During the pandemic, Aragon has experienced a sharp decline in substitutes. This issue has occurred nationwide, in some cases forcing students to take time off from school. In Seattle, schools are closing. Some students in Colorado are returning to remote learning, and others in Michigan had a week off from class.

“Last year, before online learning, I had about 145 [substitutes],” said San Mateo Union High School District Human Resource generalist Sandra Fewer. “This year, I [only] have 80.”

Particularly for older substitutes, teaching has become a health concern in the face of COVID-19.

“I attribute [the substitute teacher shortage] to COVID-19 fears and concerns,” said substitute teacher Rita Deiz. “[A] lot of the substitute teachers are retired teachers, or they’re older, [so] they’re more susceptible if they do get COVID-19 and their immune systems are not as strong.”

Worried she could spread the virus to her family, Deiz was initially hesitant to come back. However, upon seeing strict COVID-19 protocols and safety measures, Deiz felt comfortable returning to school campuses.

“My mother is in her 90s, [so] I visit her as often as possible,” Deiz said. “I certainly want to make sure I keep her safe by not exposing myself to people. I do feel safe now. Not only am I vaccinated, [but] I’ve received a booster … and I get notifications of cases in the school district.”

The substitute teacher shortage contributes to the broad economic trend of people across the country rejecting certain jobs and not wanting to work during the pandemic.

“I actually started my career as a substitute teacher. At that time, I couldn’t even get on the sub list”

“On the news we see every day … how Americans are quitting in record numbers,” said history teacher Jayson Estassi. “Americans are increasingly saying no to jobs that don’t have particularly favorable working conditions. I actually started my career as a substitute teacher. At that time, I couldn’t even get on the sub list in this district. For the right person, subbing can be a good job, but it doesn’t offer any benefits. The pay is okay, but in this area, it’s hard to make a living.”

However, some experienced substitutes feel that the substitute shortage is a persistent phenomenon that isn’t entirely caused by COVID-19. Estassi agrees and says that substitute teachers are often put into difficult situations with little warning, resources or guidance.

“When I was starting off, I got asked to sub [periods] zero through seven,” Estassi said. “[Another time], there were two classes, [and] they put two classes together [in] one classroom. I didn’t know whose lesson plan I was supposed to follow. There weren’t enough desks. The secretaries [at the school] said [students would] have to sit on the floor.”

