Reporting by Diya Poojary and Zack Li

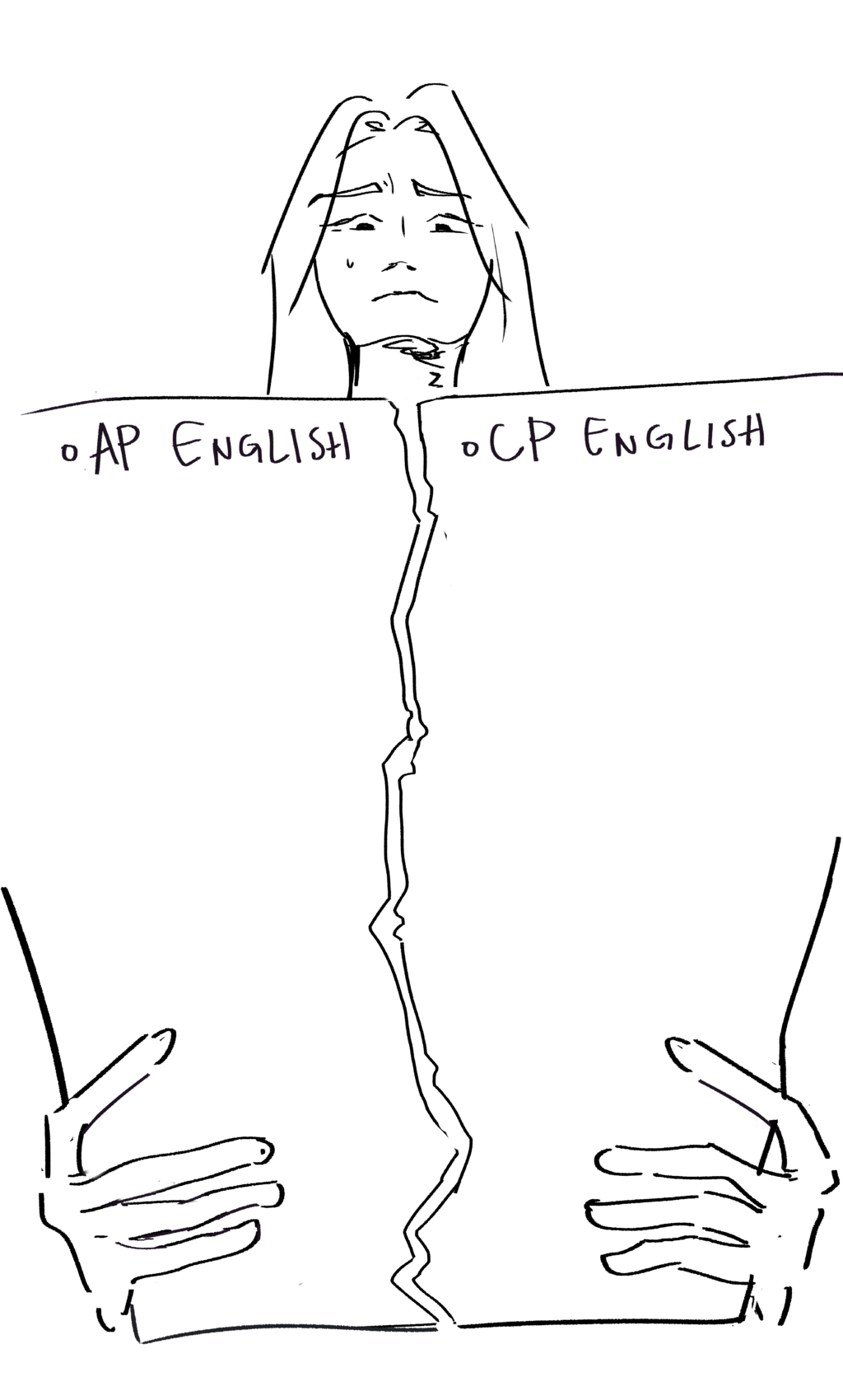

It’s difficult to find labels shorter than the two-letter AP and CP bubbles on the course selection sheets that have made their annual wave through the hands of Aragon students.

Yet, these labels, representing Advanced Placement and College Preparation respectively, go beyond class schedules and perpetuate a social divide between AP and CP students — especially considering that Aragon offers 19 AP classes, twice the number the average high school offers.

“Students that have taken [Advanced Standing] classes … have been together for a couple of years [and] by the time they get to AP, they’re a nice little family unit,” said counselor Lea Sanguinetti. “[But] sometimes students, if they’ve never taken an AS class, but [choose] an AP … feel like students in the class don’t pay them any attention, don’t want to get to know them. When I hear from [those] students, it makes me believe that there is that divide out there that students are creating.”

