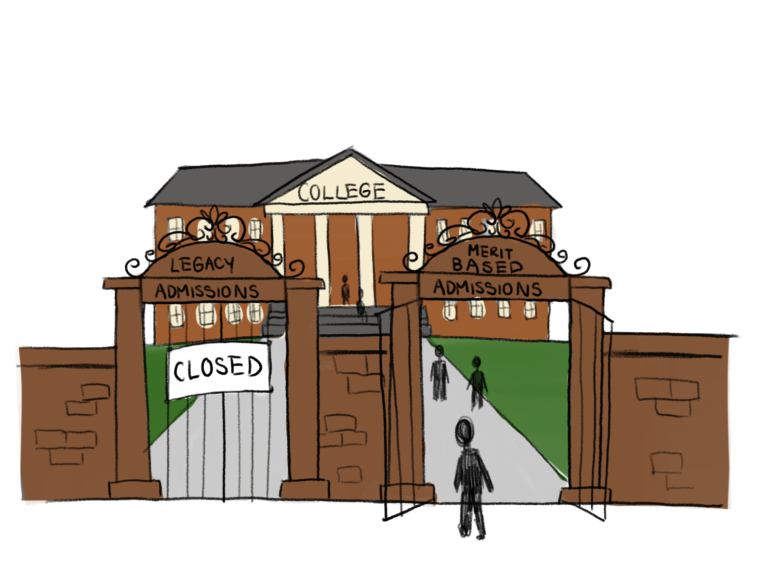

On Sept. 30, Gov. Gavin Newsom passed a law banning private colleges and universities in California from practicing legacy admissions and giving an advantage to applicants with donor connections.

Legacy admissions refer to the preferential treatment of applicants who have a relative who is an alumnus of the institution. The practice began in the early 1900s as a way to limit the amount of students from marginalized communities in higher education. California is the fifth state to implement a ban on legacy admissions, and the second to do so for private institutions. The University of California schools stopped considering legacy status in 1998.

Colleges will have to make an annual report to the California Department of Justice, stating whether or not they complied with the law. The names of the schools that violate the law will be posted on the DOJ website.

“In California, everyone should be able to get ahead through merit, skill and hard work,” Newsom said in a statement released by his office. “The California Dream shouldn’t be accessible to just a lucky few, which is why we’re opening the door to higher education wide enough for everyone, fairly.”

Some students agreed with the law.

“The opportunity for education should not be limited to people with more financially well-off backgrounds,” said sophomore Nate Wilson. “The opportunity for a good education, where you want to study, should be given to anybody, equally, regardless of background.”

Others, however, felt differently. Sophomore Marina Wiedmann reflected on her reaction to hearing about the new law.

“I’m a bit disappointed because I have a ton of Stanford legacy,” Wiedmann said. “My whole extended family, other than my dad, went to Stanford … so I would have had benefits.”

Wiedmann’s response aligns with that of other students who will no longer be able to utilize connections to alumni.

“One of my friend’s parents went to Stanford, and she was caught off guard [by the ban],” Makuta said. “She thought it might’ve been easier [with legacy], and now she realizes that if she truly wants to get into Stanford, she can’t have a fallback plan of her parents’ legacy. [This law] spurs people to work harder.”

Senior Sora Kim-Steiger, who is planning to apply to a school where she has legacy, explained that for those with donor or legacy connections, it can be appealing to use that advantage.

“Colleges now have gotten so, so competitive,” Kim-Steiger said. “Having legacy increases your chances [of getting accepted] … it is kind of a booster to help you get into a college. In the end, most people just want to get into a college.”

Other students with legacy had different perspectives.

“Inherently, [legacy is] unfair,” said senior Marcus Finke. “That’s not going to stop me from [applying to schools with legacy] right now, but I don’t think it’s the best way of determining who should get in.”

Students spoke about the overall impact of ending legacy admissions and donor preferences.

“It’s not going to completely level the playing field, because obviously if you’re in a more wealthy area, you’re going to have better access to resources that help you succeed, versus if you’re an underserved area, it’s going to be harder to do as well in general,” Wiedmann said. “So although it levels it somewhat, it’s not black and white [fixing] the problem.”

Mary O’Reilly, Aragon’s college and career advisor, commented on the significance of the ban on college admissions.

“There’s a lot behind getting into these schools,” O’Reilly said. “Making sure that supports are equitable for students … will be a big factor. I don’t think [the ban] will make a grand impact. It might be a step in the right direction, but [there are] other follow-up things that need to happen as well, [like] equitable services for students.”

Many agreed that there is still more to be done to fully eliminate inequity in the admissions process.

“Despite the fact that we are in the modern age, we’re still separated a lot by class, race and identity,” Makuta said. “Banning legacy admissions [is] just one step into becoming equal.”

The law will go into effect in the fall of 2025 and will affect the graduating class of 2026.