresh, it’s thoughtful, [and] it’s insightful.”

Wen, similar to King and many other female directors pushing for change in Hollywood, is driven by diversity in storytelling.

“When I was working more on the studio executive side, I was really passionate about putting … diverse storytellers in positions.” Wen said.

To young girls thinking of pursuing a job in the industry, Ko believes confidence is key.

“I just hope that girls can approach filmmaking the way white boys can approach filmmaking.” Ko said.

“I think that’s what makes a young girl ready to go through the sometimes very disheartening and truthful process to becoming a filmmaker and having your work produced, but to also have that kind of blind ambition and attitude that you can do it.”