Melody Liu

*This article contains sensitive content, including self-harm. Names have been changed to protect source privacy.

“I’m someone who grew up really skinny, really bony, really lanky,” said sophomore Rose*. “My weight was commented on so much … [and] I saw that as the one thing I had for myself — the one attractive thing about me, because I hated my face, I hated my hair, I hated my eyes, I hated my moles, I hated my skin. [I thought that] if I couldn’t change that, I can change one thing about me: I can change my body.”

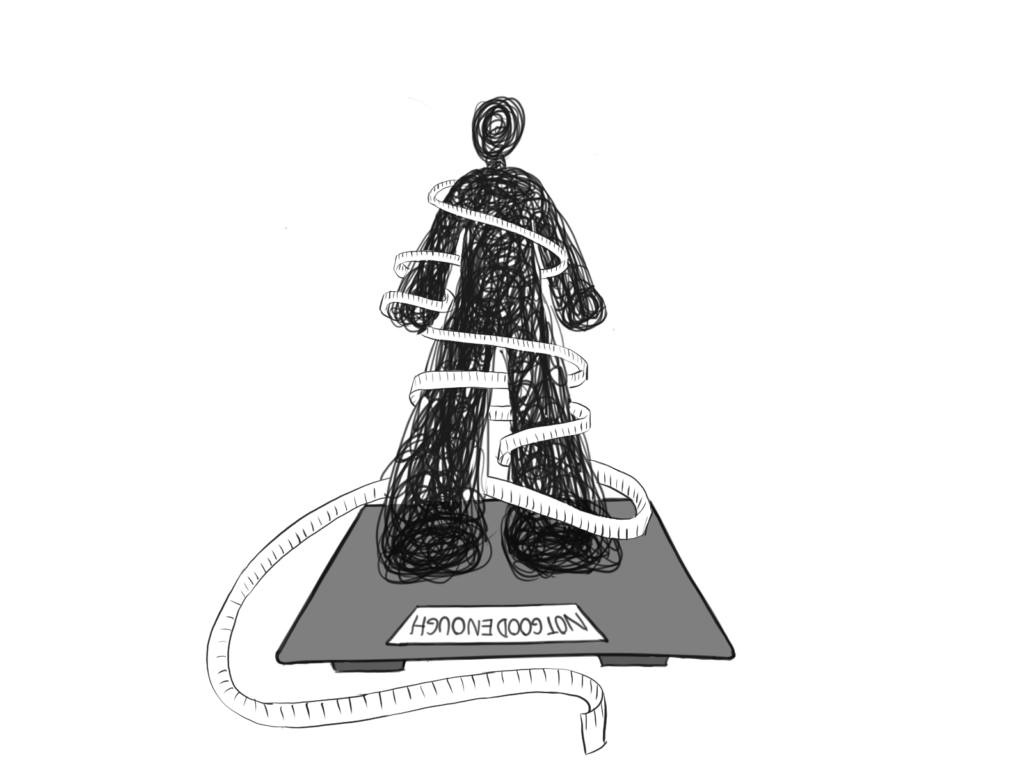

For Rose, like many others, her weight became her identity, a source of both validation and control. However, what may start as a desire to alter one’s body to reach supposed attractiveness can quickly spiral into something more dangerous: eating disorders. The term “eating disorder” is an umbrella term for a spectrum of psychological disorders characterized by abnormal or disturbed eating habits that can significantly impair one’s physical and mental health — the most common, according to the National Institutes of Health, being anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder and avoidant restrictive food intake disorder.

“It was, for me, a really [messed] up way to keep myself in check,” Rose said. “‘Oh, you weigh less than them. You’re better than them.’ It was the one thing I felt I had over everybody.”

Society, often through media portrayal, glorifies thinness and equates it with success and desirability, leaving some individuals with a sense of obligation to meet these unrealistic standards.

Causes

Eating disorders can emerge in childhood, often influenced by societal pressures and family dynamics.

“There was a lot of pressure from my parents to be relatively skinny [and] healthy because diabetes runs in my family, but it always seemed like that pressure to be thin wasn’t motivated by health but rather body image,” said sophomore Sasha*. “I was eight years old and I spent all of spring break … looking up different ways of how to lose weight [on the Internet] … I shouldn’t have known [about] that at such a young age, but I did.”

The effects of pressuring young children to care about body image can be detrimental.

“[When I was in treatment], one of the doctors that specializes in eating disorders said that … people should not be telling children to lose weight because it affects their growth,” said sophomore Mila*. “They should not be making us weigh ourselves in schools when there’s so much stigma around weight. … I hated that … We had clothes on and it was right after we ate. My weight there was higher than I’d seen it. [My PE teacher] decided to stare at it for the longest time … [It] made me self-conscious especially since there was another kid in the room … You can be … even healthier than the average person, but register as obese on the BMI scale.”

Individuals may receive harmful messages even from healthcare professionals, reinforcing the idea that weight is the sole indicator of physical health.

