Zelda Reif

Written by: Grace Tao and Leah Hawkins

Process

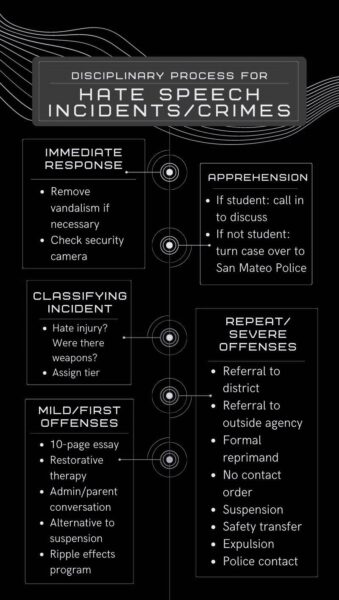

When a hate speech incident is reported, Aragon’s administration goes through a series of steps to evaluate the severity and intent of the incident to determine whether or not the offender should be suspended, and to decide upon the education and conversations that will take place following the suspension.

“That restorative conversation where somebody can articulate how that language or image or incident made them feel and how they were hurt is the most effective [method],” said Principal Valerie Arbizu. “It’s the most difficult to [organize] … but [it] humanizes the situation; usually, there’s been some dehumanization that needs to be reversed. And [we] just have a conversation about it — calling people out and saying ‘this is not okay.’”

“For the most part, [a conversation] stops the behavior and if it doesn’t, they don’t get to continue being an Aragon student”

For repeat offenders, consequences go a step further. Dean Donna Krause acknowledges the benefit of written reflection for mild offenses.

“If it’s a second or third time I will make them write me a paper on what it means to [use hate speech],” Krause said. “I want to find out what your motive is. I want to find out why you continue to do it. I want to find out what’s behind it, what’s underneath it and ways you’re going to prevent it from happening again.”

When even these actions fail or there is a more severe violation, there are harsher consequences such as expulsion or suspension.

“For the most part, [a conversation] stops the behavior and if it doesn’t, they don’t get to continue being an Aragon student,” Arbizu said. “If it’s such a safety concern … then the behavior doesn’t get to be here.”

Education and rehabilitation need to be meaningful to be effective.

“In some cases [students] don’t know whether it was what they said or did that caused such a scene,” Arbizu said. “[For example], our alternative to suspension program … is working with a wellness counselor and reviewing, what was the behavior that you exhibited, and how did it cause harm? Who did it harm? How do you make sure that you don’t do that again?”

Context

Staff members who have worked at different schools throughout Silicon Valley offer comparisons with other campuses, noting differences in demographics and histories as factors which contribute to hate speech prevalence.

“[At Aragon] I’m not seeing the same level of racialized tensions as I saw at Burlingame. I don’t see the same level of animosity”

Modern World History teacher Scott BonDurant used to teach at Mission High School in San Francisco with an over 90% minority population before coming to teach at Aragon starting this school year. According to BonDurant, Mission has noticeably less hate speech.

“At Mission, if you said something racist and xenophobic about immigrants, you just wouldn’t do that because 40% of the school are immigrants,” BonDurant said. “Even students born in the U.S., their parents are probably immigrants. Worldviews are so different because of the experiences. [Hate speech] was self-regulating at Mission and [that came] from a place of lived experience.”

For Arbizu, her experiences as an assistant principal at Burlingame High School provide her with a different perspective about inclusivity at Aragon.

“The [Aragon and Burlingame] communities have very different histories,” Arbizu said. “We have some neighborhoods [around Burlingame] that have a history of racial segregation that lingers a bit. At Burlingame, the big [hate speech incident] we got hit with [involved] 13 different acts of vandalism in one night. It was awful; It was homophobic, it was anti-black, anti-Asian, anti-you name it. [At Aragon] I’m not seeing the same level of racialized tensions as I saw at Burlingame. I don’t see the same level of animosity.”

Moving Forward

Some teachers have indirectly addressed inclusivity in their classrooms.

“I’m trying really hard to think about how I would use terms that are not gendered,” said AP Biology and Biotech teacher Katherine Ward. “[I’m thinking], ‘how would I teach a unit [that] more appropriately [describes] the biology [without] overlaying [it with] social constructs?’”

Some Aragon departments have worked together to create lesson plans that, while not directly addressing hate speech, focus on promoting inclusivity and conversational mindfulness.

“[My class] is going to talk about this idea of saying enslaved people versus slaves [and saying] illegal aliens versus people who are undocumented,” BonDurant said. “Issues of class are something we have a ways to go [on] and we’re going to do a whole lesson exploring root causes of homelessness and misconceptions around it.”

The CP Modern World History teachers have condensed this lesson into a worksheet titled “Humanity First – People Experiencing Homelessness,” which allows sophomores to explore the comparative connotations of terms such as “people experiencing homelessness” versus “homeless people” to promote respect.

“We [shouldn’t] need to wait for something to be in the newspapers for it to be something we need to consistently come back to”

The worksheet states, “The words we use have power. Language can positively or negatively affect how we think about something, including people and their identities. When talking about people, we always want to be humane.”

