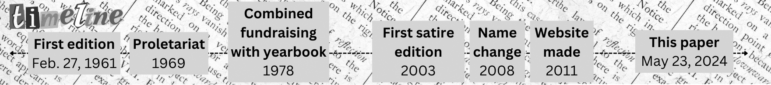

Three question marks emblazon the front page, beckoning the student body to vote on a name. On Feb. 27, 1961, students from Aragon’s first graduating class published the first issue of their student newspaper. The next issue announced itself as “The Aristocrat,” defeating “The Aragonian” by 26 votes. The name remained until 2008, until The Outlook was voted in by the student body.

“We had several meetings and names were tossed about as far as what [the newspaper] should be called, what it should look like, who would be on it [and] how would we divide it up,” said 1963 editor-in-chief Sherry Garcia. “So it was quite an adventure to start something from the ground up.”

Aragon’s student newspaper has lived through several defining eras of American history. Rising tensions in the ’60s produced protest movements against the Vietnam War and racial segregation, all under the shadow of the Cold War. Contrasting opinions on such global and national conflicts were prevalent at Aragon when an underground newsletter, The Proletariat, surfaced in 1969, contrasting the elite Aristocrat.

“It was a period of ardent, strident activism,” said Chris Hyink, the brother of The Proletariat’s founder Lawrence Hyink. “It brought about a number of actions, and one of those actions was a newsletter. The Proletariat was a way of putting a voice on campus that wouldn’t otherwise have been heard. The Aristocrat … was not a vehicle that was allowed to be too controversial … They’re not going to let you call for a student strike. They’re not going to let you … organize rallies or [express] any kind of dissent to the status quo.”

Some students felt that The Proletariat reflected their opinions more accurately. The newsletter was published every few months, while the Aristocrat followed monthly cycles.

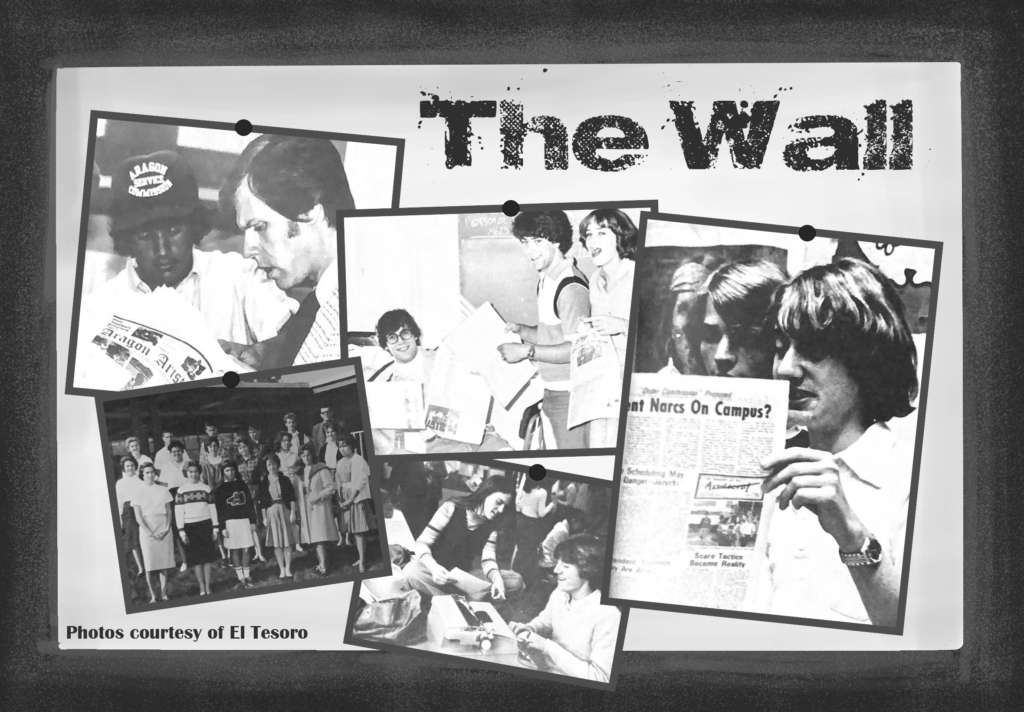

“There was what was called ‘The Wall’ [at Aragon, located between the two gyms today,] at the time when the Berlin Wall was a symbol of resistance,” said former Aragon history teacher Peter Lawrence. “And [on it] students were posting their work — editorials, opinion pieces, cartoons, all sorts of things about the world, particularly the Vietnam War. And that is where the Proletariat was posted.”

