Allyson Chan

Art transports us to different worlds: we laugh, cry and love, as art offers us an escape into universes fundamentally unlike our own.

But too often, we reach for the worlds closest to us. We turn the pages of books listed as ‘best-sellers’ and bop along to the tunes of top-100 hits. We consume the media recommended to us—the media of the masses. In doing so, we rob art of its power to shatter the bubbles we live in. The question then becomes: how do we diversify the media we consume in a purposeful manner that celebrates the merit of a work and avoids the red flag label of ‘tokenism?’

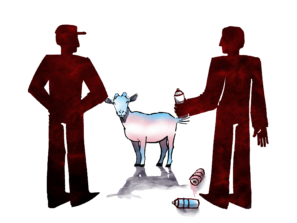

Tokenism is making a superficial effort to highlight underrepresented groups to create a false appearance of equality by choosing a small number of minorities. In practice, tokenism means choosing diverse works to ‘check a box’ because of their diverse nature, not because of their merit.

“Tokenism, in terms of connotation, is super loaded,” said writer and English teacher Genevieve Schwartz. “As a teacher, I never want to feel like I’m choosing a writer simply because they are an African American writer, an Asian American writer or a queer writer. That, to me, is an incredibly shallow philosophy about how we choose what to read.”

Instead, we should redefine how we understand our selection of media.

“It’s not tokenism, it’s broadening our perspectives,” said English and AVID teacher Victoria Daniel. “We have to be aware of how we’ve silenced voices by not considering them.”

Through that lens of curiosity, we can evaluate the media we consume.

Diversity in art comes in two forms: diversity in story-tellers—those who produce media—and diversity in the stories they tell. We should listen to diverse storytellers, whether in terms of literature, music or art, because their experiences navigating the world through their intersectionalities shape their work. Those artists can lead us down paths we wouldn’t travel in our own lives.

“The artist creates the art,” Schwartz said. “The art comes from the artist.”

However, artists shouldn’t be cast aside just because they don’t check the boxes of diversity. While ‘old, white, straight men’ do oversaturate the media, that doesn’t immediately discredit the merit of their work.

“I remember listening to Ocean Vuong, a beautiful Vietnamese poet,” Schwartz said. “He talks about the influences on his work and he cites writers of color, but he also cites dead white male writers too. It’s a little dismissive to just say ‘that’s a dead white male writer’. It throws the baby out with the bathwater.”

“It’s a little dismissive to just say ‘that’s a dead white male writer’. It throws the baby out with the bathwater”

Second, diversity in stories is equally essential. Diverse stories bring important and overlooked issues to light in creative ways. The unique power of art makes us question the very nature of the human experience.

But a single artist cannot speak for an entire population.

“A lot of the black female writers [we teach] write about oppression,” Daniel said. “That’s not their full story. And so it does become tokenism, because they’re so few writers that get to be studied in a classroom that you don’t want that one voice standing for them all.”

Each artist has a story to share—but every artist’s story isn’t the same. Internalizing just one story without appreciating other perspectives reinforces stereotypes and narrows our understanding of different communities. To properly seek diverse voices, we have to hear a multiplicity of voices.

However, consuming diverse media is only half the battle: media publishers offer vanishingly few opportunities to artists from underrepresented backgrounds. Why? Media companies prioritize profits above all else. That profit incentive deters media companies from taking risks, like publishing new artists speaking truth to society’s glaring inequalities. Take publishing houses as an example: according to Words Rated, a literary research organization, 95% of American fiction books published between 1950 and 2018 were written by white authors. And while recent pushes for diversity have made strides towards inclusivity, further reform is needed.

