When she was 16, senior *Inez visited a foreign country on vacation. There, she found herself at a party which, while fun at first, quickly turned sour.

“There was this one guy who was around 23 years old,” Inez said. “He was talking to me and I didn’t want to be rude, so we kept talking. All of a sudden, he … came closer and tried to kiss me, and I moved back and I pushed him away. I told him, ‘I’m only 16,’ and he goes, ‘Age doesn’t matter.’”

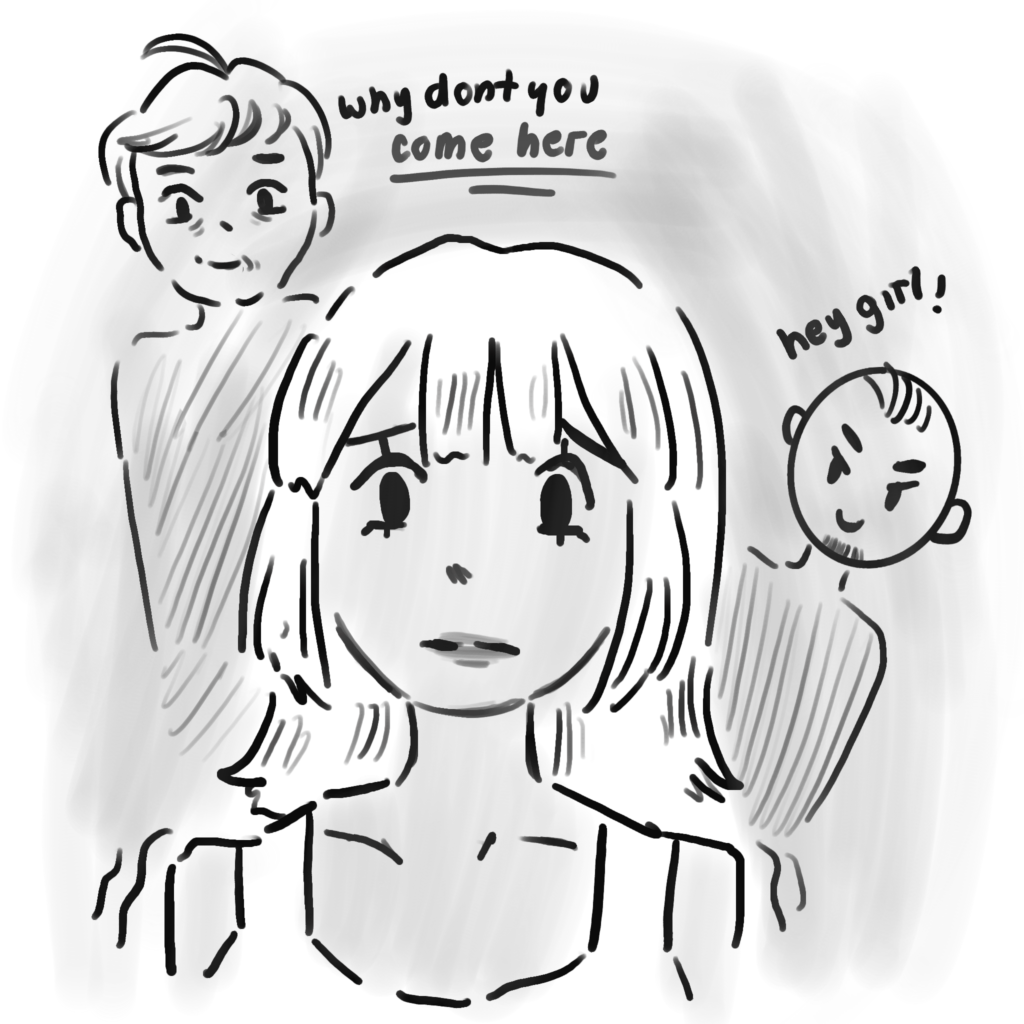

Unfortunately, frightening predatory encounters like Inez’s are all too common for teenagers. These instances, where predators, most commonly adults, manipulate, deceive and prey on teenagers, can occur anywhere, resulting in teenagers feeling uncomfortably alert and fearful of receiving unwanted sexual advances.