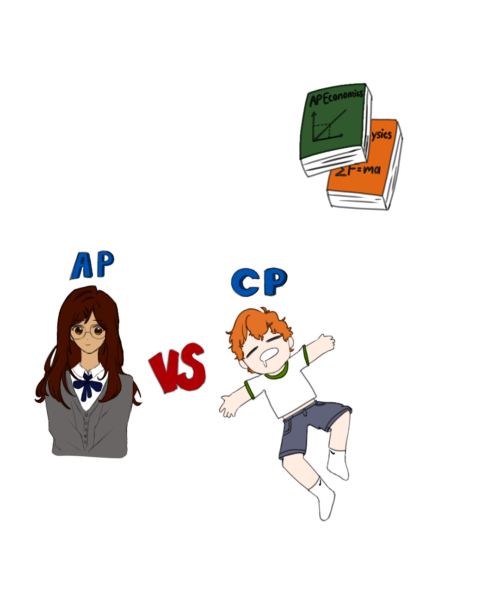

But familiarity with peers, or lack thereof, is only one cause of the divide. Others argue that the difference in academic rigor creates a preconceived assumption of what kind of person a CP or AP student should be. The choice to take an optional, more advanced class forces students to mold themselves into what best fits restrictive stereotypes of taking the “normal people” or “smart people” courses.

“People perceive people who take mostly APs as being more studious,” said senior Samarth Hegde. “Sometimes, even I fall into that tribe and when someone’s telling me, ‘I don’t take any APs,’ it’s just that thing in my brain [that’s] like, ‘oh, maybe they’re not as studious’ … sometimes you unconsciously do it.”

The divide may also be caused by academic pressure. Aragon’s many alternative pathways and courses, especially in math, science and career technical education contribute to its reputation as an academically competitive school.

Counselors often observe that students stack their schedule with the sole goal of putting together an ambitious college application. Many students also take up summer courses to accelerate once they enter high school, even if it may not align with their interests.

“What’s the drive to do that?” Sanguinetti said. “A lot of the time [students] can’t answer that question. ‘Oh, my mom or my dad want me to take that’ or ‘oh, I have 10 friends that are doing that’ … it’s that fear of missing out again … all of a sudden everybody’s running [in] that direction … There’s not a real reason [for] why that student wants to accelerate.”

Meanwhile, students rushing to take AP classes retain a flawed label of what CP classes are, which only serves to perpetuate the notion that taking more advanced classes makes one superior to others.

“I was talking to one of my friends [about] how Algebra 2 is really rough for me and [she] started comparing me to her, [saying] ‘but you’ve never tried AP [Statistics]. AP Stats is so much harder,’” said junior Heli Artola. “And just being like, ‘oh, you might be in that class, but I’m in a higher level. I’m more academically well, it’s so much harder up here’ just [made me think] we really do only care about what academic status people are [at].”

This mindset propagates a culture of academic elitism at Aragon, one that promotes academic exclusivity and the dismissal of struggles faced by students who cannot keep up with the rising and unrealistic academic expectations at Aragon.

“Even though I’m taking so many [hard] classes … I still feel like I’m not as smart as everybody else,” Artola said. “Because … if I turn around and ask somebody, they’re taking more … it definitely makes me feel lesser than I am because I’m struggling so much with what I’m doing.”

“Grades are a big part of Aragon compared to some other schools,” said freshman Emilia Matye. “So when I’m talking to friends about tests or something, everyone’s really concerned about what I got on the test or what my grades are because that’s just the standard here. Everyone wants … to be better and that’s a good thing but it can be a lot of pressure … it worries me when I don’t get good grades because I know there are many other people who are like, ‘oh no, I got a B.’”

These generalizations, often obvious to the receiving end of students, foster insecurities when they begin to compare their academic lives to students in more advanced classes.

“Even though I’m taking so many [hard] classes … I still feel like I’m not as smart as everybody else,” Artola said. “Because … if I turn around and ask somebody, they’re taking more … it definitely makes me feel lesser than I am because I’m struggling so much with what I’m doing.”

Some students also take these classes because their friends are doing so, contributing to the divide because their social circles become stagnant and they interact with the same people every day.

“I have a good gauge of when a student comes in and it’s a true passion … but where the problem lies is that person’s five friends, who feel like they’re missing out,” Sanguinetti said. “And that’s not what it needs to be about, because that person’s friend might really shine in physics or science or the arts or band or drama.”

Taking classes solely to accumulate credit despite having no interest in them could also lead to an unhealthy internal mindset.

“Sometimes I don’t have interest [in] the things I’m doing, I’m doing it just because I can,” said freshman Rui Liu. “Then it would get too hard to the point that I don’t want to learn it anymore, it would be too complicated for me to understand, and by then it would be very easy for me to give up … And eventually I’d be like, ‘why did I do this at all? I just wasted so much of my time, and I never actually got the wanted result.’”

However, not all students feel this pressure to take hard classes.

“The level that all these classes [I’m taking] are good for me,” said sophomore Orli Riter. “I’m already very motivated and I know what I want to do for the future, so I don’t think it’s going to sway me much.”

Of course, the divide is not a black-and-white issue. While having classes together certainly makes friendships stronger, community can also be found elsewhere, such as in extracurriculars or clubs.

“At the end of day, it’s just a class,” Hegde said. “You might sometimes talk to people from that class more but it doesn’t mean you’re going to suddenly only have friends that are in APs. You’re still going to have that old friend group and structure in other classes.”

Ultimately, the divide between AP and CP classes reflects a broader issue of perceived academic status tied to course rigor. While these classes may help to cater to different academic goals, students can also acknowledge communities beyond academics.