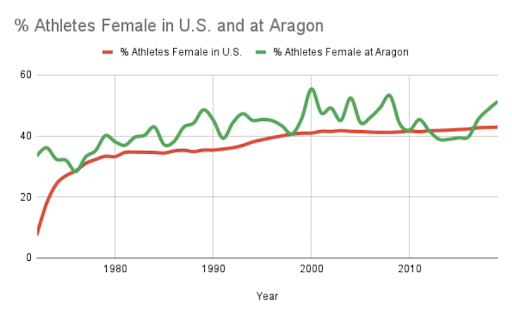

With its 50th anniversary coming up on June 23, Title IX is a law passed under the Nixon administration that forbids sex-based discrimination in any federal government funded activity. It is most famous within the lens of athletics as it kickstarted opportunities for female athletes to compete on the same level as male athletes. Milestones toward equality in sports continue to occur today, such as when assistant coach Alyssa Nakken made Major League Baseball history on April 13 as the first female coach to step onto the field at a San Francisco Giants Game. Change has not only happened in the coaching field. In the 1970s, less than 40% of athletes at Aragon were female. By 2020, that percentage became closer to 50%.

In the process of earning his master’s degree in history, U.S. history teacher Will Colglazier is taking a class centered on childhood in America. He has always been interested in female athletics at Aragon, especially after being the girls soccer coach for six years. As a final project, Colglazier combined his interests in female athletics and history by researching Title IX’s impact on Aragon with the help of yearbooks from the late 1900s.

“Going into [the] books and counting up how many female [and male] athletes plus how many students [there were] in the school so that you can make those percentages was a time-consuming process,” Colglazier said. “I [thought I] might as well engage my students in what a historian’s process might look like, which is sometimes painful research. I bribed them with doughnuts afterwards to say thank you.”

After collecting data on Aragon and the U.S. average, Colglazier created several line graphs, one of which showed Aragon being ahead of the national average percentage of female athletes.

“[The] … law has been more helpful for white suburban girls than girls of color or in urban areas,” Colglazier said. “The fact that we are still beating the national average with a more diverse school population … speaks highly of the culture we have here.”

Even the red banners in the North Gym display the effects of Title IX.

“One thing you can notice [about] these banners [is that] … [the athlete] of the year [award] starts in [1961] for the men, [or] the first year of the school, but for the women, it starts in 1974 and Title IX started in 1972,” Colglazier said. “[They tried to] hide [the gap] with the Don.”

Up until Title IX passed in 1972, female sports were not a part of the San Mateo Union High School District.

The GAA, a volunteer organization, has presence that is prevalent in the archives of The Aragon Aristocrat, which was the former name of Aragon’s student newspaper. Sports headlines in the 1960s and 1970s were divided between those with “GAA” included in them that indicated the article would be about girls athletics, while boys had typical, mainstream sports headlines.

In 1971, a year before Title IX was passed, there were 10 boys and 11 girls teams at Aragon. However, these seemingly equal numbers can be misleading because these girls teams were organized under the GAA rather than the California Interscholastic Federation. Girls teams had to fundraise for uniforms and were not able to compete in events organized under the CIF, such as the Peninsula Athletic League or CCS championships. In 2019, there were 26 boys and 31 girls teams.

P.E. teacher Annette Gennaro-Trimble played basketball at Aragon in the 1980s, when female athletics started to experience some changes.

“One thing I remember about basketball is that they changed the size of the ball,” Gennaro-Trimble said. “That irritated me because … the ball used to be what you call the guy-size ball, [which is] what I used to play with [as point guard]. Then all of a sudden [in] my senior year, they switched to a girls ball [with a] 28.5 [inch] … [circumference], which is one inch smaller.”

When Gennaro-Trimble returned to Aragon in 1992 to coach, a major change in girls basketball was the implementation of the quad system, meaning that junior varsity girls and boys, and varsity girls and boys, played on the same day.

“If you wanted to see the varsity boys game, you got to the game by the halftime of the [preceding] varsity girls game,” Gennaro-Trimble said. “The gyms were packed and doors [were] closed. [The girls] pulled a lot of the [boys] audience. Our girls team back then [was] fabulous. We went to [the] state [championships] two times in a row. That was a part of Title IX, opening those doors [and] recognizing that the women’s game is just as good as the boys.”

