Allyson Chan

Ruhi Mudoi

Written by: Meilin Rife and Grace Tao

On March 3, Principal Valerie Arbizu issued an email denouncing stickers from a white supremacy hate group found in the student parking lot. White supremacy stickers were previously found on Hillsdale and Burlingame campuses as well. Security camera footage revealed the stickers were placed by an individual with a covered face on March 1 after school ended. Students noticed the white supremacy stickers, but did not report them until they were found and removed by staff on March 3.

This follows another incident on Feb. 2 in which hateful graffiti was seen in the boys’ restrooms and on the baseball field fence. Similarly, in September, the N-word was written on a wall in one of the boys’ restrooms.

These incidents are cases of hate speech, which is any form of expression that is discriminatory or aggressive to a group of people on the basis of race, religion, sexual identity, gender identity, ethnicity, disability or nationality.

For many students, witnessing hate speech is common. Junior Kent Ha recalls an incident last year after school.

“There were a bunch of kids drawing [backward] swastikas on the trees [by the bus stop],” Ha said. “There were a lot of people there but nobody else really cared or didn’t notice … [I] hear [hate speech] when I am walking through the halls … every five minutes or so.”

“[I] hear [hate speech] when I am walking through the halls … every five minutes or so”

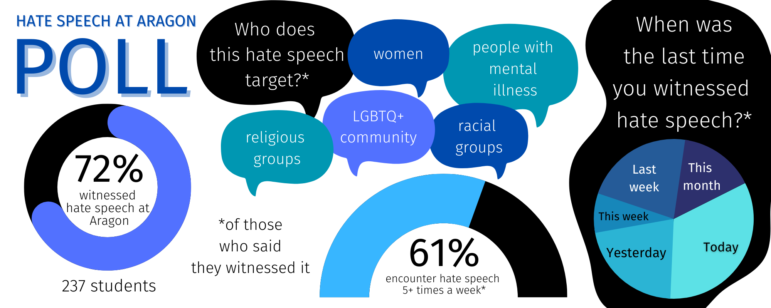

Seventy-two percent of students who took a poll reported that they had seen or heard hate speech at Aragon, and thirty-four percent reported noticing five or more incidents per week.

Freshman Sylvia Demeule* has observed a different variety of hate speech on campus.

“I’ve heard a lot of hate speech [directed toward] women,” Demeule said. “I’ll be walking in the hallway [and I’ll hear] these guys talking about [women’s] bodies. It’s disheartening.”

Some teachers, however, do not typically encounter hate speech in their classrooms.

“In the 33 years I’ve been teaching, I [am hearing] less of it,” said English teacher Patty Riek. “I think that’s for two reasons. One, we are all more aware of how dehumanizing it is. [Two], some of that language has just gone underground. There is an awareness that [hate speech] is harmful, but it continues in a different context. In some ways, that’s even worse.”

Meanwhile, there are also students who rarely encounter hate speech on campus.

“[Aragon] is a [big] school, so there isn’t much policing for the [students],” said freshman Elizabeth Magness. “I haven’t seen a huge amount of hate speech.”

Junior Marissa Rivera offered a possible explanation to why hate speech is sometimes used in conversation.

“A lot of people say the N word, the F word [or] slurs towards the LGBT community to their friends in a joking manner,” Rivera said. “They’re bad words, but [some people] don’t use them [with a bad intent].”

Teachers, who have been at Aragon longer than students, have noticed patterns in the frequency of hate speech cases.

“I’ve noticed that, since being at Aragon, hate speech, while it has never gone away, comes in waves,” said ethnic studies teacher Courtney Caldwell. “[For example], the [Black Student Union] ran a campaign a few years ago … to eliminate the N-word … and it worked. And now [hate speech] is back again.”

While clubs that support marginalized groups like the BSU and Gender and Sexuality Awareness club have done large-scale campaigns in the past, BSU vice president Dariush Norton argued that these clubs should not be held responsible to regulate hate speech.

“It shouldn’t be on the 30 of us to [speak out to] the whole school”

“It shouldn’t be on the 30 of us to [speak out to] the whole school,” Norton said. “That should be in the hands of the administration [or] the leadership program. [It should be] in the hands of a larger body. We would be there to support that, but it [shouldn’t] have to come from us.”

Senior Teagan Robertson commented on the role of the pandemic in spurring hate speech incidents.

“I definitely think that [hate speech usage] got worse after quarantine,” Robertson said. “Quarantine overexposed students to … so much time online, [which negatively] impacted the amount of hate speech and microaggressions on campus.”

Aragon Student Body President Benjamin Wen notes similar observations.

“Many leadership students have expressed that campus culture feels very different,” Wen said. “Seniors who were here before the pandemic say that the school culture feels a lot less respectful.”

Leadership began seriously discussing hate speech after the recent incident, though concrete action has not yet been taken.

