Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the ever-present racial and socioeconomic disparities in healthcare have been clearer than ever.

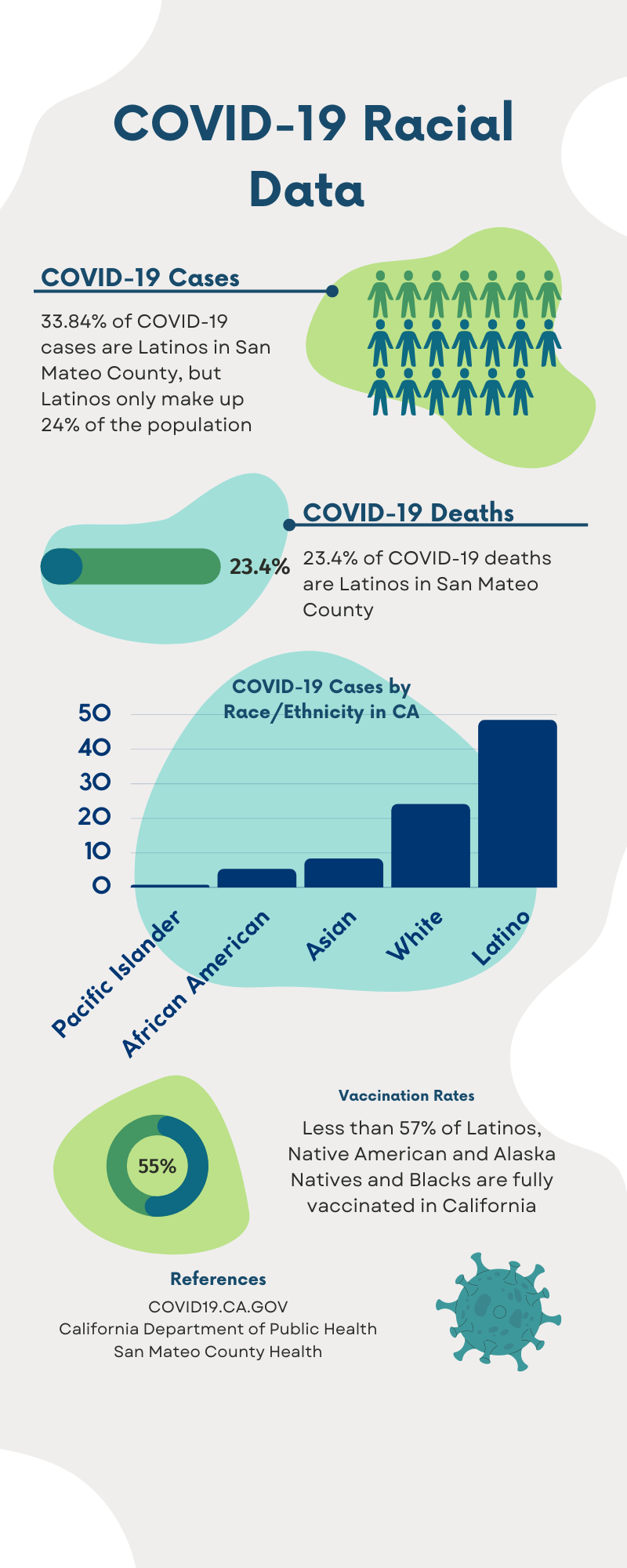

Over the past two years, more Latinos have contracted COVID-19 and died from the virus than any other ethnic group in California. According to the California Department of Public Health, as of Jan. 26, almost twice as many Latinos have contracted COVID-19 as whites, the next most infected group.

“In epidemics and pandemics like these, the most affected are the marginalized communities, the people that have no resources or people that have been systematically excluded,” said Dr. Jesus Ramirez-Valles, the director of the Health Equity Institute at San Francisco State University.

While Latinos make up 38.9% of California’s population, they make up 45% of the total COVID-19 deaths. Although the death rate of Latinos is lower than that of whites, this may result from age differences between the Latino and white population. Older people are more susceptible to COVID-19, and, according to the California Department of Finance’s 2017 American Community Survey, nearly 60% of California’s elderly population is white.

According to the state’s COVID-19 dashboard, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders are the ethnic group with the highest full vaccination rate in California at 96%. Less than 57% of Latinos, Native Americans and Alaska Natives and Blacks are vaccinated.

Income also may contribute to vaccination rates. According to California Health Department Data from Dec. 28, 2020 to Sept. 28, 2021, zip codes with higher poverty rates had significantly lower vaccination rates.

“Unfortunately, the impacts of COVID-19 and the pandemic are tied to socio- economic status,” said senior Grace Bloch. “This draws back to who your family is, and the different resources that are available to you.”

Vaccine access also posed another major issue in California. When vaccinations began, clinics were sparsely available and many were concentrated in affluent areas.

“When we first started doing immunizations, we would see people coming [115 miles] from Sacramento to get their vaccines, just because that’s the closest place that they could get vaccinated,” said Aida Vakili, a pharmacy manager in Half Moon Bay.

Beyond that, the nation’s history of exploiting minorities has led to a general dis- trust from communities that have been taken advantage of, leading to vaccine hesitancy.

“[Minorities] have been exploited by the medical field in the past,” Ramirez-Valles said. “African Americans, Latinx people [and] Native Americans [were subject to] nonconsensual [sterilization] … [or used] to try out medicines.”

Disparities were also present in regional COVID-19 data. According to data from San Mateo County’s COVID-19 dashboard, as of Jan. 31, 33% of those infected with COVID-19 were Latino, while census data shows that Latinos need it for traveling.” Anecdotal evidence also suggests there was less vac- cine hesitancy in the Bay Area. If anything, inequitable vaccine access was the problem.

“There wasn’t much hesitancy,” Vakili said. “When we started doing boosters, it was initially for [the] immunocompromised, but … people were lying that they were [eligible].”

Aragon and District administrations have hosted vaccine clinics and testing sites at schools, offering resources to those who lack access otherwise.

However, for those who tested positive, levels of support varied. Sophomore Nolan Rivera and his family came in contact with COVID-19 on Christmas Eve.

“The district provided us with rapid tests, and we were able to get PCR tested,” Rivera said. “It took a lot of stress off our family and … made us feel a lot safer about everything.”

In contrast, sophomore Lia Moynihan had to purchase her own tests after testing positive.

“I was on my own,” Moynihan said. “The District helped a lot with the weekly testing but I didn’t receive any support while positive. … There was a limit on how [many COVID-19 test kits] we could purchase. I think it’s unfair to only [allow us to] purchase two at a time for a family of three.”

Similarly, sophomore Gabrielle Hernandez’s family struggled to find COVID-19 tests.

“[When] my parents tried to get a COVID test [kit], the shelves were empty,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez and her family live with her elderly, high- risk grandmother, so they had to be especially careful about quarantining.

“It really divided our family because … we’re all very affectionate,” Hernandez said. “I couldn’t give my grandma a hug … just in case she would get sick.”

While disparities impact different communities in different ways, COVID-19 has clearly illustrated the racial and socioeconomic inequalities present in the U.S. health- care system and the nation as a whole.