Written by Grace Xia and Anoush Torounian.

Third Avenue in downtown San Mateo has long been a popular after-school destination for Aragon students. But 70 years earlier on this same street, Claire Mack, the first Black Mayor of San Mateo (1991-2004), 84-year resident of Central San Mateo and proud owner of Claire’s Crunch Cakes, saw a large red sign boasting brand new homes with no down payment for soldiers. However, one important word sat at the bottom of the sign: restricted.

“Restricted meant that if you had served in [the military], and your skin wasn’t white, you were not going to be able to buy a home there,” Mack said to The Outlook.

When Mack’s husband returned home after fighting for freedom, he wasn’t hailed as an honorable veteran. Instead, he and his wife, law abiding Black citizens, were denied housing.

“This man had just come home from Korea,” Mack said. “He had been on the front lines. … He came home, and banks didn’t want to give us a loan to buy the house that we live in right now.”

After the U.S. economy’s devastation during the Great Depression, the government sought to increase homeownership by creating the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in 1933 to pay for mortgage debt that had accumulated during the economic downfall. However, the HOLC had to decide which neighborhoods would be favorable investments and which would not be. One aspect they took into consideration was the non-white population of the area. Communities with greater minority populations, such as Oakland, were deemed “hazardous” and less worthy of receiving investments. These neighborhoods were shaded red on maps, which led to the coining of the term “redlining” to describe discriminatory practices that prevented residents of certain locations from receiving services or resources.

“There [are] still a lot of cities with high levels of segregation, [and] a lot of households have been displaced … because of the cost”

Mack’s encounters with redlining extended beyond her personal experiences. In the 1950s, her Black friend’s family struggled to purchase a home in San Mateo Park.

“This family had to buy their home by getting a white person to go to buy the house [first],” Mack said. “They had the money. They [owned] several houses around this neighborhood. Their family had owned a restaurant, but they couldn’t buy this house just by going to a real estate office. … They couldn’t do that right here in San Mateo, California.”

While the Federal Housing Act of 1968 prohibits discrimination in housing, neighborhoods remain socially stratified as a result of previous laws. De facto segregation, the separation of groups based on corporations’ policies or individuals’ choices, continue to prevent integration of ethnic groups today.

“Redlining occurred so long ago, but it’s the kind of evil that has been attached to the people that it was attacking; it has followed them for generations,” said Tim Thomas, research director of The Urban Displacement Project, a University of California, Berkeley research and action initiative, to The Outlook. “We’re not dealing with Jim Crow right now, but we’re dealing with evictions amongst Black households.”

Thomas’ 2013 dissertation, “Forced Out: Race, Market, and Neighborhood Dynamics of Evictions,” reveals that Black women were being evicted seven times more than their non-Black counterparts in King County, Seattle. His research has since helped change laws in Washington state.

In line with Thomas’ work, the Legal Aid Society of San Mateo County aims to protect marginalized and low-income people from afflictions like eviction, a byproduct of discriminatory practices such as redlining.

“We always [represent] a large number of people of color … who are living below the poverty line,” said David Carducci, an eviction lawyer at the nonprofit.

The Bay Area is home to intense racial and economic divisions. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, out of 100 regions in the country, San Francisco ranks No. 84 for economic inclusion. Stratified communities leave little room for communal understanding among people of varying socioeconomic status.

“One of the biggest issues that white individuals tend to face is that they don’t know the experiences of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) individuals because they just cluster with [their own ethnic groups] and benefit from privilege,” Thomas said.

During her time as mayor, Mack discouraged policies that prevented integration of communities.

“Anytime you build an apartment over ten units, 10% of your units need to be low income, or affordable income,” Mack said. “There’s a move afoot through San Mateo just to get rid of that. I don’t believe in building ghettos.”

