“That skinny, blonde, white archetype that’s always described as the pinnacle of beauty makes me mad,” said junior *Sally. “I [thought] if I didn’t fit that, I’m not really beautiful no matter what I look like.”

This intense frustration reflects the core of body dysmorphia — when a person becomes obsessively fixated on an idealized standard of beauty, often feeling that they don’t measure up.

Body dysmorphia, or Body Dysmorphic Disorder, is a psychological condition where a person becomes obsessively preoccupied with perceived flaws in their appearance. These flaws, whether they involve skin, hair or other physical features, are often exaggerated or completely imaginary.

For many, body dysmorphia begins with external pressures. The constant scrutiny and pressure to meet certain body ideals can lead to the development of distorted perceptions about one’s physical appearance.

“I play multiple sports where the majority of your body is exposed for everyone to see,” said student *Randy. “You can’t throw on a jersey. Everyone sees your body. The thought of that makes you want to look good in front of everybody.”

For Randy, this pressure was particularly intense as an athlete.

“When you think of a swimmer, you think of someone tall, toned and lean,” Randy said. “I didn’t fit that description … For example, Michael Phelps is tall. He has a long wingspan. He’s very skinny but he’s very muscular as well … I didn’t look like [him]. I thought it was a bad thing, so I really tried to change my body so I could look like him.”

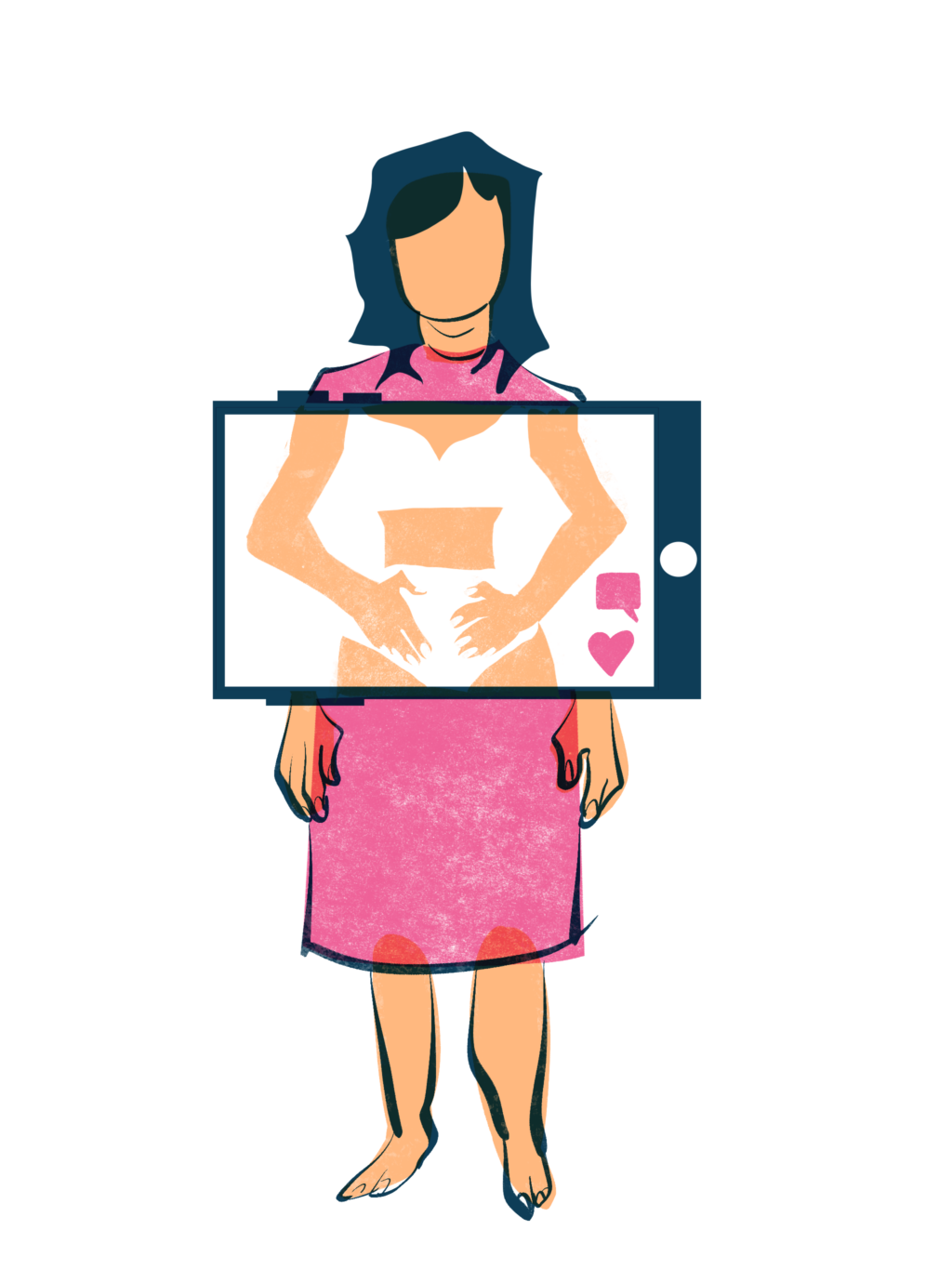

This pressure to conform to a specific body type is amplified by social media, where influencers often portray idealized versions of themselves. In fact, many even use social media as a means for validation, feeding their body dysmorphia.

“[Social media] brings up all these different terms for insecurities that literally don’t exist and it’s insane,” Sally said. “The gua sha stuff, ‘use these supplements, use this waist trainer.'”

The constant exposure to these “perfect” images encourages comparisons, making people feel inadequate when they don’t fit these ideals. This fixation on perceived flaws can lead to unhealthy behaviors like excessive grooming, mirror-checking and skin-picking, among others.

“I have a birthmark on my left arm and in elementary school, I would only raise my right arm because no one else had a birthmark,” Randy said. “I didn’t hate it. I just thought ‘oh, my God. I have a birthmark. I’m a freak.’”

While these behaviors developed early in life, Randy’s struggles continued into his teenage years.

“Mentally, it was really hard to look in the mirror after I showered or after practice,” Randy said. “I often eat [unhealthy] food and I think ‘why am I eating all this? I shouldn’t’ … Some days, I wouldn’t eat that much to make up for that.”

This cycle of overeating and restricting is common among those with body dysmorphia and can contribute to the development of eating disorders, further exacerbating the physical and mental effects of the disorder.

The emotional confusion that accompanies these struggles is often hard to express or even understand.

“It made me feel like I was crazy,” Sally said. “No matter how I looked, it wasn’t good enough. [Sometimes], I thought I was skinny, but then I’d have stomach rolls when I sat down that made me think I was fat.”

The challenge of verbalizing these experiences often leaves those with body dysmorphia feeling isolated.

“When you try to vocalize it, people just tell you ‘no, you’re crazy. What are you talking about?’” Sally said.

Fostering empathy and understanding for those affected by body dysmorphia, offering support instead of judgment, can help create an environment where individuals feel safe in questioning harmful beauty standards and ultimately move toward self-acceptance.