“My doctor told me I should start watching what I eat,” Mila said. “I was technically in the normal range, but she thought I was ‘too high’ [in that range], which doesn’t make sense. I was doing tennis every week … so it started becoming ‘let me prove you wrong. I can eat healthy.'”

The correlation between eating and health can be especially emphasized in athletic activities.

Athletics

In some activities, appearance becomes a measure of success.

“[My activity] is very aesthetic … and you have to be stick-thin,” said junior Jada*. “Being over [a certain weight] is considered obese … You’re in these skin-tight dresses in front of a whole bunch of people and [a] panel of judges judging you on how you look. That’s not a good environment to be [in], especially from a young age. Eating disorders are … normalized … If you don’t [have one], you’re kind of an outlier.”

The pursuit of performance can be misinterpreted as attaining a certain aesthetic. However, as junior Ian Ta found, success in sports goes beyond mere appearance.

“A lot of runners and athletes in general have the idea that being lighter is faster,” said junior Ian Ta. “Athletes at the Olympic level [are] super skinny, [but] there’s a difference between eating for performance and [for] aesthetics … If you want to fuel for performance, you might not look ‘as good’ … but you will feel much better and you will actually have energy every single day to practice. … [In the] summer of 2023, I started taking running super seriously so I started cutting back on calories, [but] I got super weak. I was injury-prone and I wasn’t able to run my best.”

Media

Stereotypes are often perpetuated by the media and popular culture, which predominantly portrays eating disorders as young, white women and girls engaging in extreme behaviors like self-induced vomiting or severe restriction. However, this narrow portrayal fails to represent the diverse spectrum of those affected by eating disorders.

“If it’s a skinny character, then [the media] displays it as anorexia,” said sophomore Anna Gubman. “If it’s a plus-size character, they [show] them binge-eating, but not showing that both of them can have both those [experiences]. It doesn’t matter what your body looks like. It’s all in your head.”

The media often oversimplifies the complex nature of eating disorders, strengthening public misconceptions and stigma.

“In the media, it’s portrayed as a problem, but at the same time it’s kind of glamorized,” Mila said. “[People] don’t see your hair falling out, your heart rate going down. My heart rate hit 36 [beats per minute] at some point. It’s supposed to be between 60-120. They don’t see how tired you get … You get dizzy when you stand up. I was walking up a [hill once] and I almost passed out.”

The depiction of eating disorders in the media has a significant impact on impressionable youth, potentially contributing to the development of such disorders.

“I [used to] watch those 2000s movies that would make really crude eating disorder jokes so I [grew] up with that mindset about it,” Rose said.

Stigma

Men in particular face unique challenges when it comes to body image and eating disorders.

“Often, [boys] get ignored because some of their behaviors include bulking and cutting [to gain muscle] … because they have a certain image people pressure them to look like,” said Carlmont sophomore Anila Ray. “[People] don’t acknowledge that that body standard is [also] really unhealthy.”

The stigma and lack of awareness surrounding eating disorders in males can prevent them from seeking help or receiving appropriate support.

“You don’t really hear about guys having eating disorders,” said junior Jorge*. ” I was hiding it because I didn’t think it was something guys had to deal with.”

The weight of the stigma surrounding eating disorders regardless of gender can often silence those who are struggling, especially when it comes to opening up to family members.

“My mom found out in the middle of seventh grade about [my eating disorder] and she was really mad about it,” Jorge said. “She felt that if I told her about it, she could’ve helped me.”

For many, the fear of disappointing their loved ones prevents them from seeking help.

“I wasn’t eating dinner and [my mom] said ‘we’re not doing eating disorders in this house,” Rose said. “She would always tell me that ‘bulimia rots your teeth’ and ‘you have to eat the food I buy you.’ It made me really scared to tell her that I [was] actually struggling [with] this because I didn’t want to disappoint her …. I was always too scared to say something to my parents. I was too scared to have confirmation that something was wrong with me. I’d read about [eating disorders] and think, ‘That kind of sounds like me, but I’m not fainting. I don’t feel light-headed. I’m just not eating breakfast anymore, but I’m not anorexic.’”

The fear of being labeled as having an eating disorder, combined with the belief that her experiences didn’t match the stereotypical image of anorexia, led Rose to doubt the validity of her own struggles.

“It made me not think I had [an eating disorder],” Rose said. “It still makes me doubt if I have one. I’d always feel guilty claiming it as my own or claiming to be a victim of it.”

Complexity

The intersection between eating disorders and other mental illnesses can pose significant challenges for those affected, often putting them at a disadvantage when it comes to seeking help and accessing appropriate treatment.

“Sometimes different disorders will feed off each other,” Mila said. “Eating disorders can sometimes develop because of other things, like depression or [for me] obsessive compulsive disorder… It’s an obsession around food, so [I] create [my] ‘food rules’ and follow [them to] an unhealthy level. … It was so hard [for me] … to get psychological treatment for both.”

Treating eating disorders is a multifaceted approach that extends far beyond addressing underlying mental health conditions alone.

