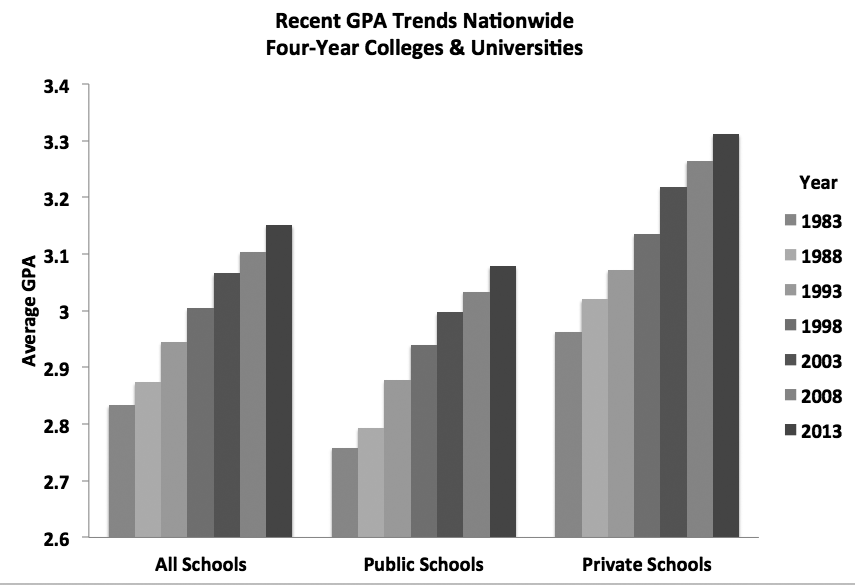

In today’s educational landscape, the idea that “everyone’s a winner” has become more than just a motivational slogan; it’s slowly, but surely, permeated into the grading system itself. As teachers seek to avoid discouraging students, grade inflation has become a widespread practice where students are given the same grades for less rigorous work. According to Stuart Rojstaczer, who wrote an op-ed piece about grade inflation for the Washington Post, grades surged in America during the 1970s and once again in recent years, even more so during the pandemic.

To truly understand what’s so harmful about this, the causes of grade inflation must first be examined. Schools, particularly competitive ones, are pressured to maintain high academic standards and positive reputations. The attending students are similarly very career-oriented and reach for high grades. This puts teachers in a difficult position, as they may face pressure from students and parents to inflate grades.

“Sometimes, it feels hard to give a student a grade they deserve when they expect something else,” said Pre-Calculus and Advanced Placement Calculus teacher Cheri Dartnell. “It’s a constant battle of maintaining your standard regardless of the tears and pressure that come from students and parents for high grades. I have observed, ‘I didn’t do as well as I wanted to on the last test, is there extra credit?’”

Schools are also shifting towards more holistic teaching approaches that emphasize collaboration and creativity. While this on its own is a step towards a better educational future, the traditional grading system struggles to reflect these shifts. As a result, grade inflation emerges as the convenient, though flawed, workaround.

Despite well-meaning intentions, grade inflation carries severe consequences. For one, high grades become much more average. When students receive higher and higher grades, it becomes harder to discern who truly excels. The distribution of grades becomes more clustered at the higher end, and lower grades stick out much more, becoming even more devastating. When the average is pushed so high, anything below that can feel like a major failure. This pressure can also have a negative impact on mental health.

Although grades are rising, true mastery of curriculum doesn’t seem to be. According to the 2019 National Assessment Educational Progress High School Transcript Study, although the grade point average increased from 3.00 in 2009 to 3.11 in 2019, the mathematics assessment score decreased. A similar 2021 study on ACT data by Edgar. Sanchez showed that despite average ACT Composite scores declining to its lowest in the past decade, test takers have received more A grades and less B grades over time.

Grades and tests are meant to measure students’ abilities, but with grade inflation, they fail to do so accurately. This can give students a false sense of accomplishment, undermining the true purpose of education. They may spend less effort to truly understand the material and be satisfied with an easily gained, shiny A rather than be more motivated to pursue harder classes.

In today’s competitive college application process, high grades and AP courses are often seen as essential for getting into prestigious schools. However, due to grade inflation, a good high school transcript now may not actually represent a students’ true capabilities, possibly leaving them unprepared for the academic rigors awaiting them in college.

“If we bend to every student that wants extra credit to get the A’s, and they’re not showing mastery of material and they get into X-school, will they be successful?” Dartnell said. “Is that actually the right fit? You might be a big fish in our little pond, but when you get to that X-school, you’re a tiny fish. That may not be the right fit for you if you have been, ‘Can I please do extra credit? Can I please retake that test’ … All of it makes a package that maybe gets you in somewhere that is not a right fit.”

Some people may argue that grade inflation helps alleviate inequalities in the school grading system, particularly between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds. In one way, it might act like an equalizing force and give everyone a fairer shot at success. However, according to the Atlantic, “students whose parents had the lowest levels of education experienced the least grade inflation.”

Although taking a more holistic approach to education where learning and individuality are top priority is a step in the right direction, inflating grades can unintentionally diminish the value of academic achievement.