Ian Wang

“I never meant to hurt you,” they say—moments after the outburst, the shove, the insult. The apology feels hollow, a repeated cycle that never seems to end. For many, it is a pattern they’ve come to expect: the brief bursts of tenderness followed by more hurt.

However, this behavior does not stem from a simple desire to hurt. At its core, abuse comes from a need for power: an insecurity twisted into dominance, where love is replaced by fear and control.

“I believe that it is more often people trying to exert power to maintain some sense of control when life leaves them feeling without control,” said wellness counselor Max Bernstein.

When someone feels out of control at work, in their social circle, or in other personal circumstances, they may seek to regain that power through their partner. It is a way to feel a sense of authority in an environment where they otherwise feel weak or diminished.

For some, this need for control stems from deeper psychological issues, such as unresolved trauma or learned behaviors from childhood.

“[My abuser] would always talk about his dad and how strict he was with his mom — always telling her what to do, who she could talk to,” said senior Riley*. “He would always say ‘my dad was tough on my mom, but it’s because he loved her. If you love someone, you keep them in line.’ He thought that was just how it’s supposed to be. After a while, I [also] thought that [was] how relationships work.”

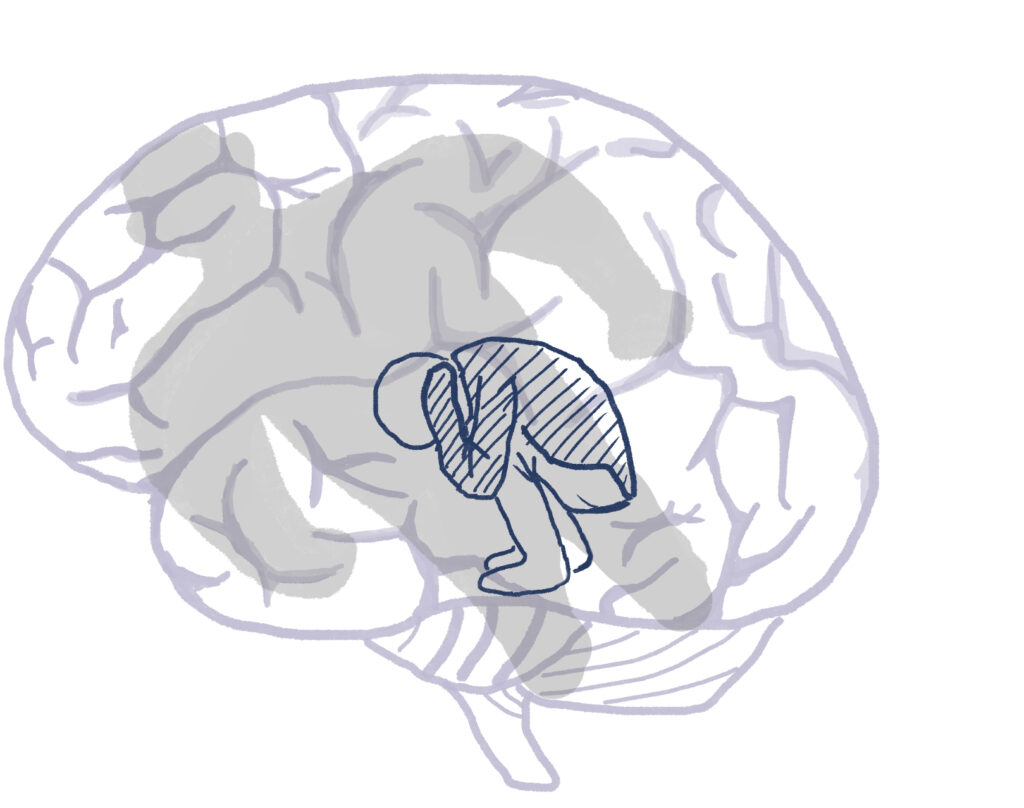

This doesn’t excuse abusive behavior, but it sheds light on the underlying causes of these actions. According to Dr. John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory, the bonds children make with their caregivers are important for emotional and social growth. His colleague, Mary Ainsworth, identified different attachment styles — secure, avoidant, and anxious — developed in adolescence.