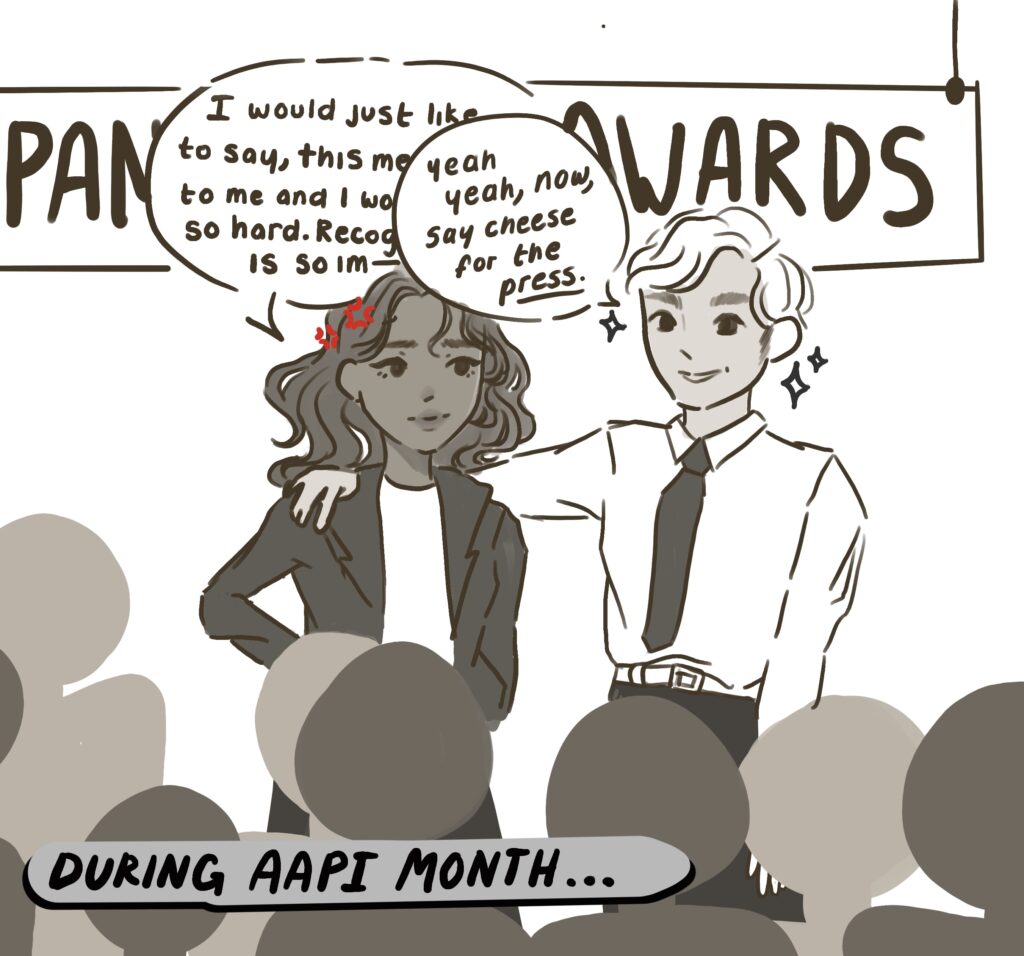

While a handful of diverse authors become popular, the vast majority go unread; even those who succeed are too-often written off as the beneficiaries of affirmative action, rather than the artistic geniuses they truly are. Awards and honors often feel tokenistic, with diverse authors selected merely to “check the box.” Media companies applaud diversity only as a smokescreen to avoid accountability. In 2020, for example, only 22 of the 220 books on the New York Times’ fiction bestseller list were written by authors of color. The fact that these numbers spike around social events centered around minorities—like the Black Lives Matter movement—raises further suspicions of performativity.

For students, this often manifests in the works studied in classes. Specialized curriculums, like AP, are specifically restrictive.

“[The AP Literature curriculum] asks us to teach classic works from roughly the 1600s on,” Schwartz said.

And because the works in those eras were predominantly written by white men, it becomes significantly more difficult to promote diverse voices. Teachers navigate the issue by aspiring to what Schwartz calls an “expansive exposure”.

“That exposure shouldn’t be limited to one certain kind of writer,” Schwartz said. “Whether it is from the perspective of a female writer or a queer writer or writer of color, by the time a student leaves a four year program here at Aragon, [we want to ensure] that they’ve had exposure to multiple voices that reflect the community in which we live or the world in which we live.”

“[B]y the time a student leaves a four year program here at Aragon, [we want to ensure] that they’ve had exposure to multiple voices that reflect the community in which we live or the world in which we live”

At the end of the day, we should consume diverse media because we want to—because we want to broaden our horizons and understand those different from ourselves.

“Curiosity is key to guiding our consumption of what we call diverse [works],” Schwartz said. “It needs to stem from a genuine curiosity about how people experience the world, and how [you] experience the world might be very different from how someone else does because of gender identity or sexual identity or race or class.”