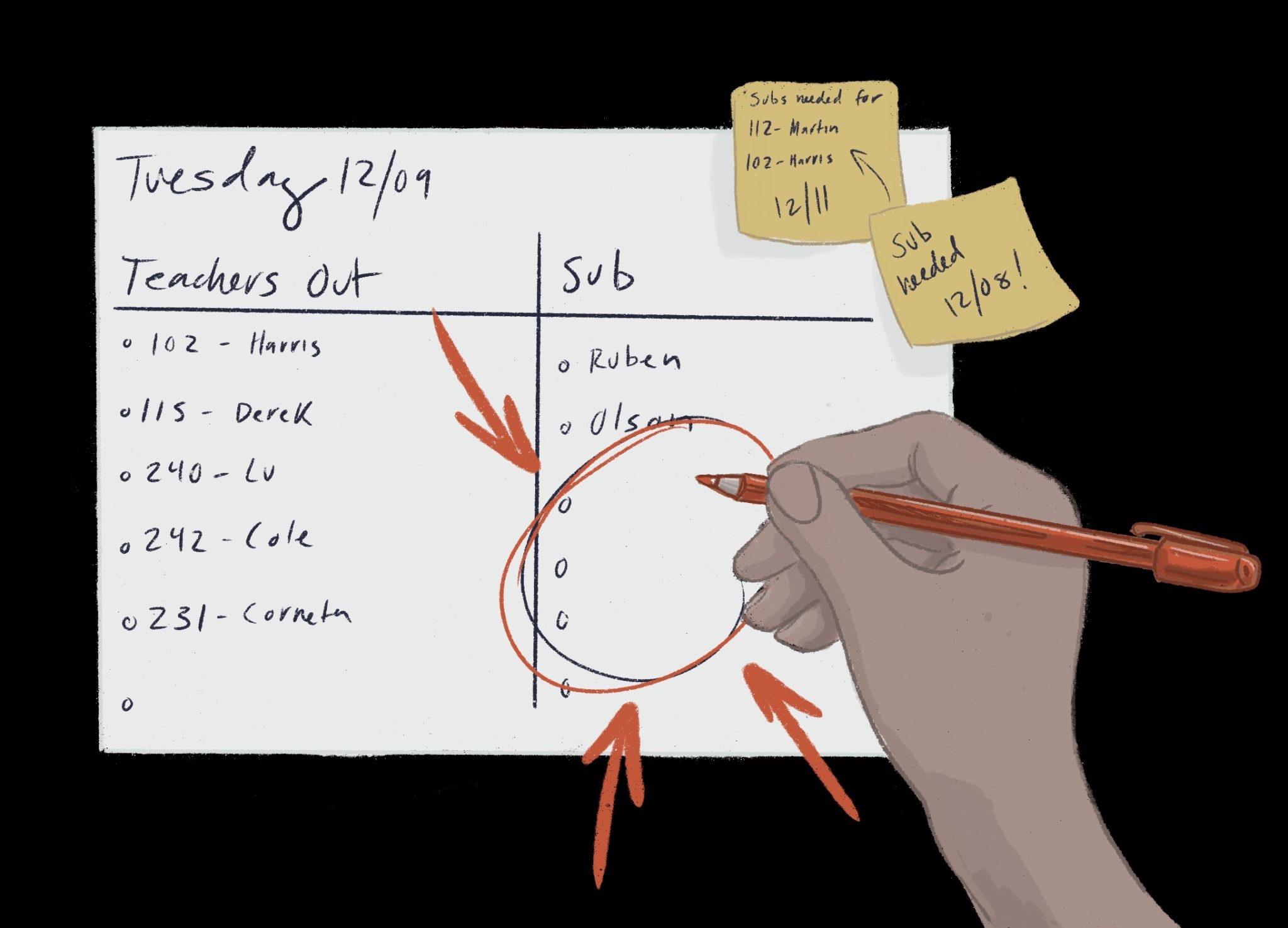

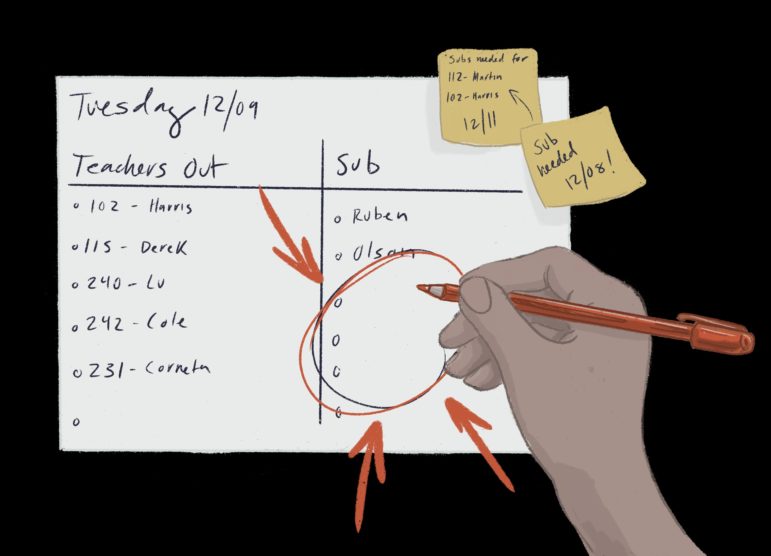

As the substitute shortage worsens, teachers can be called to fill in gaps for their colleagues with little to no notice. Administrative assistant and general office counselor Becky Foster coordinates the school’s substitutes.

“A third of our openings would be covered by Aragon teachers,” Foster said.

“We hired a few [of] what we call full-time floating subs … [who are] available to work every day”

English teacher Holly Estrada, who teaches full time at Aragon, also has experience being a substitute teacher. She describes the difficulty of subbing for absent teachers, especially when she is given little notice.

“[It’s] terrifying,” Estrada said. “You don’t feel in control [and] you don’t know who the kids are. Sometimes, if you’re in your own class and something doesn’t work, you can scramble and try to come up with something. But [when you’re a sub] you could walk in the room and not be able to find the plan to get the technology to work or get the DVD to play.”

The substitute shortage, however, does not only affect teachers and staff. Often, students are disoriented by the chaos surrounding finding substitutes.

“If a substitute isn’t given [enough] time to prepare, it feels like they are trying to figure out the lesson just as much as we are,” said senior Ellen Grey.

The district administration is working to fix the substitute crisis by offering incentives and increasing the substitute teacher pool.

“On Oct. 1, we increased our pay for the substitutes by 15%,” Fewer said. “We hired a few [of] what we call full-time floating subs, meaning that they’re available to work every day. We [are] also [trying] to tap into our student teaching population. While they’re going to school [and] teaching students, we try to get them to get a sub permit [so] they can help [out] at their school site.”

So far, the administration and the District have been able to keep the substitute shortage under control and minimize the impact on Aragon students.