“That was a part of Title IX, opening those doors [and] recognizing that the women’s game is just as good as the boys”

The progress is not exclusive to female athletics. Carly DeMarchena became the boys varsity water polo’s head coach in 2017, one of the few female boys water polo coaches, and won the CCS honor coach award last fall.

“Coaching boys was not my original plan,” DeMarchena said. “But I think it’s great. There’s just a couple other female coaches in our league. There’s been times [when] I’ve seen [that] people are surprised that I’m the coach, whether that’s other coaches or referees. I was asked [at] a tournament [if] I was hosting … and I had to clarify [that I was]. I think kind of just as the years go on, [having been] in this league for so long, … you see more and more women taking that role.”

However, others like AP Biology teacher Katherine Ward did not get to experience the same opportunities during their high school years. Ward attended Half Moon Bay High School in the late 1980s.

“[The boys] would have the gym right after school,” Ward said. “We would have the gym late at night, and it didn’t rotate until my junior year or senior year in high school. [It] finally did rotate [because] you can’t keep just making girls go to practice from six to nine.”

The inequalities persisted during her time as a track and field thrower at the University of California, Davis.

[The men’s] throwing coach was actually a specialist in throws,” Ward said. “Our throwing coach was the trainer in charge of conditioning for football. He didn’t know anything about throwing. The men got brand new shoes every year. [We] got the men’s hand-me-downs, [so] they [didn’t] even fit for our feet.’”

During Ward’s time there, the school just started to form Title IX committees.

“[Part] of it was because women started demanding,” Ward said. “They started saying, ‘Hey, look, this is supposed to be equal, and it’s not. It’s not okay that I’m [getting] hand-me-down shoes from the guys last year.’”

P.E. teacher Linda Brown was also a high school student-athlete in the 1980s like Ward, but did not have to face as many inequalities as her.

“When I was in high school, the basketball teams swapped times,” Brown said. “[We] played tennis in the fall and guys played tennis in the spring. We each had softball and baseball fields.”

Nonetheless, inequalities still exist. In 2021, the National Collegiate Athletic Association received backlash after female athletes shared photos of the disparities between the weight rooms at the women’s and men’s basketball tournaments in San Antonio.

“[You] had a men’s setup for training and everything that was supposedly the stellar weight room and women’s was like a tiny room with these tiny weights,” Brown said. “As you get athletic directors that are more aware of everything that’s happening, less of that happens.”

For example, due to his upbringing, Aragon athletic director Steven Sell has always been a feminist.

“I was raised by … Kennedy Democrats … and I think I was instilled [with] … a sense of fairness,” Sell said.

He started as a football coach in the early 1990s. Throughout his career, he has witnessed discrimination against female athletes.

“[Being] a football coach [at the time], I may have been in the minority to think [that] women should have equal access,” Sell said. “I think a lot of people … who were in football were very much against having anything taken away from them.”

Sell attended Aragon in the 1980s and the gyms around his office looked very different back then. The main gym, where the boys played, had bleachers while the other one, where the girls played, had no bleachers and a smaller court.

Attitudes about the competitiveness of girls athletics also varied among people.

“If [someone coaches] a boys team [that] isn’t doing well competitively, people say, ‘Hey, we need to make a coaching change [because] those boys should be winning more,’” Sell said. “Whereas if a girls team is under-achieving, the mindset is, ‘Hey, they’re having fun.’ [But] girls want to compete just as much as boys do.”

Sell emphasized that sex-based discrimination should carry similar weight to race-based discrimination in sports.

“[A coach once told] me that he’s not gonna let a boy wrestle one of our girls [and] you’re gonna have to forfeit,” Sell said. “[But] what if 20 years ago, one of our white wrestlers didn’t want to wrestle a Black kid? [Some would say] that’s different but no. It’s not.”

While Title IX has been a part of scholastic sports for half a century, strides are still being made toward sports equality and equity. The banners in the North Gym demonstrate the reality of the disparities between boys and girls’ sports prior to Title IX, but Title IX’s most important and lasting impact is the number of female athletes today who have been empowered by the programs and funding it mandated.