Just how common are these experiences? According to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, 56% of girls and 40% of boys between grades 7-12 have reported experiencing some form of sexual harassment. The emotional impacts of such harassment can be severe.

“It gave me goosebumps,” Inez said. “I just walked away and felt like I needed to throw up. I wanted to shed my skin and rid myself of that man. Creepy old guys coming at young women are disgusting.”

Senior Gaby Wang had a more local experience, as she was harassed while taking the Caltrain.

“I was just walking on the train on my phone, behind some guy,” Wang said. “He sat down and turned around, and he was like, ‘Hey, want to keep me company? I said, ‘No thanks,’ and he said, ‘Aw, sad face,’ … in this whiny, make-you-feel-bad tone.”

Predators often try to make their victims feel guilty for rejecting their advances so that they do not have to feel accountable for their victims’ discomfort.

“The assumption is that, of course, if he wants you to sit with him, you’re gonna sit with him,” Wang said. “If you don’t, … [you] should feel … ashamed because [you] just hurt this nice guy’s feelings, and now he’s all sad.”

There is a common misconception that predatory behavior occurs solely in public settings and from older men toward young women. But predation can happen to any gender, exist in any setting and can even come from one’s peers. Sometimes, jokes and playfulness from peers can be misconstrued as predation.

“Once I was at a party and … after, a girl I was hanging out with texted me and she said, ‘[If we ever got drunk together again would you kiss me or would you let me kiss you?]” said senior *Tristan. “That just doesn’t sit right with me. I think she was trying to say she liked me, but she didn’t know how to do it. It was miscommunication. I [also] could’ve said something better, but [it was a] heat-of-the-moment kind of thing.”

Predatory behavior can also occur online, where predators are able to easily lie about their identities to teenagers.

“People can put fake profiles and pretend to be a teenage girl to meet friends, and then it’s a creepy old guy,” Inez said. “It’s easy because you don’t know what they look like until you FaceTime them or see them in person.”

Rejecting predators or criticizing their behavior, for teenage girls in particular, can be incredibly dangerous, due to the possibility of violent retaliation.

“If you’ve jilted a dude, romantically [or] sexually, you could get killed,” Wang said. “That’s [something] that happens scarily often. Sometimes it feels like the easier thing to do is to smile and be nice and put up with it because … what he might do in retaliation if you say no might be worse. … So you’re always having to do the mental calculus and do the trade-off in your head, which is just a terrible thing to have to be doing all the time.”

Another danger of predation is the unbalanced power dynamic that can exist between the victim and the predator, who might be an older figure of authority.

“In my [former] school, there was this really creepy … teacher who looked down girls’ shirts and would touch girls in weird places,” said sophomore *Rachel. “[I signed] a petition [in which some] girls spoke up about similar experiences.”

When dynamics like these exist, it can be challenging and painful for victims to make their voices heard, out of fear of not being believed.

“It was very upsetting at the time for me,” Rachel said. “It’s still upsetting now. I always believe that you should believe the victim until proven otherwise.”

This raises the question: How can schools, and communities in general, make victims of sexual harassment and predation feel safe, seen and respected?

“I think having a club that’s aware of [sexual harassment] or having an assembly where people speak out about their stories and people can listen to them … would allow for students to be able to connect with each other,” said junior Katya Kleinhenz. “If someone starts talking about a difficult topic, it can inspire other people to also talk about it. … I always just get caught up in my own head like, ‘Well, I’m the only person who struggles with this, no one else is dealing with this.’ And when you hear other people it’s like, ‘Wow … we can help each other through this and get really angry about it together.’ … It definitely makes me feel less alone.”

Although sexual harassment is a severe issue amongst teens, many believe that if open conversations and education continue, more will be comfortable coming forth about their experiences, and predators will be held accountable for their actions.

“I think the issue will get better because I feel like the younger generations are learning more about equality and just being kinder in general,” Inez said. “There are more resources available for people who experience sexual harassment, and predators’ behavior is no longer tolerated in modern-day society. We have a long way to go, but I do see things getting better.”