Copies of the underground newsletter would also appear on library tables, planters around Center Court and other places around campus. Students, however, had mixed reactions to the newsletter.

“There were some who would tear it down [from the wall] as soon as they saw it and others who would then defend the right to post it,” Lawrence said. “I [felt] very strongly about freedom of speech and press. I wouldn’t tear it down. I was sad … that [it] was seen as necessary by somebody [who] couldn’t feel comfortable enough to utilize the existing structure to voice their opinion.”

Hyink recalls the process of his brother, Lawrence Hyink, creating the newsletter.

“The house was filled with … periodicals and what we talked about were the politics, and [its] depths and layers,” Hyink said. “Every day was peeling onions in terms of what was going on in the political dynamic … Larry [is] prolific in his writing. He’s a very smart guy. And he has a very clear vision and outlook. There was [a] lot to protest then so it was easy to draw on subject matter.”

A major change occurred on June 6, 1978, when California voters overwhelmingly passed Proposition 13. This amended the state constitution and shrank the income of high school districts across the state by limiting state property taxes. Student-teacher ratios soon increased and the performance of public school students in California fell rapidly relative to other states.

“It was a very, very difficult time, [because] from 1978 the principal had very little discretionary funding to provide the newspaper,” said Philip Fisher, the Aristocrat’s adviser from 1980 to 1986, and former English teacher. “So the newspaper began to die … The principal called me in and said, ‘Phil, I’d like you to take control of the newspaper.’”

Although initially hesitant, Fisher decided to partner with then-business teacher Donald Tingley, who was previously an editor of the San Mateo High School newspaper, to advise the yearbook and the newspaper.

In the summer of 1980, Fisher came up with the idea to create a package with the yearbook, newspaper and student body ID card in order to increase revenue for the newspaper.

“The orders begin to roll in and we now have enough money to run the newspaper,” Fisher said. “We [decided we] would send the newspaper by mail to everyone for the first [cycle] to make that well-known.”

Between thte 1980s and the early 2000s, the paper had to adapt to the new technological advancements, which could be utilized for a more efficient process.

“By the time that I was [an] editor, we had started transitioning to …[a] more digital way of making the newspaper,” said 2003 graphics editor Der-Shing Helmer. “It [used to be] more hands-on, more physical, and we were transitioning at the time to try to make the newspaper more computer-based.”

With the transition, more and more technological problems started to arise, leading to the creation of the role of technology editor in year.

“I was brought on as a tech editor to assist with computer-related problems that happened during deadline nights,” said the first technology editor, Stephen Moss. “And generally throughout the course of the year, when something was wrong with the computers I would be able to fix it expeditiously so that nothing would be delayed or held up.”

In 2008, issues were raised over the name The Aristocrat, and current history teacher Scott Silton, who took on the role of journalism adviser in 2003, decided it was time to propose a change.

“In those first few years as adviser, I started going to the professional development … workshops and whatnot,” Silton said. “We’d all introduce ourselves, and [there] were definitely weird looks [and] questions about ‘The Aristocrat.’ I was coming from a less privileged school and community [before Aragon] and … it felt a little awkward to be The Aristocrat.”

Silton and the editors at the time decided to have a discussion and vote on whether they should proceed with changing the name. Emma Citrin, the editor-in-chief at the time, pushed for the name change the most.

“It was a conversation that had been happening for a long time, but I think we decided, let’s take the lead,” Citrin said. “We know that the newspaper itself [has] quality and the names not going to change the substance … and standard that we held ourselves to regarding what we’re putting out … It’s just a little bit more inclusive.”

Mirroring the 1961 editorial team’s actions, the 2008 editors decided to take a schoolwide vote with three alternative name choices, including “La Fuente,” “The Verity” and “The Aragon Outlook.” With more than 1500 ballots submitted, “The Aragon Outlook” won the vote, and has remained since.

“Something that I personally enjoy about the Outlook … is that it only gets better [over time],” said current editor-in-chief Aakanksha Sinha. “It is our tendency as journalists and as human beings to take what we’re given and find a way to improve it. And when you look at it in the long term it’s this holistic, amazing growth, like look at the stuff we publish this year versus the kind of stuff we published years ago. There’s just so much progress that way.”