“It’s a very complex disorder where you need a lot of players at hand,” said wellness counselor Jillian Ma. “You need nutritionists and [often] family therapy because you’re working on a system where everyone in the house needs to know what their part is in it. You’re working with maybe body dysmorphia or the anxiety of what food causes. It’s very much a multi-pronged approach [to] treatment … It’s just very important that it is done with a team of people who have the specific training [for] psychiatric, therapeutic, nutritional [and] medical [treatment] together because it can be very life-threatening.”

An eating disorder can manifest itself in the form of a cycle of unhealthy disordered eating behaviors, making it even more difficult to treat.

“I had this notebook where I was counting the calories in my food, what I was eating, and the set limit I had for myself of what I could and couldn’t eat,” Jada said. “But then it got so stressful to the point [that] I started binge eating … because I got so stressed from restricting myself. Then I’d feel super guilty which is why I would throw it all up.”

External pressure on body image can also fuel these destructive cycles.

“Comments [from other people] implied that I had to lose weight to look attractive so I would just not eat for long periods of time and then I would end up binge-eating,” said freshman Chelsea*. “I would make myself throw up after to avoid the guilt. That was a cycle [and it] happened a lot when I was stressed about something or some comment was made about me.”

Language

The language used to describe eating disorder behaviors can also glamorize or minimize the severity of eating disorders, like model Kate Moss’s infamous “Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels!” or “Once on the lips, forever on the hips.” Terms like “clean eating,” “cheat meal,” or “thinspiration” may seem harmless, but they can reinforce unhealthy attitudes towards food and body image.

“We’ve just accepted ‘oh, I’ve eaten too much today,” Rose said. “Language like that is kind of normal. Whenever I hear my friends say that, it’s kind of worrying to me because I recognize it [as] what I used to say when I was struggling … We can have better language around [our] bodies. People commenting on how much food someone’s eating or on how other people’s bodies look doesn’t help.”

The term “eating disorder” itself can contribute to misunderstandings, with some preferring the term “disordered eating.”

“It’s a small nuance [but] you don’t want to necessarily define a person as a disorder,” Ma said. “It’s something you experience, not something you are.”

Education

Eating disorders are complex mental health conditions influenced by a myriad of factors. Being educated and aware of the harmful nature of eating disorders may not protect someone from developing one.

“I remember we learned about [eating disorders] and I thought, ‘Why would people do that?’ Mila said. “’I don’t understand how that works.’ I thought I was the most body-positive person ever, that I was never going to get an eating disorder because I knew better … I didn’t think I could develop an eating disorder bad enough to need help because I thought I knew when to stop. I thought I was so educated about it that it wouldn’t be a problem for me, that I’d be able to avoid [the consequences].”

Even when presented with the opportunity, some may be reluctant to learn more.

“[In health class] when they’d be like ‘you can do these anonymous questions,’ I was always scared someone would see me writing it… so I just never asked for help,” Rose said. “I really isolated myself… because I was paranoid about everything.”

Resources

Despite having access to help, the need for control can cause people to ignore them.

“We’re privileged,” Sasha said. “We have a roof over our head. We’re given food, we’re given resources, and we have a community to support us, but I was cutting those things out of my life. I wasn’t letting people give me the help I so desperately needed because I wanted to be in control. I was miserable, but at least I had control.”

Some go to extreme measures to hide their eating disorder, underscoring the need for professional treatment.

“When people realize their friends or someone they care about has an eating disorder, they try to force them to eat,” Mila said. “It’s not going to work. You need a professional for that because it’s really easy for us to hide. In school, you’d think my eating habits were normal. At dinner, you’d think my eating habits were normal.”

Ray, an ambassador to the nonprofit organization Project HEAL which focuses on expanding access to treatment for eating disorders, believes more education is needed on the subject.

“It’s hard to know when you’re bad enough to need help,” Ray said. “People have this image of you having to be skinny, underweight, dying, but you don’t. It’s a mental state.”

Such ideas can make it difficult for people to find help.

“Eating disorder hotlines aren’t advertised or displayed as much because people are scared to talk about it because it’s tricky to deal with [and] it’s different for everybody,” Gubman said. “I don’t think help is shown as much as it should [at Aragon].”

However, support and resources are available at Aragon.

“Any trusted adult on campus can at least get [a] student [with an eating disorder] to the right person eventually,” Ma said. “The ‘caring adult’ piece is what we hope … can gear the student [toward] the help they need, versus Aragon doing something hands-on.”

According to Ma, the process begins with speaking to the student’s family and encouraging them to take them to their primary care physician. The wellness team can also connect students with the Stanford Medicine Children’s Health Teen Van, which offers free health services to students without health insurance, and Care Solace, which connects students with mental health services.

Despite having support systems in place, the desire for control can overshadow the need for help.

Ultimately, eating disorders are extremely complex and there are various factors that contribute to their development and persistence. The stigma surrounding eating disorders, through internalized beliefs and societal expectations, can prevent individuals from recognizing their struggles and seeking help. Eating disorders are not simply about food and weight but are deeply interlinked with emotional and psychological struggles.