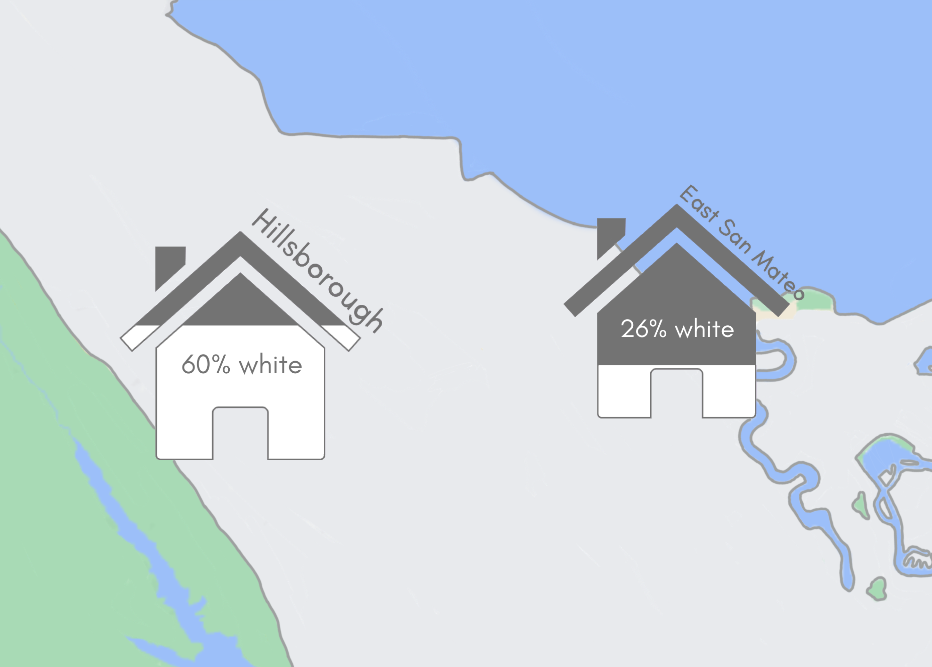

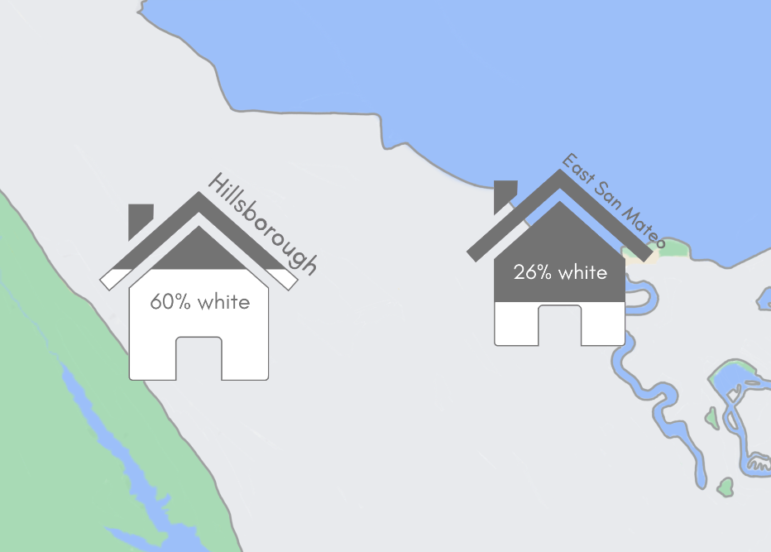

The most affluent parts of San Mateo County are overwhelmingly white. Hillsborough, for instance, boasts a $4.6 million median property value and a $440,000 average annual household income. Its population is 60% white. Drive six miles from Hillsborough to East San Mateo, where 36% of the population is Hispanic or Latinx, the average house is worth $866,000, the median household income is $115,000 and the poverty rate is over four times higher than in Hillsborough.

Aragon’s student body, which consists mostly of residents from San Mateo, reflects the socioeconomic disparities seen across the city. A former Aragon student, senior Gloria Carrabino, who moved to Manteca due to the rising cost of rent at her old San Mateo home, recounted her time here.

“I’d always feel so different [from my friends] … because of the income difference,” Carrabino said. “You would see all the kids coming from the neighborhoods right in front of Aragon and Hillsborough. Me and my brother, we’d have to take the bus all the way over to Aragon from our neighborhood, and then we’d see all the kids with their cars … driving Teslas.”

Carrabino’s mother worked at a grocery store and her father took on two jobs, one at a golf course and the other in produce. However, this three-income household could not combat the city’s high costs of living.

“I really did not want to move, but … our landlord kept raising rent,” Carrabino said. “[One day] he just came to our house screaming at my dad about raising our rent [again].”

While some landlords believe that their evictees can find new homes, this is not the case for many of Carducci’s clients.