“The difficulty with [reforming] school culture is that it’s not quantitative,” Wen said. “It’s not [an issue] where we can pinpoint the [reason behind] the lack of respect. It’s really hard to change school culture, the way people see their school community and how people interact with each other.”

Senior Joseph Neamati expresses why minimizing hate speech is especially important in high school.

“Hate speech is something that can be very impactful [on] a lot of students’ well-being and especially their mental health,” Neamati said. “Being surrounded in an environment where that’s not taken seriously can be frightening for a lot of people. Not only that, if school is the place where we’re supposed to learn how to behave in the future, [addressing hate speech] really needs to be [prioritized] to remind people that this is not any way to conduct yourself and interact with others.”

However, a few students express skepticism as to whether hate speech behavior can ever be eradicated.

“It would be pretty difficult [to get students to stop saying hate speech] because it’s already reinforced in the way some people speak,” said junior Kay Hiura.

“And I know a lot of people don’t poke into business that isn’t theirs [to avoid] getting themselves involved.”

Junior Isaac Sanchez offers similar sentiments.

“There’s only so much they can do. I guess it’s pretty disappointing, because you expect the administration to do something, but you don’t know what they can do”

“Honestly … I can see [a] point where they can’t do anything about it,” Sanchez said. “There’s only so much they can do. I guess it’s pretty disappointing, because you expect the administration to do something, but you don’t know what they can do.”

Currently, Aragon has some preventative measures in place, including the grade-level assemblies at the beginning of each school year.

“People will say we need to have an assembly on [hate speech],” Arbizu said. “Yes, but only if we can follow through consistently. [In addition], I know it doesn’t feel like a lot, but we do have ethnic studies, where teachers are talking a lot about differences, inclusion and what it looks like to understand other people. I think another kind of minor item that we’re using is [the] Aragon CARES [program]. I think you can talk about the expectations in a positive way, so you’re not constantly having to say ‘don’t’ [or] ‘no.’”

Punitive consequences are one tactic used to combat hate speech, as expressed by Arbizu.

“We try to give students an opportunity to understand that it is hateful, and not acceptable,” Arbizu said. “[However] it depends on [the] context. If somebody is using hate speech in a hateful manner, they don’t get to stay on campus, they will have a suspension because it’s absolutely unacceptable. We [also] make sure that the person who was victimized [has] support … [and] that they feel safe and heard.

We will offer and try to get kids talking to each other, if both parties agree.”

Administration determines the punishment for hate speech on a case by case basis, after considering intent and impact.

“[For example,] if it’s a couple of students talking to each other, and using language that is classified as hate, but they’re friends, teasing each other [or] it’s part of the vernacular, we deal with that differently,” Arbizu said. “It depends on the severity, so it’s pretty nuanced.”

Assistant Principal Andrew Hartig observes that hate speech is somewhat normalized and widespread.

“Some people feel that it is socially acceptable [to use hateful language],” Hartig said. “Unfortunately within our culture, we hear it in music [and] on television. It’s just part of the air we breathe as a society.”

Hartig expands on the investigation process that ensues after an incident.

“We want to find who the perpetrator was,” Hartig said. “In the case of graffiti, we have a collection of campus [incidents kept] in a database, [and] sometimes we can match that to a person. [We] also use our surveillance camera system.”

Regarding the white supremacy sticker incident, Arbizu emphasizes the importance of reporting these incidents when students notice something.

“It was just unfortunate that nobody said anything,” Arbizu said. “If you have a lot of kids, they all assume that someone else is going to say something and 99% of the time nobody does.”

While the administration does make preventative efforts, Hartig indicates a desire for change.

“I do think [we should have] a more proactive approach [toward educating] the school about [hate speech],” Hartig said.

Dean Donna Krause also notes a potential reason for recent hate speech incidents.

“I think kids are [still] hurting from the pandemic,” Krause said. “Kids don’t know how to cope [with] the [effects of the] pandemic. For the most part, I see that kids are very angry.”

Furthermore, Krause encourages restorative efforts.

“There will be many times when I will do restorative mediation, and they walk out with agreements about what they’re not going to say anymore,” Krause said. “‘Alternative to Suspension,’ [is] a therapeutic class [with] kids from different schools [where] kids hear from others what happened, why they are there, what they [did] wrong, [and] what kind of trouble they got into.”

Arbizu elaborates on the current policy for hate speech incidents as they occur.

“We handle it] as it pops up, like Whac-a-Mole”

“[We handle it] as it pops up, like Whac-a-Mole,” Arbizu said. “Now what? Who’s doing this? In regard to Aragon’s history with hate speech, it hasn’t really gotten to the point where we felt a need to greatly change policy at all toward it.”

*An earlier version of this article misspelled Sylvia Demeule’s name. It has now been corrected.