Eva Ludwig

Written by: Leah Hawkins & Grace Tao

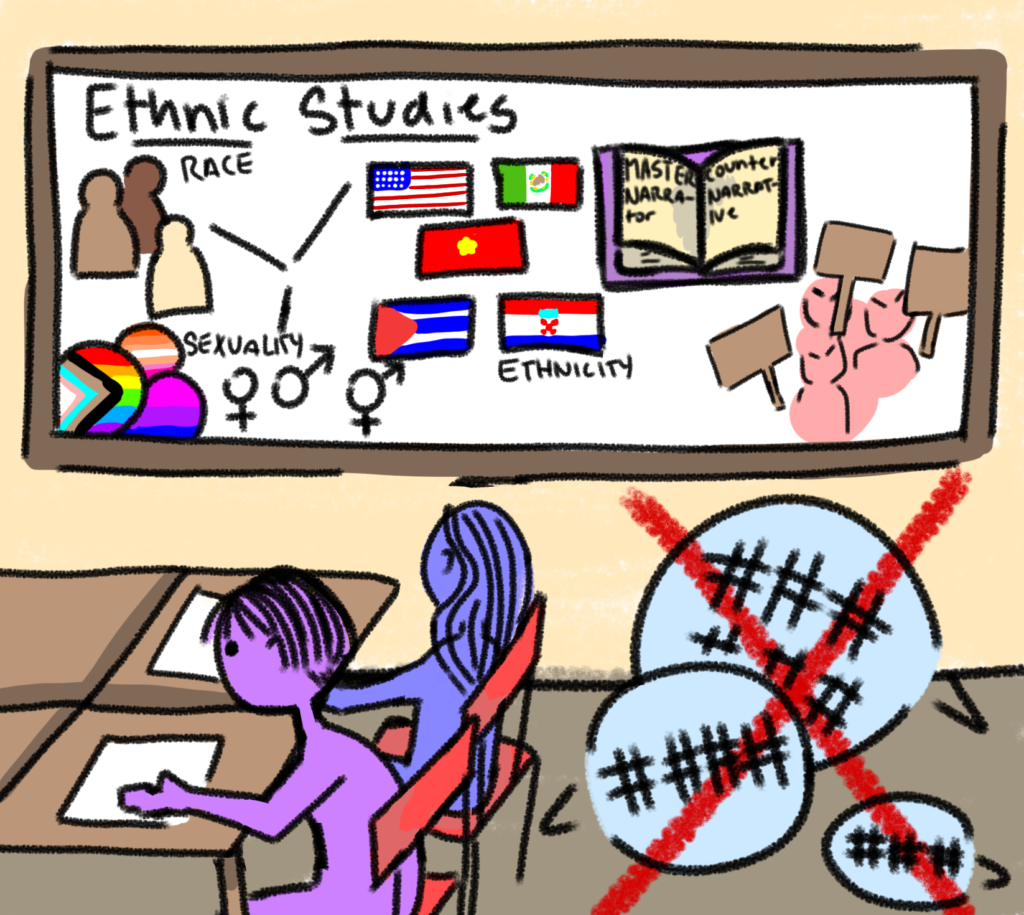

In late 2021, California was the first state to write a law requiring high school students to take Ethnic Studies before graduating. This graduation requirement will take full effect in the 2025-26 school year. Taken in the freshman year, Ethnic Studies addresses marginalization in race, ethnicity, sexuality, gender and culture to promote inclusivity among students.

Starting in the 2020-21 school year, Ethnic Studies was mandated as a necessary course for graduation at Aragon. This requirement was implemented a year before the state mandate addressing Ethnic Studies in schools was signed.

Recently, several San Mateo Union High School District open board meetings were dedicated to the discussion of issues covered in the Ethnic Studies curriculum. A study session on March 15 covered course aims, content and student-reported impact.

At Aragon, the course contains three units: Identity, Race and Ethnicity and Gender and Sexuality. These units are taught through inquiry-based lessons, including but not limited to hands-on projects, music analysis and documentaries.

“One of the most impactful lessons we do [is] around Black Lives Matter,” said Ethnic Studies, AVID and leadership teacher Courtney Caldwell. “That lesson looks at the stories of eight slain individuals who lost their lives at the hands of either the police or vigilante justice. We look at what actually happened and [whether] justice was achieved.”

“Students learn what to say and what not to say … They’re more mindful about it”

Caldwell emphasizes the critical thinking skills students build throughout the course.

“[Ethnic Studies is about] the history but also the thought process,” Caldwell said. “How am I becoming an informed citizen? How do I share my voice in a way that’s constructive?”

Though discussion-based, the course content has been controversial. On May 7, principal Valerie Arbizu issued a response to “recent inquiries about [Aragon’s] Ethnic Studies and U.S. History curriculum, and a handful of difficult and troubling transphobic email communications [she has] received from parents and other community members.”

In her response, Arbizu emphasizes the lessons of inclusivity embedded in Ethnic Studies.

“It is important that every student feel seen, heard, understood, and included at AHS, regardless of their race, color, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or disability,” Arbizu wrote in the email.

Caldwell also acknowledges the potential political concerns about the curriculum.

“We’re not here to force opinions on anyone,” Caldwell said. “We have to provide enough context for lessons. It’s [multiple narratives] coming together to complete the full story.”

Ethnic Studies was in part implemented to reduce hate speech by encouraging community and open conversation on potentially sensitive subjects.