“Low income tenants aren’t so much going to be able to rebound,” Carducci said. “They’re going to have to survive … before they can be self-sustaining again.”

To escape inflated prices, Oceana High School senior Nicolas Nelson, who is Brazilian and white, is moving to Idaho after he graduates from high school. Nelson has witnessed the gentrification of his neighborhood, a mobile home community he has called home since childhood.

“[The community] used to be pretty affordable,” Nelson said. “A lot of the houses [that] are older and rundown are getting taken out, but those … more modern looking [or] new ones are expensive to buy and rent.”

As living costs surge, forcing different groups of people into new areas and allowing new, wealthier buyers to move into emptied spaces, the demographics of communities have shifted accordingly.

“We’re entering an era where segregation is flipping,” Thomas said. “There [are] still a lot of cities with high levels of segregation, but a lot of households have been displaced or pushed out of the Bay Area because of the cost or other reasons, leading to … what we see as diversity. Eventually, what’s happening is [a] replacement of people.”

“This family had to buy their home by getting a white person to go to buy the house [first]”

The soaring cost of living in the Bay Area prevents people from choosing their home location, but it’s not the only cause. Thomas described the four primary theories of segregation in modern neighborhoods: preference, economics, discrimination and networks.

“Everyone has free opportunity to move to any neighborhood they want to, but there has to be a home available to them, it has to be affordable, has to be a place they prefer … where they’re not being discriminated against,” Thomas said. “Finally, they [have to be] aware of the dimensions of what they’re getting into. … You tend to cluster with certain similar types of people … [and] want to stay closer to kin or people that are of your community.”

In tandem with housing limitations are underfunded education systems. According to Edbuild, a nonprofit that focuses on education funding, school districts with a majority of students of color in their enrollment receive $23 billion less in yearly education funding than predominantly white school districts, despite serving the same number of students.

“There [are] high property taxes [near Aragon], and the people who live near there have a lot of money,” Nelson said. “That’s what drives a lot of schools being developed and [having] great education and sports [programs].”

California’s Local Control Funding Formula, enacted in 2013, distributes a certain amount of money to schools with a higher proportion of underprivileged groups like English learners and low-income students. While this measure is a stride for socioeconomic equality, if a school’s local property taxes exceed a value specified in the LCFF, like Aragon, it can allocate more money than underprivileged schools to provide resources for its students.

Extending past Aragon, the San Mateo Union High School District’s revenue for the 2020-2021 school year totals at $166 million for over 9,000 students across eight different schools, while the Jefferson Union High School District’s revenue comes in at $64 million for nearly 5,000 students across five schools, including Oceana.

“Jefferson Union High School District is [less funded than SMUHSD] … because of the amount of people who live here who can barely live here,” Nelson said.

The new finding from Edbuild calls into question the ways state and local dollars are used to prop up some children at the expense of others, exposing a similarly startling funding discrepancy even when comparing poor white and poor nonwhite school districts. Carrabino has noticed a sharp difference in funding between Aragon and Sierra High School.

“[At Sierra], we can’t just buy ourselves a new football field or a massive theatre,” Carrabino said. “We really have to put [the money] into helping students with having resources for education that they wouldn’t normally have access to, especially during times like this.”

Manteca Unified School District has a total revenue of $256 million across its 30 schools for around 24,000 students, 56% of whom are Hispanic, according to data from 2019. Half of the schools in this district are rated below average for school quality. With an average spending per student significantly lower than that of the SMUHSD, the MUSD is one example of the way in which poorer areas receive fewer educational benefits than students in wealthier areas, contributing to more economic instability within families.

The costs of living contribute to a lack of social mobility in housing — some people barely have enough money to survive, much less relocate to a more affluent part of the Bay. While housing costs drive people out of expensive neighborhoods, the prospect of a home increasing in value overtime keeps homeowners from leaving.

Although San Mateo has made headway from its days of redlining, current socioeconomic divisions won’t be easily erased. However, Mack’s neighborhood, which she admiringly describes to be a flourishing community with people from China to Bangladesh to Black residents like herself, serves as proof that diversity is on the horizon.

“Let’s build equality into our countries, into our communities,” Mack said. “Let’s make this a place where you can live equally. Just because you have more money than me, because you’re the banker or because you own Facebook, doesn’t mean you’re a nicer person. It doesn’t mean you’re a better person. You’re just a person that’s got a bigger bank account.”