The worksheet also acknowledges the potential political debate involving the use or avoidance of such terms: “Nobody at AHS will ever tell you who you should or should not vote for, which political party you should or should not support or try to tell you that your political opinions are wrong. But no matter what your political beliefs and party affiliations are, remember to always [put] humanity first.”

AP U.S. History teacher William Colglazier points out the necessity of constant attention to hate speech in the community to truly address the issue.

“I remember when the #MeToo movement was really big, we had the whole school day focusing on important issues around women’s rights [with] guest speakers,” Colglazier said. “[But] we [shouldn’t] need to wait for something to be in the newspapers for it to be something we need to consistently come back to.”

Culture

Senior Erik Dodge conveys his experiences in dealing with the nonchalant nature of hateful language.

“With the LGBTQ+ community, [it’s] very normalized [for people] to use words that are negative,” said senior Erik Dodge. “As someone from the community, when they say [slurs], it’s hurtful. [But] we don’t say it’s hurtful because so many people use it. How can I stand up to these people and tell them that they’re making me feel uncomfortable? Like, is my sexuality invalidated when [people] say [slurs]?”

Despite the known impact of hate speech, such language is typically exchanged offhandedly among students, making its harm more difficult to control. English and AVID teacher Victoria Daniel offers her perspective on the indifference around hate speech.

“I wish we had more strategies for helping [students] out, how do I build the community I want?”

“It’s [part] of teen culture,” Daniel said. “We’re fighting against a world, both digital and in real life, where students see and hear language that conveys [hate] all the time. It almost [normalizes] it. The challenge is that we are fighting against forces that can be very deeply ingrained. So teaching morality is a challenge in itself.”

Junior Trish Clemente Perez expands on this idea behind hate speech at Aragon.

“[Students use hate speech] because they just want to act cool in some way,” Clemente Perez said. “Especially when they’re in a big friend group they tend to say [hateful] words. [But] when most people are by themselves they don’t say anything. It’s the [peer] pressure.”

For teachers, casual use of offensive language can be challenging to combat.

“If I do hear it in the hallway, most of the time I just keep it short and sweet,” Daniel said. “I’m not going to launch into any [lecture] because I know I’m not going to be listened to. [I’ll just say], ‘We are not talking like that. That language is not necessary.’”

Ward addresses the potential challenges that teachers face when trying to ensure that lessons of inclusivity follow students past high school.

“I wish we had more strategies for helping [students] out, how do I build the community I want?” Ward said. “How do I build a community that values language that doesn’t alienate or make somebody feel uncomfortable? Because [they’re] going to need to know how to do that in the next spaces that [they] occupy.”

Continuous education can be neglected when it comes to solidifying an understanding of hate speech and its effects.

“We acted out scenarios of hate speech, but we never fully went through how we should talk about it, what is the language we should use and what are the conversations we should have”

“Every year there’s a new class of freshmen, and you have to restart the teaching of [hate speech],” Colglazier said. “Even though you’ve seen some posters around the school, [we] did that campaign, but then you can’t just say, you got it, you did it, check it off, right? We have to redo it. Sometimes we forget [that] the new students need re-education.”

Daniel feels that there is something lacking in the current education teachers receive on combating hate speech in the classroom.

“[In one professional development] we acted out scenarios of hate speech, but we never fully went through how we should talk about it, what is the language we should use and what are the conversations we should have,” Daniel said. “We stopped too short. I’m all about giving teachers the language and the practice talking about [hate speech] because [the] context in which it was said matters.”

Krause offers an administrative perspective on staff professional development meetings and the anti-hate speech efforts embedded within them.

“We’ve talked a lot about [hate speech] in our professional development meetings,” Krause said. “It’s never far from the forefront.”

Prevention

Although no current preventative measures were mentioned, administrators mentioned various plans to prevent hate speech in the future, as incidents continue to occur.

Traditionally, Aragon addresses hate speech at the beginning of the year assembly, but administration has found this method inadequate in reducing hate speech on campus.

“Whatever we do moving forward to prevent [hateful] language needs to be more than just an assembly,” Arbizu said. “Assemblies are just a one off [thing], but a large part of what we’re seeing is students reporting they hear things all the time, but [individual cases don’t] get reported. It’s like … ’I don’t want to have to call people out all the time.’”

“Whatever we do moving forward to prevent [hateful] language needs to be more than just an assembly”

Students support the prospect of additional methods to deal with hate speech.

“[Administration] does send an email [after hate speech incidents], but they [use] more of a reactive approach, not [a preventative one],” said sophomore Keira McLintock. “They’re just trying to save face when they send these emails, and say [to parents], ‘oh, yeah, your kids might have told you, but we’re definitely doing something about this, don’t worry about it.’”

Next year, Aragon’s administration and leadership plans to prevent hate speech by partnering with a currently undecided outside organization that aims to educate students. The programs under consideration include the Anti Defamation League’s No Place for Hate initiative and the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Learning for Justice initiative. These programs would focus on continuous, year-round education and conversations with students around hate speech.

Read part one of the Fighting Words series here.