School textbooks are adopted to supplement a class curriculum and are where the bulk of the information is consolidated. Although enhancing the quality of textbooks through updates is necessary to keep the material reliable and helpful to students, switching textbooks too frequently can lead to environmental and financial issues. Replacements should only be implemented in cases where students’ understanding of the material would be significantly impacted. The editors of The Aragon Outlook urge the San Mateo Union High School District to continue making textbook replacement decisions wisely by considering how replacements would impact students to help avoid wasting money and paper.

The main purpose of textbook turnovers is to replace outdated or inaccurate textbooks with new versions to add updates and new information. Since textbook decisions are districtwide, the District sends out a request to major textbook publishers that would send whatever books are relevant to the particular subject. The decision is narrowed down by a group of department chairs, with one or two teachers from each school. After the chosen textbooks are offered to teachers and piloted, the group receives feedback and finally selects a textbook that the

Board approves.

“The College Board puts out a list

of approved textbooks, so [it’s an]

easier process to pick [them]”

AP textbook selection, however, is different and more pressured in order for the courses to meet AP Course

Audit resource requirements.

“Because the College Board puts out a list of approved textbooks, [it’s a] much easier process because you just kind of pick from a list,” said U.S. Government and Economics and AP Psychology teacher Giancarlo Corti. “[College Board has] an expectation that the textbooks or at least the material covered in class are up to date. So if a district can-

not afford to keep updating textbooks, they just expect that the material that you use in class may need to be changed or updated to reflect new understandings.”

It is important to acknowledge that textbooks are not the sole resource. Textbooks are usually used as a way to provide background information for students, who will come to lectures prepared.

“The AP Gov exam is really only

looking for a couple of things that

are in the modern era”

“[I tell AP students to] read the chapter on the judiciary, so I know when you read that you have the basis of the judiciary,” said AP Government and Politics teacher Kevin Nelson. “And then when you see me, you have my lecture outlines and you have all the different stuff that I create on Canvas. [They’re] designed to enhance that [understanding].”

Therefore, in an age where countless resources are available on the internet at the touch of our fingertips, it is unreasonable to constantly depend on textbooks to be updated.

“There’s no way the textbook can keep up with history,” Corti said. “So it’s nice to get them updated because they are worn down or because they are falling apart or because there’s literally incorrect information because it’s been so long. But other than that, no, I don’t find tons of value in a very constant updating of textbooks.”

To an extent, there is value in updating textbooks, but it comes at a cost, and the cost is potentially wasteful. The College Board recommends AP Government and Politics textbooks to be updated every four to five years because the course is connected to the changing modern times. But it is not always necessary to update the new information so often for the sake of following a recommended cycle.

“Since the AP Gov exam is based on … traditional political science methods, they’re really only looking at a couple of things that are in the modern era, whereas most everything that you’ve seen is going to be court cases, legislative pieces, some of the stuff that’s in political behavior,” Nelson said. “[Things] like Canvas [allow us] … to bring all kinds of better up-to-date items into class.”

Money is an important factor to consider in the adoption process. In 2021, the SMUHSD spent approximately $43 thousand on math textbooks and $19 thousand on science textbooks.

“There’s no way the textbook can

keep up with history, so it’s nice to

get them updated”

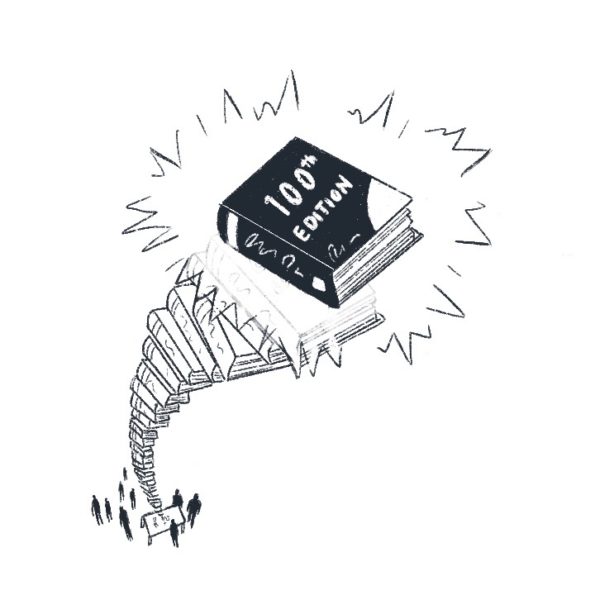

Another factor to consider when replacing textbooks is the paper waste created by new textbooks. According to Aragon librarian Anna Lapid, when textbooks need to be disposed of to make room for new editions, the library staff has to request permission from the school Board. Once the request is approved, the library staff tries to donate the textbooks to countries in need, such as Africa. However, if shipping finances are deemed too expensive or an organization decides that the textbooks have inaccurate information, the school won’t be able to donate them. Instead of being recycled, the replaced textbooks would be thrown into the landfill. The average textbook has well over one thousand pages of content. Once such textbooks are replaced and rendered unusable, an overwhelming amount of paper must be discarded. Moreover, according to the University of Michigan’s sustainability brand Planet Blue, 30 million trees on average are cut each year to make textbooks. In a world where deforestation is a serious problem, it is incredibly important for our district to not take the paper supply for granted and consider whether the potential waste that could be generated for updating textbooks would be worth it.

To save money and paper, the District should carefully determine when certain textbooks need to be replaced. In addition, buying the digital version of textbooks is a solution that could be implemented in the future if the District has a sufficient budget. That way, the paper waste accumulated by the constant cycle of updating textbooks will decrease. As the District continues to provide Chromebooks and hotspots to students, one day, turning to digital textbooks can be more feasible and environmentally friendly.

Textbooks are heavy investments. Therefore, to conserve paper usage and save money, the editors of The Aragon Outlook believe that the District must carefully consider when to replace them instead of strictly following a frequent cycle.