Detention is a punishment detailed in the student handbook and syllabi of many classes. It is often the answer to dealing with students who have 10 or more unexcused tardies or who repeatedly demonstrate poor behavior. However, its effectiveness may be lower than intended.

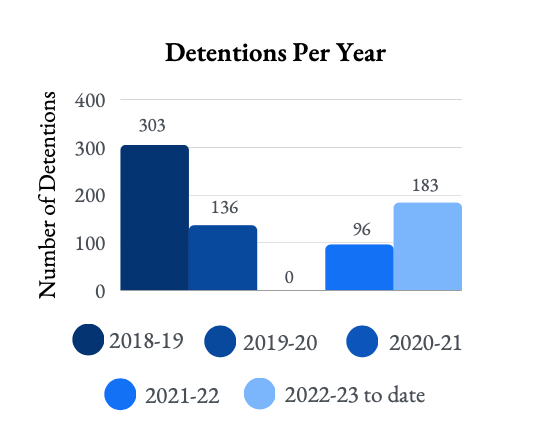

Two years ago, during distance learning, there was no detention. Last year, it returned slowly, with only 96 detentions compared to the 303 detentions of the pre-pandemic 2018-19 school year. In the 2022-23 school year, the 183 detentions within the first 12-week period already surpass last year’s total.

“I see the same kids doing the same thing over and over, so I don’t think [detention is] really working,” said junior Koni Manukainiu.

“I see the same kids doing the same thing over and over”

Staffulty hopes detention will help students think about their actions by assigning them reflection assignments in detention. These tasks include picking an inspirational quote, writing paragraphs about what they did to warrant detention, and showing they can improve this behavior in the future.

“Students need a safe place to go and process … Detention provides [that]”

“Students need a safe place to go and process after they have made poor choices,” said dean of students Donna Krause. “Detention provides the space to do so.”

Teachers and administration try to design detention to be focused on fixing behavior instead of punishment, so students understand their mistakes.

“It’s a balance because it’s a punitive consequence, which is serving the hour, but … they’re [also] doing a restorative component,” said assistant principal David Moore. “They have a reflection sheet … [to] explain what they did, what they were thinking when they did it and how they would like to see a change moving forward.”

Some think detention is fair in certain circumstances.

“I believe detention for 10 tardies … is fair,” said senior Daniel Liu. “However, there is a policy where every tardy after that will grant you detention. I believe that’s unfair.”

Oftentimes, students’ punctuality is not in their own control for an array of reasons. For example, traffic in the morning before first period is a particularly painful problem for many students.

“A lot of the tardiness has to do with the parking here in general,” said senior Kamaile Zimmerman. “A lot of people I know who do drive end up being late because they can’t get into the lot in time.”

Another common reason for chronic tardiness is having other responsibilities before school. This reason is also out of a student’s control, making some consider detention to be unfair.

“Some students said, ‘I have to take my little brother to school [because] my parents [are] working,’” said Spanish teacher Ana Maria Ramos. “Because they’re the older brother or sister, they need to help out their families. So … they didn’t have a choice.”

This unfairness leads some students to want changes in the detention system.

“It takes up your time [and] they’re not really … helping”

“It’s not really effective at all,” Manukainiu said. “It takes up your time [and] they’re not really … helping you on what to do. They’re just asking you what you think you could do better.”

The administration works with students hoping to achieve better behavior and attendance.

“Usually, if a student has multiple detentions for tardies, we’re doing a lot of interventions,” Moore said. “We’re contacting families. We’re working with counselors. We’re looking at the schedule of the students to see if that’s an issue. We can work with SamTrans and get bus passes. We can do a lot of interventions to make sure that [there is not] a chronic detention consequence for tardies.”

The system of detention is met with mixed responses from students. The administration is working to make detention an instrument for improvement in order to make Aragon a better place for everyone.