These attachment styles can affect behavior in relationships, particularly unhealthy ones. For example, someone with an anxious attachment style may act jealous or possessive due to a fear of abandonment. Those with disorganized attachment may swing between being overly loving and distant, creating a cycle of destructive behavior.

A person trapped in this harmful mindset, influenced by past attachment experiences, may struggle to recognize or change their damaging behavior.

“[My abuser] was so deep into this mindset that [this behavior] was normal that he wouldn’t have changed,” Riley said.

Similarly, abusers may not simply be aware of the negative consequences of their actions. Cognitive dissonance, a psychological phenomenon where there is a disconnect between what someone believes and how they behave, often plays a role. An abuser may see themselves as loving, yet their controlling or harmful actions contradict that belief. To ease the discomfort, they justify their behavior, reconciling the conflict and perpetuating the cycle of abuse.

“[My abuser] honestly believed that … if you really cared [about the other person], you had to keep them close, make sure they didn’t stray, keep them in check,” Riley said. “He’d be like ‘I’m just protecting you because I care so much.’ But it wasn’t protecting me, it was keeping me locked down, so I wouldn’t go anywhere.”

Nevertheless, even if there is some level of awareness on the abuser’s part, it may not translate into meaningful change. The difficulty of acknowledging one’s own abusive behaviors involves an immense amount of introspection and self-criticism, which many perpetrators simply aren’t willing to do.

“Even if [my abuser] did realize it, I don’t think he would’ve wanted to change,” Riley said. “It would’ve taken a lot of work, and he [was not] willing to really look at himself like that.”

The broader cultural context around abuse has historically played a significant role in enabling and protecting abusers. Power structures in industries like entertainment, politics, and corporate environments often create the perfect storm for abuse to thrive.

When one person holds significant authority, it can lead to a dangerous imbalance in which individuals are vulnerable to manipulation, coercion, and even assault. Abusers, leveraging their power and control, can exploit this dynamic, knowing that their victims have little recourse due to the fear of losing their careers, credibility or social standing.

In the mid-1990s, actress Gwyneth Paltrow was allegedly sexually harassed by film producer Harvey Weinstein. However, she only publicly accused him when the #MeToo movement gained traction over 20 years later in 2017.

Weinstein’s behavior reflects how men in positions of power can exploit their authority to demand sexual favors in exchange for professional advancement, and women may be too afraid to speak out because of the fear of professional ruin.

Women are frequently viewed as less credible or more emotional when speaking out about abuse, despite an ABS 2016 Personal Safety Survey that found that women were eight times more likely to experience sexual violence by a partner than men.

These disparities are often perpetuated by traditional gender roles in a heteronormative society, where women are viewed as more submissive, emotional or deferential, reinforcing a power imbalance that makes abuse more likely to occur.

“I’ve spoken to students and encountered a sense that there are nothing else but gender roles we fall into and assumptions that certain people should be more deferential, which sets up a different power dynamic,” Bernstein said. “In that sense, one person is supposed to be more deferential and therefore someone else is demanding that deference.”

This expectation of submission creates an environment where control and manipulation, as Riley experienced with her abuser, become normalized.

“[My abuser] thought girls should just follow a guy’s lead,” Riley said. “If I hung out with a guy friend or wore something he didn’t like, he would say ‘that’s not what a girlfriend should act like.’ It wasn’t about me as a person, it was more like I was his to control.”

However, efforts to encourage change, particularly through restorative justice, provide pathways for offenders to confront their behavior and the harm caused.

“There’s a tremendous amount of shame attached,” Bernstein said. “There is a lot of thought and attention from the restorative justice perspective to have the perpetrator understand the impact of their actions to help create the openness and the possibility for change … At the very least, ‘gaslighting’ [being] a common term allows people to look at behaviors and interactions and start calling attention to them so that potential perpetrators can become more aware of their actions rather than reenacting the norms.”