“Ninth graders come in with this idea that talking about race is racist,” said San Mateo Ethnic Studies teacher Edward Montelongo, who helped write the course for the district. “A big part of [Ethnic Studies is] socializing young people and training [them] how to talk about race. I noticed that by the end of the class, a lot of young people are just much more comfortable talking openly about the idea of race and racism and how it happens.”

With these aims, some students noticed how the class encourages thoughtfulness in everyday interactions.

“[Students] learn what to say and what not to say,” said freshman Maria Gevorgyan. “They’re more mindful about it. You know [about] the races around you and what they have gone through. Instead of saying jokes that might be offensive.”

Others recognize how the course has gone against media depictions of certain topics, shedding a new light on world issues.

“It can’t just be our sole responsibility … It has to go beyond our classrooms as well”

“I think that it’s an important curriculum that should be taught in school because it teaches students about racism, sexism and [other] problems in the modern world that need to be discussed, because oftentimes, the media doesn’t give a good representation of these [movements] like feminism, for example,” said freshman Midori Saito.

However, some students believe the course is ineffective in limiting or preventing hate speech in the long term.

“You learn where [some of] these words come from, [but] you don’t learn where everything comes from,” said freshman Nyla Garrick. “It doesn’t have a lasting effect … because you hear it once and it’s in one ear [and] out the other. [Ethnic Studies] isn’t decreasing racism, because people are always going to say stereotypical jokes or microaggressions.”

For other students, lessons on personal identity stand out the most.

“I think it educates people who would otherwise get frustrated or confused about things [such as] pronouns or gender,” said freshman Samantha Stanley. “It educates people so they don’t have to be … frustrated and upset.”

One student describes a particularly enlightening lesson the class provided.

“We learned about the four I’s of oppression,” said sophomore Melody Chen. “That was interesting to learn because I never knew about that. And it was like, ‘Oh, that makes sense now because I see it [around me]. I just didn’t have a name for it.’”

“[Ethnic Studies] isn’t decreasing racism, because people are always going to say stereotypical jokes or microaggressions”

Ethnic Studies teacher Steve Henderson touches on the importance of connecting with classmates from different backgrounds.

“[Ethnic Studies is] an opportunity to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes,” Henderson said. “[It] gives people a chance to reflect on their own lived experiences, and also appreciate others … [It] gives everyone a chance to identify within the American story.”

Likewise, Caldwell hopes that students leave the class with a more accepting view of the world.

“I’m hopeful that, while Ethnic Studies isn’t necessarily for everyone, whether they’re not interested or they disagree, … that everyone comes out with more of an open mind,” Caldwell said. “Regardless of the content being taught, [I hope] it makes people stop and think a bit more before they speak or act.”

This goal is not unique to Aragon. Burlingame Ethnic Studies and Government teacher Alexandra Gray comments on how the course has altered student culture on Burlingame High School’s campus.

“I have heard very positive accounts of people calling one another out [when] students hear something, either a slur or some sort of microaggression,” Gray said. “Students who have taken Ethnic Studies feel more empowered, they have more agency and they’re able to call out their fellow students in the moment. Whereas maybe if they hadn’t had that practice, and that knowledge from Ethnic Studies, they wouldn’t have done so.”

Gray explained that in the wake of Burlingame’s recent hate speech incident — one perpetuated by a non-student who posted stickers advertising a white supremacist website — she felt upset at the notion that racist organizations sought to recruit high school-age students. However, in addition to teaching Ethnic Studies, she felt as if Burlingame’s administration took adequate measures to combat hate speech.

“We have a very new administrative team here at BHS,” Gray said. “And I think they’ve been doing a phenomenal job. There have been [hate speech] incidents … [with] stickers of graffiti [and] … inappropriate words or symbols. Admin really clamps down on monitoring bathroom and hall passes, [and] I believe they installed new cameras to try to catch [perpetrators]. I believe that [incidents haven’t] happened now for a while.”

“Students who have taken Ethnic Studies feel more empowered, they have more agency and they’re able to call out their fellow students in the moment”

Montelongo brings up some of the biggest issues the course faces when working to reduce hate speech on the San Mateo campus.

“How do you get young people to change the way they speak when they don’t see it as a problem [themselves]?” Montelongo said. “That is an area of growth for the program, at least at San Mateo, is providing more opportunities to engage with specific or concrete scenarios that students find applicable in their local environment.”

To combat these challenges, he expresses the importance of knowledge.

“We’ve had some assemblies on … identifying this use of hate speech, but there’s no data collection to speak to the efficacy [of Ethnic Studies],” Montelongo said. “[And] I’d be interested to see some [more] data [because] … awareness is the first step.”

Caldwell notes that Ethnic Studies is just one part of the larger Aragon commitment to preventing hate speech in the community.

“As a team, we have a responsibility to address it in the classroom, and we talk about dehumanizing language and how harmful it can be,” Caldwell said. “But it really stems beyond our classroom. And it should be the commitment across the school to address it. It can’t just be our sole responsibility … A team of three [in] a staff of 80 is just a drop in the bucket. It has to go beyond our classrooms as well.”

However, nationally, states are divided on the issue of Ethnic Studies. In 2012, Arizona banned Ethnic Studies, a law that was overturned in 2017, but is currently at risk of being reinstated. Only nine states — California, Connecticut, Indiana, Nevada, Oregon, Texas, Vermont, Virginia and Washington — have established standards for Ethnic Studies courses in K-12 education. Currently, California is the only state to mandate the class for high school graduation.

Read part two of the Fighting Words series here.