“I didn’t have many other Polynesians in my area growing up, so I wasn’t as motivated to push myself,” said sophomore and Poly Club president Shana Vick. “I didn’t have that sense of community, [or] feel as supported.”

Comprising a mere 45 out of 1,757 Aragon students, Pacific Islanders are one of the smallest ethnic groups, which gives rise to potential feelings of alienation among members and often leads to a lack of academic interest.

This manifests itself in state test scores; while Aragon students most commonly fall in the above standards category for both English and Math for the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress Test, the majority of Pacific Islanders are at/near standards for English and below standards for Math.

However, given their small population, changes in percentages seem even more dramatic since one person accounts for around 2.2% of the entire group.

“The fact that [it hasn’t been] fixed implies that underrepresentation is a complex issue,” said chemistry and AVID teacher Max Von Euw. “We’re in one of the best funded school districts in the Bay Area, but the statistics clearly [show] there are groups of students who are not being served. When I look at my D and F rates for my chemistry classes and I see particular groups of students that are appearing, it’s like, ‘what can I do and how do I work with that particular group or those particular students?’ It weighs on a lot of our teachers.”

The reasons for the achievement gap itself are widely debated, from generational oppression to socio-economic challenges. Still, underrepresentation can cause tangible harm.

“In general, feeling underrepresented can create feelings of isolation and affect self esteem,” said wellness counselor Jillian Ma. “It doesn’t necessarily happen to every person, but it can affect some people’s emotional health. Not having a sense of belonging can feel very isolating. [Underrepresentation] is a real issue — but you’re not alone in your experience.”

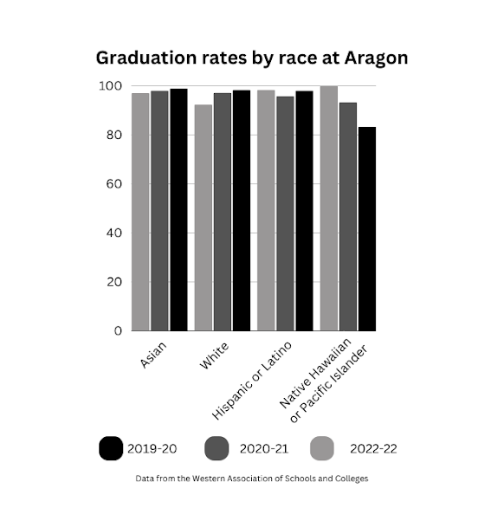

Pacific Islander enrollment rates have dropped to half of what they were in 2017 and graduation rates have decreased from 100% to 83.3%. In 2022, only one graduate met A-G requirements, a drastic drop from 11 the year prior. There have also been multiple fluctuations in absentee rates since 2018-19, ranging from 23.9% to 10.6% to 41.3%.

As the Pacific Islander population continues to drop, the challenge of finding a sense of belonging only becomes more difficult.

“Community is very big in Polynesian culture,” Vick said. “As more and more of our brothers and sisters leave and graduate, it can impact us as a student body. We’ll think, ‘well, my brothers and sisters have already left so what’s the point in me even trying, who’s here to push me to continue to try and do better?’”

However, some still are motivated by family ties.

“Polynesians at Aragon right now are more focused on graduating not only for themselves, but for their parents and families,” said freshman Lupeuluvia Manuma. “And it’s what our parents really worked for, so we can give back to them.”

Some minorities will fail to find their culture taught both at home and in school, which can lead to indifference towards their studies.

“All of our parents are hardworking and most were immigrants still trying to achieve the American dream,” said sophomore and Poly Club secretary Iris Hoeft. “Since they’re always busy with work, we never get to actually learn about our culture [at home] and when we come to school, we’re not really taught here either. When I took ethnic studies last year, we barely learned about my culture, and in some cultural studies classes in eighth grade, the closest we would ever get would be Native Hawaiian culture. So we’d become uninterested and I think that [could] be evidence for some dropouts.”

This can also impact student’s engagement with their teachers.

“If you’re not seeing your [ethnicity] represented in school, you [can] get the sense that this educational world might not be for you or you don’t belong to it,” Von Euw said. “That could have an adverse effect on motivation to do well or on knowing how to do well. It’s hard to explain yourself [and] be open with educators, who you’re supposed to look up to, if you don’t feel like they understand where you are coming from.”

In Panorama survey data, students reported that teachers only encourage them to learn about people from different races, ethnicities, or cultures around 50% of the time. Without knowledge about different groups, people can end up stereotyping others.

“One of the main reasons we decided to reinstate Poly Club is because of the false narrative that we have as Polys in the student body,” Vick said. “We feel like we’re misrepresented as [being] loud and boisterous [but] we’re loud and boisterous because we’re very proud and open about our culture. [Others see] what we find in our culture as a strength and take it as a negative so that can be very harmful to us as students here. And our culture can seem embarrassing or too much when, in reality, it’s everything it needs to be.”

The harms of stereotypes also permeate into academics.

“Most people know us for sports and it feels as though we’re not up to [academic] standards, because we’re more viewed for athleticism than knowledge,” Vick said. “So it’s like, ‘well, if people aren’t viewing us as knowledgeable then why should I try and prove to them that I am?’”

Poly Club aims to counter false narratives and deepen understanding of Polynesian culture, and officers highly encourage attending meetings on Wednesday in Room 258.

“As the Polynesian community, we tend to stick together,” Vick said. “It can be intimidating because we’re so tightly knit, and it can seem that we aren’t open to other people. But that’s not the case – we’re very welcoming to other cultures. I wish people were more inclined to come to Poly Club and learn about us and share their culture. You don’t have to join, but maybe just come in, check out what we do. You’ll see that it’s very open and welcoming and you’ll be able to feel the sense of family that we have.”