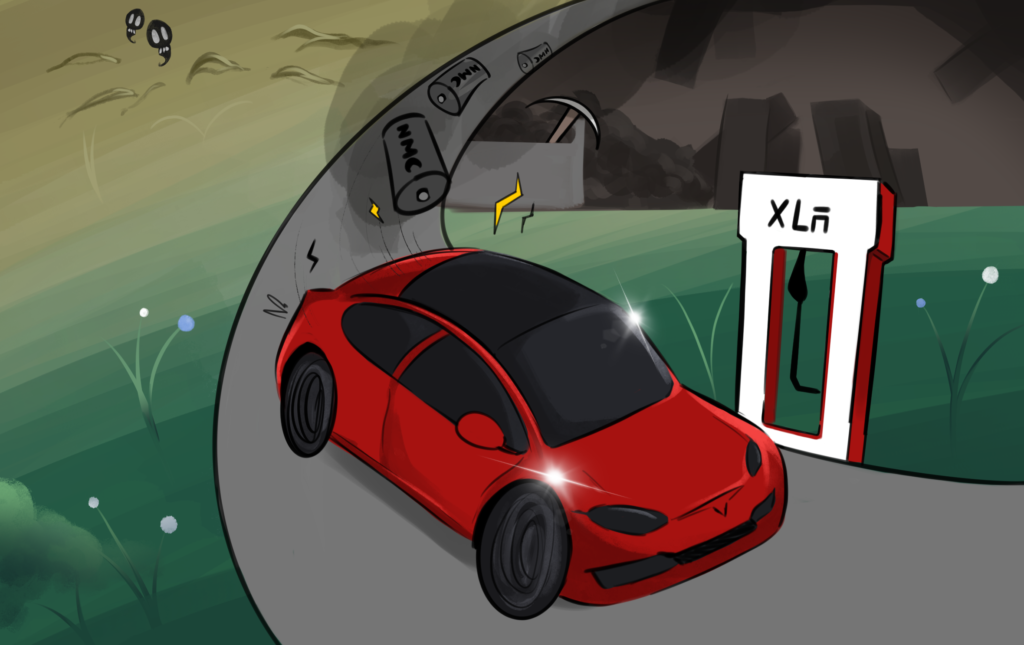

Underneath the shiny, futuristic exterior of a Tesla lies the queasy, dirty origin of the materials inside. California’s shift to 100% zero-emission vehicle sales by 2035 aligns with the projection that by 2030, electric vehicles will make up 40% of global vehicle sales. In a country where the transportation sector tops all others for the highest greenhouse gas emissions, this switch from combustion engines to battery-powered is a step in the right direction. But beyond carbon emissions, there are still many hidden environmental impacts of EVs that need to be considered.

Many problems stem from the materials in car batteries, specifically, lithium. Lithium-ion batteries are popular in EVs because of their high energy density, allowing cars to run for longer periods of time.

Conventional lithium mining operations pump out gallons of subterranean brine onto desert flats. Once evaporated, the previously unusable brine leaves behind lithium carbonate, which is then processed into lithium.

Much of this mining takes place in the aptly named Lithium Triangle, the salt flats between Bolivia, Chile and Argentina. According to the Chilean government, the fresh groundwater used in mining and processing lithium in this area has resulted in a 25-inch drop in underground aquifers.

The Atacameño indigenous population living in these areas have a spiritual connection to the land, and have not consented to the land being abused by energy companies — not to mention the limited water for maintaining crops and livestock. These corporations are largely owned by international investors, who often cite the potential of new jobs for locals as a way of downplaying risks to the environment. Cobalt, another problematic element, is included in car batteries because of its high heat capacity properties, protecting batteries from exploding. When it was discovered in 2014 that Kolwezi, Democratic Republic of the Congo had rich stores of cobalt, many saw it as a way out of poverty. It was like the California Gold Rush as the remote town’s population grew to half a million. With treasures right under their feet, everybody wanted in. Today, the DRC produces 70% of the world’s cobalt.

There are two types of cobalt mining, artisanal and large-scale mining. Some artisanal miners (one-fourth of cobalt mining in the Congo) opt to dig holes themselves into their own backyard. Some of these can reach deeper than 100 feet, many without any structural support, resulting in collapses. The most deadly collapse in 2020 took more than 50 lives. The problem here is not that there are miners working to make a living, it is that, without proper adherence to DRC’s mining codes, the amateur diggers have to put their lives at risk in order to do so.

Even large-scale mining, which uses open pits, has drawbacks to the local community. Cobalt is toxic to breathe and touch, so when the smallest gust of wind kicks up the dry dust from these expansive pits, it can create a poisonous atmosphere. The local rivers that flow into the wider Congo River are so contaminated with acid that it has taken a blank greenish tint, obscuring the lack of life below. From dust-filled air to contaminated water, the people living in the region around Kolwezi, already living on $2 a day, suffer from a disproportionate increase in birth defects and withered crops.

Is it reasonable that in a country so rich in natural resources, the people of Kolwezi have such a poor quality of life thanks to the pillaging of foreign companies?

The answer to our climate crisis is limiting consumption, of both fossil fuels and precious resources, not bandaging up the issue with electric vehicles, which is still indirectly producing carbon dioxide by proxy of non-renewable energy plants. Is the shiny new Tesla or iPhone model really necessary to buy? Can the California government improve the public transit system instead of installing 1.2 million charging stations?

There is a difference between innovation and the insatiable need for resources that are creating these exploitative relationships between EV manufacturers and the locals in the areas where these resources are mined. The rise in electric vehicles still has negative environmental impacts, but they have been forced onto unseen communities. Modifying activist Martin Luther King Jr.’s words, environmental injustice anywhere is environmental justice nowhere.